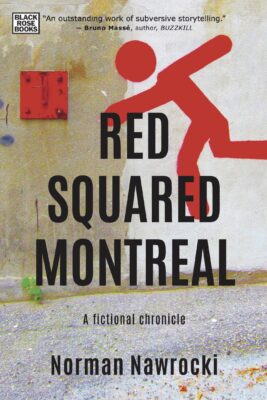

Norman Nawrocki’s Red Squared Montreal, “a fictional chronicle” of the seven-month 2012 Quebec student strike, is a love letter to a particular political moment. The novel celebrates the energy of street protest above all, and in doing so occasionally nails the Printemps Érable’s charm. The descriptions of the joy among leaderless strangers marching together are worthy salutes to experiences few others have chronicled. Montreal has never seen anything quite like the 2012 student strike, and Nawrocki captures images of the months of protest that will bring back intense memories for those who participated. Unfortunately, the novel struggles to capture the strike’s civic and emotional complexity, offering instead hyperbole and bathos and little sense of what it genuinely accomplished.

Red Squared Montreal

Norman Nawrocki

Black Rose Books

$19.99

paper

200pp

9781551648019

Unlike most students in 2012, Huberto and Pascale don’t own cell phones and don’t use or discuss social media (with which information about demonstrations was communicated on the fly). Like people of Nawrocki’s generation, they judge the merits of political actions based on how much coverage they receive in physical newspapers.

Huberto and Pascale believe the most hackneyed of protests (like drawing horns and moustaches on electoral posters) are revolutionary, and fondly chant shopworn slogans anarchists have shouted for decades. This lands awkwardly in a story set in 2012, neglecting the collection of hilarious chants improvised and taken up by students during the night marches. (For many, the sound of those protests was the sarcastic, dejected cheer, “Charest, woo-hoo.”) As such, the novel ignores one of the strike’s most engaging aspects, one that delighted participants and kept their morale up even as it communicated the collective humour of the movement.

The purity of the cause and the sense that this is a historic fight for good keeps Nawrocki’s characters going. They absurdly compare the tuition increase that strikers oppose to rape. Various international representatives are dropped into the text to affirm that SPVM crackdowns on students (which were vicious, but killed no one) are as bad as police in Guatemala, Peru, or Chile under Pinochet. A “Cossack” exclaims, “It’s even worse than in Russia!” Nobody suggests these comparisons are self-servingly false.

Bafflingly, Nawrocki presents incorrect facts. The novel identifies the first day of anti-protest Law 78 as May 22, when it was May 18, which few who protested that ugly, violent weekend could forget. The SPVM’s pepper-spraying of Bar le Saint-Bock took place the next night, but the novel sets it in April. At one perplexing moment, a march turns from Berri onto Pine.

Presuming facts don’t matter as much in a fictional chronicle, the most striking aspect of Red Squared Montreal is its incuriosity. Even as Huberto laments how the media “don’t speak to us,” none of the characters shows any interest in those who don’t participate in the strike, or oppose it. Pascale sums this attitude up by exclaiming “Baa! Sheep!” at the idea that a majority of students are voting to end their strike after seven months. Huberto and Pascale’s enemies are dismissed as selfish, ignorant, privileged, or brainwashed, but no one in the novel talks to anyone who doesn’t agree with them. Nobody in this book attempts to change anybody else’s mind. Those who remember 2012 as a year of exhausting, constant debate about the strike – at work, with family, among friends, on social media – will not see those experiences reflected here.

Does no one Huberto loves or respects oppose the strike? Mightn’t Jean ask Huberto how strikers will help unhoused poor people like him? How different would this novel have been set in a world where decent people disagree?

The strikers’ motivations are not closely explored either. While much of its dialogue and narration reads suspiciously like sloganeering about the justice of the cause, the book doesn’t consider what emotions and personal experiences might drive young people to engage for months in a sometimes-violent fight to improve the education system. This lack of concern for the personal struggles beneath the conflict flattens the dramatic scope so completely it leaves Red Squared Montreal with the moral range of an action movie.

The 2012 student strike deserves its own literature, and Red Squared Montreal succeeds at least in capturing the dizzy heights of the protests. As both anarchist and poet, Nawrocki often knows just the right words to capture the elation, camaraderie, and terror of marching in the street and facing off against contemptuous police. However, the lack of curiosity about the people behind the conflict means the novel ultimately fails to communicate the stakes and experiences of the 2012 strike in human terms.mRb

0 Comments