It is a fascinating paradox that the place of children has been largely ignored in discussions of war and conflict, even though a war may be the the defining event in a child’s life, shaping the entirety of their future. Curious as well, given how frequently the symbolism of youth is invoked by both sides in a given conflict: wars, we are so often told, are fought to protect our children, even if it means killing the children of others.

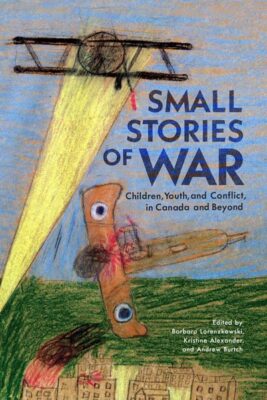

Small Stories of War, a compilation of current academic research edited by Barbara Lorenzkowski, Kristine Alexander, and Andrew Burch, ranges from the present day – including conflicts in Uganda, the former Yugoslavia, and Afghanistan, among others – all the way back to the First World War. The collection examines how young people have encountered and responded to armed conflict, as well as how they and their families make sense of and navigate war and its aftermath.

Choosing youth as a vehicle by which to examine conflict obviously provides a unique perspective. Young people are political actors stripped of all political agency – unavoidably a part of conflicts that may even be fought, euphemistically, to protect them, yet largely ignored throughout history by the historical study of war. This volume fills a considerable void, demonstrating that youth are witnesses to the effects of conflict, both in war zones and on the home front.

Small Stories of War McGill-Queen's University Press

Children, Youth, and Conflict in Canada and Beyond

Barbara Lorenzkowski, Kristine Alexander, and Andrew Burch, editors

$39.95

paper

392pp

9780228016854

The contributors include a number of accomplished academics, nearly all of whom are Canadian, teach at Canadian universities, or work in the realm of Canadian public history. The research in Small Stories of War could form a foundational “Canadian School” of child and youth studies as they relate to conflict. The extensive and comprehensive bibliography, as well as copious endnotes, form a valuable and self-contained academic resource and useful guide for further research.

And though it is evidently geared towards an academic audience , Small Stories of War nonetheless makes for compelling reading, and provides insights that would be valuable to a broad audience, including scholars, social and aid workers, health professionals, and educators (among others). This volume will doubtless provide practical insight for people who may find themselves working with children affected by those wars. Unfortunately, it does not address the grim fact that so many adults tacitly, overtly, and consistently support so many wars that destroy so many young lives. This is not to criticize the contributors – this concern is beyond the purview of the book.

The chapters of the book’s fourth and final section place a focus on “epistemology and evidence,” addressing “the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known.” As the editors note, court proceedings, welfare reports, case histories, and so on are prepared and collected by authorities with an aim to organize knowledge as much as “regulate and discipline subaltern groups such as children and youth.” As such, the primary sources they produce – sources that have historically been given primacy over practically all others – differ considerably from those produced by children and youth themselves. In keeping with the book’s spirit of examining the “small stories of war,” I felt it best to “start at the end” with “In the Spotlight,” which contains brief analytical essays on the production and presentation of young people’s voices, such as through drawings, oral histories, and children’s letters.

One chapter from this final section examines the correspondence between Canadian children and their fathers at the front during the First World War.Though the children’s letters were often highly formulaic, this in turn reflected the norms and conventions of the era, and by extension, the sense of normality at home. The correspondence contrasted sharply with the violence and fear experienced by the soldiers on the battlefield, providing them comfort in knowing that life proceeded normally at home, while offering further incentive to make it back. The children’s letters – as much as the act of letter-writing – played a considerable role in the patriotism and propaganda of the war effort.

This contrasts with the material culture generated by Bosnian children in the late 1990s, which took the form of a series of paintings and drawings collected by a Canadian Forces engineer working on demining operations, and was ultimately turned over to the Canadian War Museum for preservation and interpretation. Here, children depict the consequences of a mine strike – images of a maimed child who ignored warnings against playing soccer in a field are common. Though these drawings likely reflect imagery used in mine safety education, they may also reflect lived experience of mine-related violence. Whereas the letters written by children on the First World War home front meant to convey calm and normality to their fathers, the Bosnian children’s drawings confirm their understanding of a new, violent reality imposed by conflict and its aftermath.

The chapter concerning Cold War civil defense planning in Canada is a fascinating examination of the social, cultural, and political impacts of planning for the war that risked ending human life as we know it. Rather than bolstering patriotism and inculcating the public with a sense of resolve, ineffective and inadequate civil defense planning undermined parents’ faith in government and made cynics out of Canadian teens. Though the government sought a kind of “domestic containment” of emotions, one that would keep Canadians calm so they could carry on after a nuclear strike, the real and obvious limitations of those plans exacerbated the very fears civil defense training was meant to suppress. Growing up with such an existential crisis likely nurtured the anti-war and disarmament movements that characterized Canadian society at the end of the Cold War.

It is impossible to read this book without considering the impacts of current wars, be they in Ukraine or Gaza, on the children unfairly caught in the crossfire. As horrific images of dead and dying children, deliberately targeted, appear with greater frequency yet are insufficient to compel politicians and policy makers to change course, one wonders what sickness pervades our society, such that the deaths of innocents — irrespective of the condition of their births — could ever be considered acceptable in a supposedly moral and just society.mRb

0 Comments