British explorers who ventured into the Arctic were a stubborn sort. Though many of them possessed the unrelenting tenacity and unstoppable work ethic memorialized in song, it was the nearly universal refusal to change their ways that truly defined European seekers of the Northwest Passage.

I refer, of course, to the decades-long refusal to learn from Inuit, the Indigenous inhabitants of the Arctic. In the thousand years and more before frontiersmen like John Franklin arrived with the best equipment available, Inuit had developed technologies – the snow house, the kayak, sleds pulled by dogs, caribou-fur parkas – and a world-view that allowed them to survive and even thrive in the extreme cold of Arctic winters.

The Europeans considered Inuit ways to be so inferior as to be unworthy of consideration. They refused to eat seal meat, insisted on using ungainly ships, and wore clothes made of fabrics that became useless and dangerous in wet conditions. The results, again and again, were disastrous. British explorers and their crews perished in harsh Arctic conditions, in many cases resorting to cannibalism – refusing until death the Inuit methods that would have saved their lives.

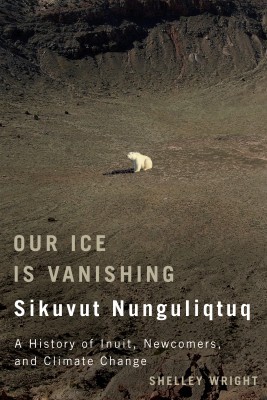

Our Ice is Vanishing / Sikuvut Nunguliqtuq McGill-Queen’s University Press

A History of Inuit, Newcomers, and Climate Change

Shelley Wright

$39.95

cloth

420pp

9780773544628

Wright’s book lucidly renders the arrogance of the qallunaat (the Inuit term for southerners) and its results: the trauma wrought by residential schools, the starvation and misery of forced relocations, the exorbitant cost of food and the total inadequacy of the imposed sedentary living conditions, the disregard for impacts of resource extraction on the animals and ecosystems that Inuit still depend on for their survival and way of life.

Colonial arrogance and its horrors are on display in Our Ice is Vanishing, but it’s the historical facts that are polemical, not this book. Wright’s work is an ambitious synthesis of climate change analysis, history, mythology, and storytelling – an attempt to build a bridge where walls have prevailed for centuries.

The book walks its culturally sensitive walk by presenting Inuit knowledge, mythology, and worldview alongside European history. The Inuit version of events, on the level of empirical accuracy, often compares quite favourably to the qallunaat version. For example, Inuit knew – and would tell anyone who asked – where the Franklin expedition’s boats sank. It took a hundred years, big budgets, and cutting-edge technology for Canadians to catch on. And even though Inuit accounts guided their high-tech efforts, southern Canadians are unabashed about cutting Inuit out of the picture. Prime Minister Stephen Harper, in a gleeful opinion piece for The Globe and Mail, celebrated the “discovery” of Franklin’s ship as bolstering Canada’s “Arctic sovereignty.” He does not mention Inuit once.

In Sikuvut Nunguliqtuq, historical accounts of Inuit groups travelling thousands of kilometres blend with surprising, moving stories (including tales of Kiviuq, a sort of Inuit Odysseus) to reveal the deep Inuit relationship with the land and the animals of the Arctic. The fact that it lets Inuit writers, storytellers, and leaders do much of the talking makes it a refreshing break from endless qallunaat pontificating about “the North.”

For Wright, Inuit are “witnesses and messengers of climate change,” and have much to teach us qallunaat about sensitively observing our environment. “There can be no learning,” an Inuk elder tells her, “and no good life without listening and keeping an open mind and heart.”

If we qallunaat could find a remedy for our colonial hangover, Wright seems to say, we’d have a lot to learn from Inuit: an ethical relationship with the ecosystems that sustain us, a fine-tuned awareness of climate change, and a head start on how to adapt to it.

Perhaps because Sikuvut Nunguliqtuq is mainly a work of history, Wright is a bit more gentle with the players of the present. “Incoming southerners bring their preconceptions with them,” Wright suggests, and they “may be recommending policies that have little to do with the realities on the ground.”

Wright breaks from this kind of massive understatement by noting in passing that the federal government is committing “gross negligence” of its obligations under the 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. Unmentioned is a billion-dollar lawsuit brought by the Nunavut Inuit against the federal government on account of this neglect. The dispute boils down to this: Canada got title to one-fifth of its land mass, and Inuit who live there got broken promises.

The deep, painful irony is that the federal government is spending hundreds of millions of dollars to send qallunaat workers to fill government positions as administrators, technicians, teachers, and police; they often know little of Inuit culture, and seldom bother to learn. Training Inuit to fill the same government positions would actually save money. Echoing their explorer forebears, Ottawa is willing to spend money to keep Inuit in a state of desperation.

Wright may have plenty of reasons for taking a gentle approach, but the impacts of the history told within her book can hardly be overstated: Canada’s hostility to Inuit, enabled by our prevailing colonial attitude, is the primary cause of the ongoing social and economic crisis in Nunavut. When qallunaat take responsibility for that relationship, we’ll begin to learn what Inuit can teach us. mRb

A terrific review of what sounds like a profoundly valuable book.