Stories of English-Montreal bourgeoisie, benefactors, and impressive commissions abound in this exhaustive look at one of our most prolific architects: Andrew Thomas Taylor. As the book’s author, Susan Wagg, points out, very little to date has been written about Taylor, and The Architecture of Andrew Thomas Taylor: Montreal’s Square Mile and Beyond aims “to fill this gap and to add to the woefully few monographs devoted to Canadian architects.”

We quickly learn of the architect’s vast imprints on many key projects in the city: in 1891 he was commissioned to design McGill’s Redpath Library, and “by the time he left Canada in 1904, the majority of McGill’s purpose-built buildings were his.” Furthermore, one of his major projects was to renovate the Bank of Montreal’s Head Office, still standing in Place d’Armes. Taylor helped found the Province of Quebec Association of Architects (PQAA) in 1890 and McGill’s Department of Architecture in 1896. He served on various committees, organized exhibits, and even taught. He was knighted in 1926 and received the Medal of the City of Paris in 1919. In short, his name should also be stamped on most of the notorious pierres grises of the majestic Golden Square Mile.

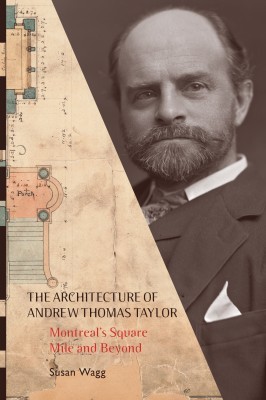

The Architecture of Andrew Thomas Taylor

Montreal’s Square Mile and Beyond

Susan Wagg

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$39.95

cloth

227pp

978-0-7735-4118-4

The book is chronological, beginning with his birth in Edinburgh in 1850, and ending with his death in England in 1937. Architecture buffs will revel in building details and descriptions. Others might find themselves reaching for Wikipedia when reading sentences such as this one: “To the left [of a three-story façade] was a ‘Tuscan Gothic’ motif: a pair of barely pointed windows separated by a mullion with a single circular light in the spandrel beneath an arch to match the entrance. Pointed windows filled in the next level between the buttresses. On the upper level a triplet of similarly arched lights were set under a relieving arch in the gable. The peak contained three tiny lancets.”

Architectural styles are often thrown around – “the Shingle Style,” “the Kentish vernacular,’’ or “the High Victorian’’ – meaning some background in architecture is handy; however, the book, for the most part, reads effortlessly even for those less fluent in the vernacular of arches.

Anecdotes, such as the one about Taylor’s discovery of elevators in New York, make this book an enjoyable read: “‘No one,’ he said, ‘thinks of laboriously climbing up numerous flights of stairs. There is an attendant all day long in charge of the elevators. You step in, and almost immediately step out at the floor you wish.’” We see a side of Taylor we would not have if we were simply looking at his sketches.

Anybody not yet acquainted with Andrew Thomas Taylor should pick up this book. Wagg has certainly drawn a rich portrait of Taylor, helping to ensure that “a sufficient number [of buildings] survive as visual reminders of this nation’s past.” mRb

0 Comments