Julie Delporte and I don’t know each other well, but we’ve interacted a few times in and around zine and comic events in Montreal. Delporte’s skillful and sensitive use of coloured pencils, coupled with her prolificity, have always impressed me. By my count, Portrait of a Body is her thirteenth book, not including zines. I have read her work in both English and French over the years – often delightfully encountering her books in our public library system. Her drawings often transport me into a dreamlike trance where time is suspended, and I find myself wondering about the corners of under-examined dreams and memories.

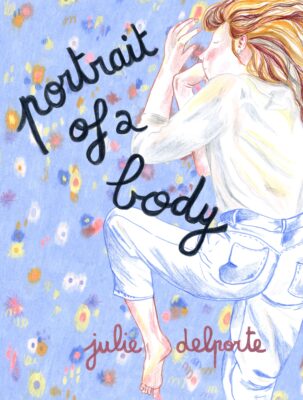

Portrait of a Body

Julie Delporte

Translated by Helge Dascher and Karen Houle

Drawn & Quarterly

$39.95

paper

268pp

9781770466807

While Delporte doesn’t shy away from depression and sorrow, Portrait of a Body is less steeped in sadness and solitude than her previous work. In this book, Delporte’s “Dear Diary” style of storytelling is more focused on trauma, healing, and layers of self- and social rejection. She explores questions of a hesitant, angry, and retreating sex drive, late-to-lesbian identities, and the layered discomforts of navigating perceptions of others on one’s own desires and what those perceptions could possibly mean and aid in uncovering.

It is in the drawings of this book where Delporte’s work shines and delivers the reader to new experiences of time and reflection. She uses coloured pencils in a way I can only describe as painting with them. I don’t mean she uses those watercolour pencils that you draw with and then paint over with water. What I mean is: Delporte’s ability to sensitively layer colour, and her range of light mark-making, evoke a softness in texture and feeling, on the page and within me, that is hard to reach. While the writing is straightforward, the drawings generously allow themselves to be explored and not fully understood.

The pages of Portrait of a Body are peopled with ambiguous shapes, and it’s this colourful and bold ambiguousness that I find holds the strength of this book. Are they opening-up landscapes? Rocks? Barnacles? Shells? Bedsheets? Are they large cross-sections of gemstones? Root systems? Brooks? Tears? Lichen? Flower petals? Leaves? In allowing the viewer to explore the nature of these images, we are able to linger on the edges of perception, and witness Delporte’s story of deepening and changing self-narration.

In terms of queer storytelling, I found myself hoping for more nuanced understandings of gender beyond biology. The book is at times unfortunately stuck in gender essentialism. In contrast to this, though, I was delighted by her briefly depicted moments of creative sexuality – in particular a story of sexual exploration using Moomin as a portal, and embracing Leonardo DiCaprio in Romeo + Juliet as a lesbian icon. There is another brief moment where Delporte describes making a room full of lesbians uncomfortable by singing a song about political lesbianism but not knowing why they were upset with her. I found these depictions of social discomfort compelling and just a bit under-explored. I wanted the writing in this book to leap or cautiously walk into the same ambiguous zones of the drawings, not needing to so quickly declare itself as one thing or another.mRb

0 Comments