Guido Nincheri is recognized as the most prolific Montreal artist of stained-glass windows and frescoes, but it was not his intention to settle in Montreal when he arrived with his bride in 1913. The newlyweds were originally headed to South America when the possibility of war in Europe changed their plans. The artist is most often cited for his fresco depicting Mussolini in the apse of the Madonna della Difesa Church in Little Italy, a work that caused the Nincheri family much grief during World War II. In The Art and Passion of Guido Nincheri, biographer Mélanie Grondin describes the artist in various phases of his personal and professional life. She examines Nincheri’s artwork, in Canada and the United States, in great detail and includes thirty-two colour plates of his art.

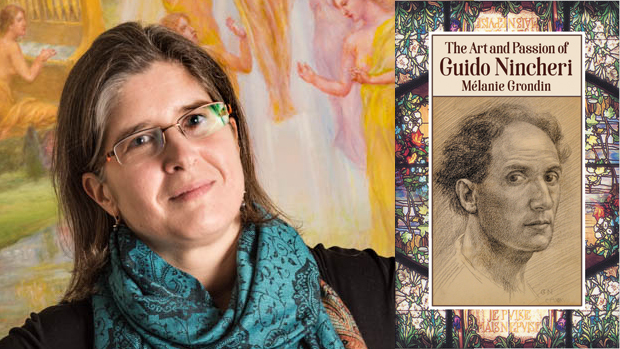

Grondin, a translator and the editor of the Montreal Review of Books, has also published short fiction and poetry. She has spent the last seven years immersed in Guido Nincheri’s world, becoming well versed in his artistic production. I recently spoke with Mélanie Grondin about her passion for the artist and the making of her book.

Licia Canton: The Art and Passion of Guido Nincheri is written with enthusiasm and tenderness. It was a very pleasant read. I really appreciate the amount of detail in the descriptions of Nincheri’s artwork. It’s evident that this was an enormous project and that you’ve done a lot of research. You took Italian-language, Renaissance art, and stained-glass window classes to better understand Guido Nincheri’s world. You visited numerous churches and buildings to see Nincheri’s art, and you’ve walked the streets of Florence to better imagine his years as a student. How did you decide to take on such a huge project?

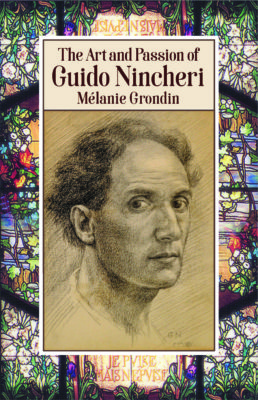

The Art And Passion Of Guido Nincheri

Mélanie Grondin

Véhicule Press

$24.95

paper

240pp

9781550654851

LC: What gave you the most satisfaction while working on this book?

MG: Whenever I discovered something that nobody else knew about. For instance, nobody really knew when Nincheri arrived in Montreal. Many were saying it was in 1914, but I discovered that it was in November 1913. On the Ancestry website, I found a “Declaration of Passenger to Canada” form he filled out when returning to Canada in 1923. In it, he wrote that his previous entry into Canada had been “Nov. 1913.” I also found the passenger manifest of the SS Canopic, the ship he took from Italy to Boston. But I was most excited about the discovery of eight letters he sent his mentor in Italy. They contained information about his stay in Boston and his first years in Montreal. Information that was, until now, unknown.

LC: How much time did you spend researching the book versus writing it?

MG: I started working on the book in earnest in 2011 and I started writing in 2013 when Nancy Marelli, my editor, said I needed to stop researching and start putting things on paper. Of course, I never really stopped researching, but if it hadn’t been for her I might still be only reading about Nincheri. Even during copyediting I had to research and double-check a few things. There is still so much research I could do, so many things I could add. I had to make choices.

LC: What was the greatest challenge working on this project?

MG: The biggest challenge was probably deciphering handwritten letters. It’s hard enough to understand old, European handwriting when it’s in your own language, but trying to read it in Italian was very difficult for me. I had to hire a native-speaking Italian to transcribe the important letters so I could read the typed words and make sure I understood them correctly.

LC: You spent time in Nincheri’s art studio on Pie IX Boulevard. How did it feel the first time you were alone in the studio where Nincheri created his masterpieces?

MG: The first time I saw it, in 2004, the studio took me by surprise. It was a very odd-looking building on the outside – it didn’t fit with the surrounding buildings – and when I first walked in, the vestibule and hallway were dark and plain. I didn’t expect to find much aside from archives because the studio had been closed since 1996 and the building uninhabited since 1998. But when I entered the first room on the right and found a completed stained-glass window at my level, I was taken aback by its beauty and proximity. Then I visited the rest of the studio and saw that it was still just that – a studio. Where I had expected an empty building, I saw Nincheri’s office with his name on the door and some of the reference books he used on the bookshelf behind his desk. I didn’t expect to see a kiln or a workshop with tools and glass samples lying about. I was fascinated by everything, but I hadn’t started working on the book yet, so much of what I saw didn’t make much sense to me. I guess my first visit to the studio convinced me that, more than ever, Nincheri needed to be reintroduced to Montrealers. We had a complete, historic stained-glass studio in the city of Montreal – not in Europe – and nobody knew about it.

LC: Guido Nincheri was a very passionate man. He lived for his art. Your own passion for Nincheri and his art comes through in your prose. You write that “the overall effect of Nincheri’s work is peace.” How has working on this book affected or changed you? Besides the pride and satisfaction that goes hand in hand with having completed a long-term project, what is the book’s lasting influence on Mélanie Grondin?

MG: For one thing, I’ll never look at a church the same way. Now, whenever I happen to enter a church, I walk around and take the time to look at the windows and art that adorn it, even if it wasn’t decorated by Nincheri. I used to only have that state of mind when I visited Europe. I travelled to the UK, Paris, Austria, and Italy, and I would make it a point to visit their historic churches, but whenever I went to a church here – for a wedding, a funeral, a christening – I never looked around. Granted, some churches were never elaborately decorated in that way or were whitewashed in the 60s, but now I look, I examine. Another takeaway for me is a deeper understanding of the art of stained-glass windows. It’s always been considered a lower art and I never really bothered looking at windows, aside from scanning them, but now I know all the work that goes into them; all the decisions that need to be made; all the precision, skill, and artistry required, and I can better appreciate the results. I remember visiting a church in Galway, Ireland, a few years ago, as I was writing the book, and looking at a window that represented William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World. In it, a piece of lead slashed across Jesus’s robe in a very, very displeasing way and I thought: “Oh, Guido wouldn’t have accepted that kind of work!” In a way, for bad or good, he defined my sense of aesthetics.

LC: With all the information that you’ve collected, you had to make very definitive choices about what to include and what to leave out. Do you have any thoughts about a second volume on the topic? Any ideas about putting on an exhibit or giving talks about Guido Nincheri? A virtual museum or website?

MG: Nincheri has become a lifelong project for me. I don’t know if another book is in the cards, but if one is needed I wouldn’t be opposed to writing it. At the moment, Roger Boccini Nincheri is giving church tours and talks on his grandfather, and I may take over at one point. In the meantime, I’m helping him analyze his grandfather’s art and write about it. Last spring, we wrote a booklet on Madonna della Difesa that can be purchased at the church. I have a feeling we’ll be writing more of those. I’ve also created a website (guidonincheri.ca), which, I hope, in time, will become a kind of database of his art. mRb

Author photo by Terrence Byrnes

I loved this guy’s work at my childhood church of St. Anthony’s in Ottawa, despite the fact I didn’t have a clue who he was.

Guido Nincheri was my great grand-father. I live in Italy, and just a few months ago, in my attic, I found out many letters and photos between Guido Nincheri and his first Italian daughter, Renata. She was my grand-mother.

I do not understand why the Guido Nincheri’s Biography does not talk about her.

The letters show the love between father and daughter and talk about Guido Nincheri experiences in Canada. The photos show Guido Nincheri and his new family, his brother and the catholic priest grandson.

I would like to organize a trip to Montreal to visit the Guido Nincheri Museam.

Maybe next year.

Barbara

I have a photo of a drawing by Guido Nincheri. It is of my grandfather, who I think was a guard at the interment camp at Petawawa. It is dated Sept. 1940, in Roman numerals, which seems to conflict with the reported incarceration date, 1942, of Mr. Nincheri.