When the cacophony of modern culture – the relentless buzz of infotainment – leaves me longing for escape, I read. My preference: a book, made of ink and paper with pages I can actually turn. Often, a bygone era beckons and history provides an effective form of time travel. Elaine Kalman Naves’ latest work, Portrait of a Scandal: The Abortion Trial of Robert Notman, throws the reader back to nineteenth-century Montreal. This history has it all: desire and illicit sex, privilege and penury, fame and infamy, the dramatic momentum of an absorbing novel.

On one of our many mon pays, c’est l’hiver days, when the sidewalk is a black-iced crevasse flanked by soiled, crusted snowbanks, I visit Kalman Naves at her home in NDG. Her manner is a rare and welcome mix of modesty and confidence. We settle in her sunroom burgeoning with well-tended plants and chat for several hours over hot tea and homemade blueberry muffins. In our rather clannish community, Kalman Naves is known for her generosity toward both peers and protegés: a few years back, she raced around town on a single autumn evening to attend no less than three book launches so that she could support all three writers.

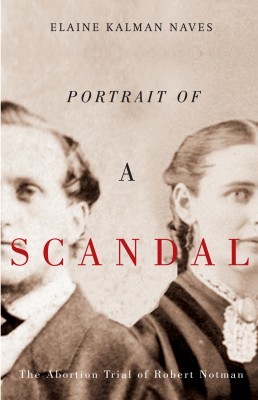

Portrait of a Scandal

The Abortion Trial of Robert Notman

Elaine Kalman Naves

Véhicule Press

$18.00

paper

214pp

978-1-55065-357-1

Though the events of Portrait of a Scandal took place nearly 150 years ago, the multidimensional characters and the themes of desire and downfall make this tale of our city both timeless and familiar. The book took Kalman Naves six years to write. “The research was challenging,” she tells me. “I had to find relevant pieces from archives, letters, and newspapers, which were nearly illegible; there were three separate accounts of what everyone said. Understanding the legal and medical complexities, not to mention finding all the clues to piece together the story, was demanding.” There were moments, she confesses, when she almost gave up. “My rule of thumb: If I can get to page 100,” she laughs, “I finish the book!”

In an incantatory rhythm reminiscent of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, the story opens with a portrait of Montreal during the late 1860s. “In summer it was a city of melons, strawberries, and sweet corn grown in backyards and bucolic outskirts…. It was a city of snow, ice, and tinkling sleigh bells…. It was a city of domes and spires…. It was a city of fur barons and clergymen, of nuns and belles….”

Kalman Naves has a novelist’s eye and a historian’s sleuth-like instincts, with the tenacity of both. Wisely, she presents the scandal through the lens of its time, rather than imposing contemporary views. Though this is a work of non-fiction, Kalman Naves deftly employs the tools of the fiction writer – intuition, empathy, and imagination – to create the thoughts and feelings of her characters where motivations and events are unknown or unclear. Many of these speculative sections, indicated by italics, compose the richest parts of the book. Here, Robert Notman is first beguiled by Miss Margaret Galbraith, a country girl hired to help with his father’s ablutions, who attended the McGill Normal School with dreams of becoming a teacher:

Again she recoils, so eager to flatten – even erase – herself that through the thin stuff of her blouse she can feel the nub of the rose-embossed wallpaper against her shoulder blades…. He craves to dissolve her reserve, unlock the secret cry that a woman shrieks when it goes well with her…. What the French… call la jouissance.

Kalman Naves took a risk by using her invented passages as mortar between historical facts. These interludes add layers to the characters and deepen the emotional resonance of the story.

Two-dozen photographs illustrate the text and help the reader step into the drama of the past, imagining what transpired beneath the surface of carefully arranged portraits. They highlight the dichotomy between the famous brother and the infamous one, “in whose wake tragedy inevitably followed.” What’s more, the black and white pictures underline a fascinating link between photography and scandal: both arrest time, both capture a moment and make it indelible.

The story abounds with irony and sly wit. William Notman flees Paisley, Scotland, for Montreal following his family’s bankruptcy and subsequent disgrace. While he becomes a renowned photographer, his brother Robert creates a scandal far worse than the one the family fled to escape. Sadly, the doctor who committed suicide unintentionally lays bare the sin he was trying to conceal. While society judged and vilified Robert Notman and Miss Galbraith, it wallowed in every juicy detail of the couple’s disgrace.

Though Kalman Naves’ books vary in subject matter, the common thread is history, whether personal, familial, literary, or Canadian. Born in Budapest, the child of two Holocaust survivors, she came to Montreal in 1959 at age eleven. Like many writers, she grew up a bookworm. “Both of my parents were great storytellers,” she says. “I thought it might be interesting to be a writer, but you had to suffer.” Kalman Naves studied North American History at McGill and her first job was at the Centre d’études du Québec. She began writing book reviews and had her own column in the Montreal Gazette. Nonetheless, her path to authorship was hard won with the proverbial papering of walls with rejection slips. In fact, Journey to Vaja, her family biography set against the backdrop of Hungarian history, was rejected sixty-seven times. “Journalism helped me hone my craft,” she tells me. A tighter, more trenchant version of Journey to Vaja was eventually published by McGill-Queen’s University Press (one of the original sixty-seven passes). The book was awarded the 1998 Elie Wiesel Prize for Holocaust Literature, was adapted for radio, and made into the documentary film Paradise Lost for the Canadian History Channel.

Its sequel and perhaps Kalman Naves’ best-known book, Shoshanna’s Story: A Mother, A Daughter, and the Shadows of History, is a wrenching memoir about her complex childhood in Hungary, England, and Montreal, set against the horrifying backdrop of the aftermath of the Second World War and the looming threat of the Communist Revolution. By dramatizing scenes and eschewing easy interpretation or analysis, this book reverberates long after its covers are closed. Shoshanna’s Story won the 2003 Quebec Writers’ Federation’s Mavis Gallant Prize for Non-Fiction, as well as the 2005 Canadian Jewish Book Awards Yad Vashem Prize for Holocaust Literature.

Kalman Naves says that she wasn’t intending to write about the Holocaust, but rather longed to “find the grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and half-sister whose faces surrounded me in photographs as I was growing up and about whom my parents spun tales from my youngest years.”

For Kalman Naves, writing is a practice. “What fulfills me most is the process,” she says. When I ask about her future goals, she pauses awhile before answering. “It’s kind of a prayer,” she says. “Please let me keep doing this.” mRb

0 Comments