Early on in Shola von Reinhold’s 2020 debut LOTE, a distinction is made between an Arcadian personality type and a Utopian one. Arcadian personality types look to the past for inspiration whereas Utopians seek out their ideals in the future. LOTE’s narrator, Mathilda, a biracial academic and archivist of sorts, immediately identifies as Arcadian – a sensical conclusion for any researcher at heart. The text takes this further with the consideration of Mathilda’s Blackness, the criticality of which ultimately widens von Reinhold’s novel to the genre of historical fiction.

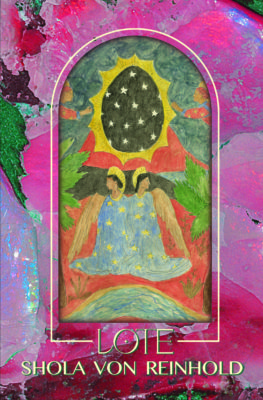

LOTE Metonymy Press

Shola von Reinhold

$21.95

paper

456pp

9781777485245

Mathilda recounts a series of “Escapes” motivated by historical “transfixions.” For Mathilda, these processes serve as essential survival tools. She is able to move through the world, as a Black queer woman, by latching onto historically inspiring figures (the first of whom are white), making Mathilda’s ultimate discovery of Hermia Druitt, a Black Modernist poet, all the more rupturing to her personhood. Druitt becomes a point of obsession for Mathilda, driving her to apply for a Dun Residency (founded on the aforementioned theories of Garreaux), as well as the point of resource for Druitt’s mid-nineteenth-century secret: the titular Order of the Lotus-Eaters or “Lote-Os” – an organization dedicated to luxuries, and arguably, to taking up space.

LOTE is a text filled with yearning and brief pockets of fulfillment. Mathilda is either confronted with the cruel dismissals of her fellow Garreaux-obsessed peers, Griselda and Hector, or exhilarated by each uncovering that brings her closer to Druitt. She meets a pivotal figure in Erskine-Lily, a queer, non-binary person who, like Mathilda, found salvation in Druitt’s unabashed personal pride. Of Erskine-Lily, von Reinhold offers Mathilda something otherwise unknown to her – a living, breathing “transfixion.”

Von Reinhold’s command of language mimics that of an academic, using gothic-like prose when musing on the year 2007. I wouldn’t say it’s the most readable text, but in line with its own overall question, why should it be? Von Reinhold’s intention to subvert norms is made clear from the very first pages. Mathilda amusingly remarks that she can’t quite remember the name of a co-worker, and that far too much time has passed to confirm it, and so the character is referred to throughout the entire book as “Elizabeth/Joan.” Even in the text, von Reinhold challenges the reader to not only reimagine the past, but to also restructure the present.

Though von Reinhold fictionalizes history, the book begs the question: who has yet to be unearthed? What is the real meaning of a canon, if there are so many hidden ones? Readers will find real joy in von Reinhold’s creation of what reads as a joyous Black artistic queer community. In placing luxury as the key totem of LOTE’s mandate, von Reinhold celebrates embellishment, extravagance, and not only “feeling seen” but being placed centre stage – demanding to be perceived despite a social insistence to remain hidden. Throughout the text Mathilda becomes herself until she finds, like Druitt, and like von Reinhold, “a threat to the established framework.”mRb

0 Comments