In this ambitious book, Marcelino Truong tells his family’s story, intertwined with a history of the onset of the Vietnam War and contemporary reflections about that time. Truong offers a rare perspective for Western readers – that of a Vietnamese French person who experienced the conflict first hand. Originally written in French, the book has been translated to English by David Homel.

Truong had an eventful childhood. Son of a Vietnamese diplomat and a French woman, he spent his early childhood in Washington, DC, where the Truongs enjoyed a peaceful life in “a quiet middle-class suburb, something Norman Rockwell might imagine.” Truong describes this period as nothing short of idyllic: jazz on the car stereo, picnics by the water, white Christmases. But things take a turn for the worse when his father is summoned to Saigon by the South Vietnamese government and the family has to leave America, under the protests of his mother.

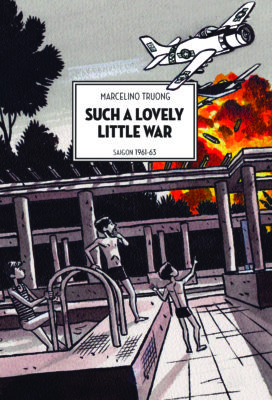

They arrive in Saigon in 1961, amid a divided Vietnam. Truong describes a tense city, with a strong military presence, but no signs of the direct conflict that was taking place in the countryside. It’s still the “Lovely Little War” of the perversely ironic title, a conflict to which the world was not paying very much attention, even as it was taking the lives of a thousand Vietnamese people a month.

Such a Lovely Little War

Saigon 1961–63

Marcelino Truong

Translated by David Homel

Arsenal Pulp Press

$26.95

paper

280pp

9781551526478

Truong approaches the war itself as a historian, narrating the conflict after years of careful research. We are also privy to the unique perspective of his father who had extraordinary access to the inner workings of power thanks to his role as President Ngô Dinh Diêm’s interpreter. Truong uses a colour device to switch between the personal story and the big picture of history: testimonies, dialogues, maps, newspaper clippings, etc., are shown in a colder wash of black and blue. This blue-red oscillation is only broken by the full-colour panels that are found at the opening of each chapter and in the conclusion, which depicts a contemporary conversation with his elderly father.

In Saigon, the children live a sheltered existence, punctuated by the war. When the Americans escalate the conflict by sending more weapons and troops, the Truong boys become increasingly more enthralled by the grandiose machines of destruction. They show a resilience that can only be attributable to the innocence of the very young. The occasional bombings in Saigon affect the children less than their mother’s nervous condition. Yvette has undiagnosed bipolar disorder and Truong’s characterization of her tends to hit on the single note of her temper tantrums. If not for the inclusion of her eloquent letters to her parents at the time, her character would fall completely flat.

His father’s portrayal is much more nuanced. A deeply reflective and kind man, he strove to understand the regime with which he collaborated, a regime that committed so many atrocities. It was this search for understanding that moved Truong to create this ambitious project, and the result presents the reader (and perhaps the author) with more questions than answers. A second volume, not yet translated to English, may offer some closer. mRb

0 Comments