“Trauma,” in Greek, translates to the English word “wound,” and Nour Abi-Nakhoul’s debut novel, Supplication, begins with an infliction. We meet the novel’s unnamed protagonist in the belly of a damp, bug-infested basement, where she is held captive by a grotesquely sweating and salivating (but otherwise ambiguous) man, her torturer.

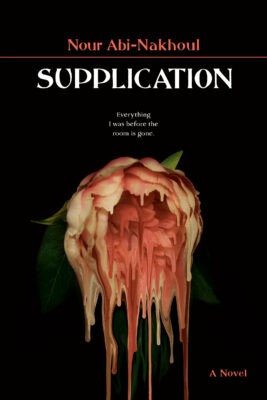

Supplication

Nour Abi-Nakhoul

Strange Light

$24.95

paper

216pp

9780771006074

Abi-Nakhoul, who moved to Montreal in 2019, and is now the editor-in-chief of Maisonneuve magazine, began writing the novel with what she calls an “almost a theological framework of pain and suffering in mind.” She explains: “I was thinking of this idea of pain or suffering, of trauma, as a kind of creature, a thing with agency.” In Supplication, the protagonist’s pain takes the form of a child that lives inside of our narrator’s body – she is pregnant with pain, the lasting effect of her wound. The novel’s surreal aesthetic allows for this unborn baby (or inner child) to be both figurative and very real at the same time – the narrator is not literally pregnant, yet her every move is dictated by this entity that she carries. The violent actions that the narrator does to other people and to herself are all at the urging of the twisted pain-child.

In this way, pain becomes almost contagious, spreading itself, proliferating. This is true, says Abi-Nakhoul, for real life, too: “That is the key to violence and pain. It does want to spread itself throughout the world, does want to multiply itself, and the imagery in the book gets to that in a visceral way.” One only has to think about the snowball effects of war (today in Palestine, Ukraine, Eritrea) to know this rings true. On a more personal level, those who have been in intense pain (emotional or physical) will also know this ebb and flow intimately. Violence begets violence; an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.

Fittingly, Supplication is not a book that one reads for plot – in fact it’s quite difficult to remember exactly what happened, or in which order. The strength of the book lies in its emulation of pain as a mood or feeling – of being inside a suffering mind. A certain rhythmic nature emerges in the novel’s imagery and pacing – a moment will fill with an abundance of descriptive energy, of thoughts that repeat and loop and are so full of imagery that they might burst or break, and then they do; there is a release (often in the form of death, burning, vomit, or blood) and an emptier moment follows, a brief respite, before the writing starts to fill up once again. The pattern repeats.

The hijacking power of pain is captured in the book’s very title. Supplication, or the act of supplicating, is defined in Merriam-Webster as “to make a humble entreaty” and is usually used in reference to relationships with a higher power, like God or the law. “The title of the book,” explains Abi-Nakhoul, “is about a pleading to have something greater take control. Which I feel is a very human drive, especially after something traumatic happens. When something really intense destroys your understanding of the world, there is a desire to bow down before something greater and have it take control of you, lead you, and construct the meaning of reality.” The pain-child represents, for Abi-Nakhoul and for the narrator, a “kind of purpose that you want to completely supplicate yourself before, something to guide you through the world without you having to think.” This, she continues, “is not something positive. We see that in a lot of people that have gone through trauma. People who throw themselves down before religion or law or whatever, any type of cultish institution.”

This accounts for what feels like the dream-like, or video game-esque, logic in which Supplication unfolds. Characters appear out of the blue to hand the narrator a weapon or take her to a place she needs to be. Doors open for her; lights appear conveniently in the distance. The pain-child within her tells her where to go and what to do. It’s as if a path has already been set out; all she must do is follow it.

It also explains the bug imagery that plagues the novel: “Insects,” says Abi-Nakhoul, “are things that have no real individual identity or autonomy, and are thrown down before this grand drive that they have no power over and that guides their movements. So, it’s almost an ideal for the narrator, but also something that she feels disgusted by. She wants to be an insect laying down before a grand drive, but she simultaneously rejects that. She is very lost.”

The final few pages of Supplication bring this fated rhythm to a cryptic end. Our hero’s thoughts are haunted by memories of the damp basement where we began, muddying reality for both the narrator and the reader. Abi-Nakhoul left this purposefully open-ended: “It’s finally up to her to make that decision,” she explains, and by extension, it becomes the reader’s decision to make too. But Abi-Nakhoul reveals a second reason for the enigmatic nature of her ending: “A part of it was that I didn’t want to end on a really depressing note. I didn’t want the narrative flow to be miserable like that, I wanted to leave space for hope. I started to feel kind of bad for her as a character, because it was pretty horrible, what I was doing to her, writing her into this kind of book.”

Abi-Nakhoul’s growing empathy for her character shows us that pain and violence are not the only emotions that can spread; kindness and hope can be contagious too.mRb

0 Comments