A friend once asked T. S. Eliot whether he agreed with the view that most editors are failed writers. Eliot is said to have replied, “I suppose so, but so are most writers.” Happily that’s not the case with Montreal’s Peter Kirby whose debut novel, The Dead of Winter, recently hit the bookstores and shows every sign of being around for a while.

Kirby, a lawyer with one of Canada’s largest firms, skilfully draws on his experience to tell the tale of five homeless people murdered on the streets of Montreal on Christmas Eve. The crimes threaten to dominate the media, and Inspector Luc Vanier’s Chief is anxious to solve the cases quickly. But before the investigation is brought to a conclusion, it takes unexpected turns, reaching into the upper echelons of Montreal’s movers and shakers, and Vanier’s own life is put on the line.

I recently met with the new author over a pint and a pie at one of Montreal’s watering holes.

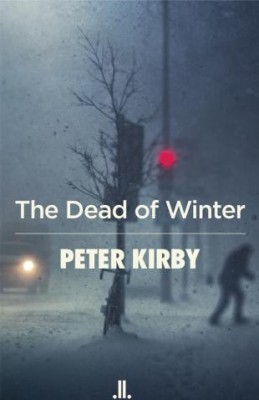

The Dead of Winter

Peter Kirby

Linda Leith Publishing

$21.95

paper

324pp

978-0-9879-9462-2

Peter Kirby: I love being a lawyer, and I love litigation. It’s a challenging job and I’m not changing it anytime soon. But creativity in the law isn’t the same as creativity in writing. If a judge leans back in his chair, looks you in the eye and says, “that’s a very creative argument,” you’re in trouble; it’s time to pack up and go home. Writing fiction has always been a creative outlet for me. But for the longest time I was just dabbling, stopping at first or second drafts and moving on. Then I decided to get serious and the more I did that, the more I enjoyed it. Changing the level of focus gave me a whole new level of satisfaction; it changed me.

JN: The Dead of Winter is a convincing, but grim, tale. How did you pick this subject?

PK: The easy answer is that I was in a grim mood and wanted a grim subject. The real answer is that there’s a lot out there to be grim about and I wanted to engage readers with more than a straightforward whodunit. Homelessness, poverty, mental illness, and the abuse of authority are all things we witness too often and do our best to ignore. In The Dead of Winter, the homeless and the disenfranchised are not there as props for the story; I want the reader to think about them.

JN: The Dead of Winter is very believable, especially the bits about the shelters and the street life of the homeless. How involved did you get in the research? Did you visit shelters and talk to the homeless? Given that many street people are suspicious of strangers, was that difficult to accomplish?

PK: This isn’t Down and Out in Paris and London. Most of the research was traditional: reading, watching, and listening. You can get someone to talk to you by handing them $5 and asking how it’s going. But the best talkers are usually the ones who have the best handle on street life. The articulate ones rarely sleep outside in minus 20; they find shelter, it’s the mentally ill or the severely addicted that end up out in the cold, and they’re harder to talk to.

JN: Your protagonist, Luc Vanier, flirts with alcoholism, is estranged from his wife, and doesn’t really get along with his boss. Would you say he’s an anti- hero in the classic hardboiled crime fiction tradition?

PK: I’m not sure that anti-hero is the right description. I prefer to think of him as an ordinary guy that’s doing his best in some trying circumstances. He’s a complicated guy, but I hope that readers will understand his struggles. And besides, straightforward isn’t that interesting. Imagine a guy walking along the edge of a cliff, looking at the sea, before he goes home to supper with the wife and a couple of hours of television. That’s pretty boring. What if he slips off the cliff and you watch his quick descent to the rocks and cold waves? A little more interesting, but not much. But what if, on the way down, he’s clutching desperately at branches, the shrubs pulling out from the cliff face and releasing him to fall again, his hands clutching at everything as he falls? Now, it’s getting interesting. If Vanier is falling, he will be clutching at every branch on the way down. I admit, Luc Vanier is not perfect, but he’s a good man with a good heart who’s weighed down by some imperfections. He’s flawed, but he’s aware of his flaws and sometimes tries to correct them. decent person, loves his mother, is kind to children, and worries about good people getting hurt. He’s human, that’s all, not an anti-hero. So, if his trajectory off the cliff is apparent to every reader, I want the readers to cheer for every branch that slows his descent. Who knows? Maybe one of the shrubs will hold and he’ll save himself. And, as for questioning authority, Vanier doesn’t take much to authority. Anyone who doesn’t question authority on a regular basis is either in a position of authority or a slave. Questioning authority is a muscle that needs to be exercised on a regular basis.

JN: The characters are varied, interesting, and believable; the action in The Dead of Winter is very well paced. Do you see it as ripe for a film treatment? Have there been any feelers so far?

PK: Do I think it would make a good film? Sure, I do. And I don’t think there are enough Montreal crime films. This city is cinematic heaven for dark crime stories. Will Ferguson said that it would make a great film, and who am I to argue with him? My publisher Linda Leith has received at least one enquiry about optioning the rights. We’ll see what happens.

JN: Returning to the book, what lies in store for Luc Vanier? Is there a sequel in the works?

PK: Vanier is going to be around for a while because I have a lot more pain to inflict on him, and the second book is well underway. Vanier investigates the “exhibition” murder of a local drug dealer found hanging from a tree in the street. But nobody seems to care. The novel explores what might happen if ex-soldiers formed a community organization in Hochelaga, to fill the gaps left by government cutbacks and disinterest, then moved to clean up, and control, the neighbourhood. Drug dealers, pimps, and prostitutes would be cleared out, sometimes violently, but who would care? And, if nobody cares for long enough, how much power could they accumulate? And when would it be too late to move against them? mRb

0 Comments