I was looking for a book that didn’t involve so much travel because my wife and I had had our first baby,” says Taras Grescoe, describing the origins of his latest, Shanghai Grand: Forbidden Love and International Intrigue on the Eve of the Second World War, over a messy plate of Mexican tortas.

In the course of writing six books and countless articles and travelogues, Grescoe has criss-crossed the globe, tracing urban public transit systems in Straphanger, following the supply lines of seafood in Bottomfeeder, and hunting taboo culinary delicacies in The Devil’s Picnic.

Shanghai Grand still takes Grescoe and his readers far from Montreal – not only to a distant land but also to a very different time. Its story unrolls in the streets, nightclubs, luxury hotels, and shikumen lane courtyards of Jazz Age Shanghai. Set mostly in the international settlement, the book presents this exceptional semi-colonial trading port on the eve of the Japanese invasion during World War II, with Mao’s communists gathering forces and Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalists strengthening their grip on the country.

This setting serves as a backdrop for a rich cast of real-life characters: a hyper-social iconoclastic proto-feminist writer, an aristocratic opium-smoking decadent Chinese poet, a double agent arms dealer-turned-Buddhist monk, and a fabulously wealthy Baghdadi Jewish baronet, to name just a few. They offer prime cinematic fodder, with a love story worthy of the big screen and enough side plots to be spun out into a serial – one reviewer went so far as to cast the principals. Digging deep into archives and period accounts, Grescoe transports his reader into the city’s sensory atmosphere and unique social climate.

“It allows you,” he explains, “to travel in your imagination and in time.”

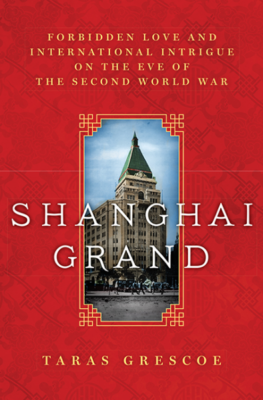

Shanghai Grand

Forbidden Love and International Intrigue on the Eve of the Second World War

Taras Grescoe

HarperCollins

$32.99

cloth

480pp

9781443425537

“One of them,” he says, “was a hotel that’s now called the Peace Hotel. One night I went in there to this old bar, and there were a bunch of Chinese jazz musicians playing old standards like ‘Begin the Beguine’ and ‘Slow Boat to China.’ I ordered a badly mixed drink and got a little drunk and hung around all night pretending to be a romantic old China hand. But I fell in love with the hotel, which had obviously been beautiful in its time.”

Once known as the Cathay, this splendid building on the Bund was constructed in the 1920s by textiles magnate Sir Victor Sassoon. In its prime, it was the elegant cornerstone of his considerable domain and among the most glamorous addresses in the Far East, a symbol of the era it still evoked on Grescoe’s visit three-quarters of a century later. It stirred his resolution to write something about the city’s quixotic heyday and to seek a subject who offered him access to that world. Grescoe finally found Emily “Mickey” Hahn, a peripatetic American bon vivant who regularly published in the New Yorker and wrote some fifty-four books over the course of her lifetime.

Hahn travelled widely, independently, and very unconventionally. Before going to Shanghai in 1935, a two-year stint in the Belgian Congo saw her learn Swahili, temporarily “adopt” a Pygmy child, and navigate a lengthy jungle trek alone on foot. Her well-documented time in China afforded Grescoe connections to a cluster of themes: her opium addiction hinted at the scourge of the Middle Kingdom that cracked China open to European trade; she lived lavishly as an expatriate among impoverished locals; and she was well-connected in Chiang Kai-shek’s inner circle, as well as in the expat community of the international settlement.

While Shanghai Grand is primarily about the history and political trajectories that shaped the city, it’s the tale of Hahn’s interracial love affair with poet Zau Sinmay that conjures the spirit of the place. This tactic structures the book, which offers a portrait of geopolitical turmoil, then triangulates between its cosmopolitan characters to show how their lives were shaped by this upheaval. Sassoon builds and later forfeits the Chinese corner of his empire, while Hahn begins then abandons her liaison with Zau, takes up with a British intelligence agent, and barely escapes intact as the war finally reaches the international enclave.

“If I couldn’t do the travelling myself, couldn’t travel back in time to this lost Shanghai, I needed someone who was really present and really taking notes about the place,” says Grescoe. Hahn’s copious journals gave him insight into her thoughts, impressions, and sensations, and she also wrote several times weekly to various members of her large family. Additionally, nearly twenty local daily newspapers chronicled the minutiae of the city, from incoming ships to movie listings. Victor Sassoon also kept a detailed daily record, complete with snapshots of the people he met.

“I didn’t really know how to do historical literary non-fiction with scenes that read like a novel, so I wanted to figure out how much I could let myself get away with in reconstructing the characters’ thoughts and minds,” Grescoe explains. “I was lucky, because these people recorded their lives quite frequently, so I didn’t really have to colour outside the lines very much at all. Mostly I was reconstructing scenes that they had recorded – like, there’s a scene with Victor Sassoon in the hotel in 1932 when a bomb goes off, and he recorded that very well in his journal. And Mickey Hahn was such an inveterate self-chronicler that often one incident in her life would be recorded in several ways, in published things in the New Yorker or in other magazines, in her books, in fiction, in non-fiction, and in letters, too, so you kind of get at the truth.”

Shanghai Grand is the story of a passionate romance that’s also an augur of China’s political landscape at an extraordinary and decisive moment in the country’s recent history. This era, Grescoe argues, is a key period for anyone who wants to understand China’s geopolitical status now.

“If you don’t understand Shanghai’s history, you’re not going to understand China today. And if you don’t understand China today, then you’re not going to understand what’s going to happen in the world tomorrow.”

The real star of Shanghai Grand is the internecine metropolis itself, a place that burned brightly before being extinguished by a swift succession of revolutions and wars, eventually being rebuilt as something wholly different. Grescoe is clearly smitten with a Shanghai that’s already lost but only now disappearing. When the city fell to Japan, so did an era, and this book is also a eulogy for that lost moment, captured in what he calls the “vanishing architecture” of the period.

“The time had passed,” he writes toward the end of the book, “when a person could step off a ship and talk his or her way into a garden party or a brand new career, bluffing the world with a convincing manner and a compelling cover story. Shanghai continued to exist, but in name only. Never again would it be the world’s most fabulous haven for fabulists. What the world gained in probity, it lost in romance.” mRb

0 Comments