Look at the back cover of On Loving Women and, down in the bottom left corner, you’ll see a bar code. Its presence, of course, is nothing remarkable in and of itself. Every book needs one, and designers, as a rule, tend to incorporate them as inconspicuously as possible. In this case, though, it’s uncommonly prominent, not just larger than usual but contained within the shape of a cartoon heart. I know what you’re thinking, and yes, in almost any other conceivable context this is the kind of thing that would be revoltingly twee. But don’t be put off, please, because by the time you’ve finished Diane Obomsawin’s sweet, generous, poignant book, you’ll find yourself thinking that a heart- shaped bar code, with its dual implication of romance and more prosaic human interchange, is the perfect teaser for what’s inside.

On Loving Women is a graphic novel, but only in the loosest sense of that often-ambiguous designation. Montreal- born Obomsawin, who made her English-language debut in 2009 with a comics version of the life of nineteenth- century German foundling Kaspar Hauser, has gathered 10 sexual awakening/coming-out accounts – her own and those of nine other women – and told them in discrete chapters: “Mathilde’s Story,” “Maxime’s Story,” etc.

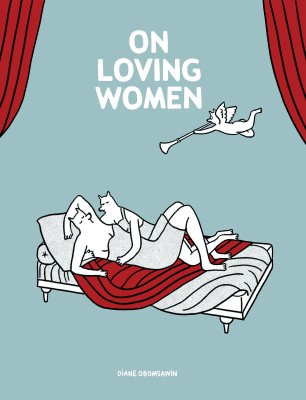

On Loving Women

Diane Obomsawin

Translated by Helge Dascher

Drawn & Quarterly

$16.95

paper

88pp

987-1-77046-140-6

For all the variety in the stories Obomsawin is presenting here, her subject has become fairly common. What really sets Obomsawin apart is a counterintuitive but ingenious choice she makes in depicting her characters. A fair clue to that can be found in “Mathilde’s Story”: “Recently, I’ve come to realize that all the women I’ve ever loved … have horse faces.” Notice it doesn’t say “horsey” or “horse-like” or “equine.” That’s because the women in question literally do have the faces of horses.

For all its realism, then, On Loving Women is also surreal. The characters’ bodies are comically elongated, more or less human, but the heads and facial features anthropomorphically incorporate elements from various mammals: horses, yes, but also dogs, pigs, rabbits, and unidentifiable hybrids thereof. What might appear at a glance to be a distancing device actually has the paradoxical effect of throwing these human stories into relief and bringing the reader closer to the characters; the slight skewing lets us consider, with a new clarity, narratives that we might otherwise be tempted to take for granted. Similar strategies, to different ends, can be found in works as far-ranging as Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Matt Groening’s Life In Hell, so if you’ve appreciated either of those, there’s no reason you can’t take the leap with Obomsawin. mRb

0 Comments