Jamie Jelinski’s Needle Work begins with a peculiar introduction: the story of Edgar Fournier, a Progressive Conservative senator from New Brunswick. The Senator’s story has nothing to do with legislation or laws. No. This is about a Last Supper scene tattooed across a man’s back, a tattoo inked by Fournier himself. This story also features a Senate messenger named Roger Lalonde, who described tattooing as a hobby for most of his life and tattooed for profit before his role in the Senate. Published initially in the Toronto Daily Star in July 1969, the tale illustrates tattoos taking over Parliament. As such, we are introduced to Canada’s rich and complicated history of commercial tattooing.

When I asked about tattooing in our Zoom call, Jelinski delves right in. He has loved tattoos since he started getting them in college. And he doesn’t stop at liking the drawings on his skin. He is interested in their history and the ecosystem that surrounds them, which, until Jelinski came along, wasn’t well documented in Canada.“I wanted to learn more about it in this distinctly Canadian context,” said Jelinski. “You could find a decent amount online, especially now about the United States, England, and a little bit of Europe. But the Canadian stuff… there was almost nothing to find on the internet. And so I was like, okay, I guess this is my job now.”

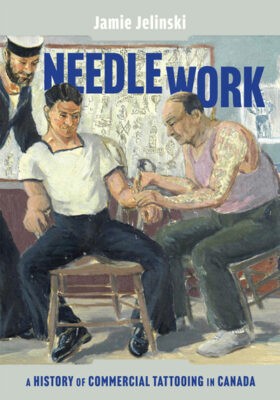

Needle Work McGill-Queen’s University Press

A History of Commercial Tattooing in Canada

Jamie Jelinski

$75.00

cloth

424pp

9780228021988

From his engagement in the Canadian scene emerges Needle Work, a captivating and comprehensive book. Jelinski, a Saskatchewan native living in Montreal since 2013, has been diligently working on this book for the past ten years, traversing the country to research and unearth the lost history of tattoos. Jelinski’s book isn’t about people who get tattoos, a subject that has been studied extensively. The art historian and future lecturer at the University of Liverpool unveils the unknown history of the tattooists that left an indelible mark on art in Canada.

“I focused on tattooing as my object of study,” Jelinski tells me in our interview. “Everything else is kind of secondary. Those histories of the cities, the histories of law enforcement and regulation, the history of art – all of these things I tried to bring together through the lens of tattooing.”

Needle Work is an easy read, as it is divided into chapters that focus on each Canadian city’s contribution to commercial tattooing rather than following a linear, chronological retelling of history. Events intertwine one within another to create a patchwork that illustrates how every province and city brings a different part of tattoo history to the table.

The arrival of Japanese tattooers on the West Coast around 1891 marked the beginning of tattoos being practiced more openly. Murakami, a Japanese tattooist living in Vancouver, was the first commercial artist ever reported in Canada. Murakami’s designs fused cultural references, incorporating not only traditional Japanese imagery, but also blending in Western influences.

As Jelinski put it in our interview, “When you look at Murakami’s designs, he had the ostrich, which he pulled from a Japanese woodblock print, but he was also offering prototypical Western style imagery to appeal to as wide an array of customers as he possibly could because that was the name of the game. There was no reason not to try to draw people in.”

While most tattooists featured are men, most mention the importance of their female clients. If people thought that historically women got into tattoos way later than men did, the stories featured debunk this idea. In this way, Jelinski’s narrative is inclusive, ensuring that all voices in the tattooing community are heard and valued.

Needle Work’s bibliography is as dense as the book itself. When asked how he found the previously untold stories that make up the book, Jelinski described the extensive travels and meticulous research that brought him to the United States, Europe, and the coasts of Canada. He found discrepancies in stories, and filled holes left by reporters. He even went as far as getting access to FBI files for a chapter on Sailor Joe, a tattooer who lived multiple lives under different aliases.

Yet, Jelinski reminds me, tattooing practice was not a totally back-alley activity: Canadian tattooists “were working on the main streets of the big cities, trying to appeal to as many people as possible, like being profiled in the newspaper, advertising in the classifieds, and purchasing larger advertisements in newspapers. This pretty public activity has grown over time, with some ebbs and flows, specifically in the 1930s. And then things started to take off post–World War II. By 1970, there were a lot of tattooers.”

While tattoos might not have been considered part of mainstream visual culture before, Jelinski attempts to remedy this with his book. As meticulous as it is accessible, Needle Work is a valuable resource for anyone interested in art, history, or the evolution of tattoo culture. By documenting this overlooked history, Jelinski ensures that the stories of Canada’s tattooists will not fade away. mRb

0 Comments