“One chord is fine. Two chords are pushing it. Three chords and you’re into jazz,” American rock guitarist, singer/songwriter, and photographer Lou Reed once said. Seasoned jazz guitarist Peter Leitch, also a composer and photographer, would likely consider that an improvement. “I had no interest in the popular music of the day,” he relates in his memoir. “When you have been listening to Bird or Trane, Miles or Monk, or Clifford Brown, music on this level, how can you take the Beatles seriously?” Interestingly, Lou Reed never cared for the Beatles either. In fact, these two offbeat artists have shared a few key points, including heroin, a mistrust of the mainstream, and a long-term love affair with New York.

Leitch’s memoir chronicles an impressive career, recalling a lifetime of stages and studios shared with jazz greats, mapping the scene from the 1960s onward. The book is divided into three parts, based on the places where Leitch has lived – Montreal, Toronto, and NYC. The third chapter is the longest, honouring the gritty city that greased the guitarist’s groove: “I had never seen a place where most of the rules were ‘on hold’. As long as you didn’t commit a violent crime, no one cared what you did.”

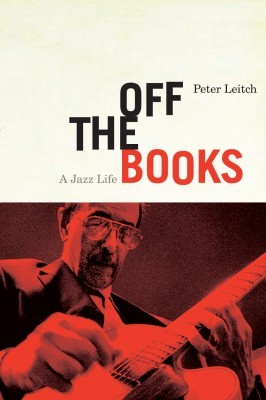

Off the Books

A Jazz Life

Peter Leitch

Véhicule Press

$20.00

paper

188pp

978-155065-348-9

If Leitch’s own story were a 45, the B-side to freethinking would be estrangement. His memoir recalls recurring bouts of depression and significant entanglement with drugs and alcohol. His innate sense of alienation was reinforced by external circumstances, such as growing up Anglo in predominantly French-speaking East-end Montreal, though he came to consider this an advantage: “I now realize that not having any strong national or cultural identity was useful to me, in being able to easily move in and out of different cultural and ethnic situations as an individual.”

And move he did, his infatuation with jazz heightened by each new lead. Luckily, his thirst for musical mastery eventually trumped his cravings for heroin, perhaps saving him from a premature coda: “I was too serious about music and my wife and I decided to kick,” he recalls, underlining the importance of having a “strong motivation in some other direction” when beating addiction.

Leitch’s writing style is casual and conversational. While this can be refreshing, one wishes occasionally that he would slow down a little, taking care to craft more memorable images. Quick summaries like “we had a brief relationship that didn’t work out for various reasons,” leave the reader wanting for details and depth.

That said, his confessions on the highs and lows of his “jazz life” are courageous. As many artists will attest, self-doubt has a way of creeping in through the back doors of ill-attended gigs, littering red carpets with unpaid bills. Leitch bravely admits he was not immune. Despite his great achievements, his sense of dignity dangled like a broken guitar string when resources and recognition were low.

In this sense, the book will resonate not only with jazz enthusiasts, but also with any artist who has been tested by fickle crowds or critics, and yet carries on. In 1973, Rolling Stone Magazine called Lou Reed’s Berlin album his “last shot at a once promising career.” In 2003, they included it on their list of 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. It only took thirty years for the world to catch on; meanwhile, Reed just kept pushing forward.

At sixty-eight, with multiple music and photography projects in the works, Peter Leitch is fortunately doing the same. “Artistically speaking, I’m not going to go quietly,” he declares. mRb

0 Comments