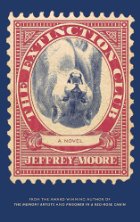

The Extinction Club

Jeffrey Moore

Hamish Hamilton

$32.00

cloth

368pp

9780670063954

These people belong perfectly in St-Davnet-des-Monts, a fictional Laurentian town named for the patron saint of – you guessed it – the mentally disturbed. The looniness of this town serves as the perfect backdrop for Moore’s quirky eco-thriller.

The narrative centres on Nile Nightingale, who has driven up to St-Davnet from New Jersey hoping to escape the law, multiple addictions, and memories from his life as a ne’er-do-well. The town’s deconsecrated church seems like the perfect refuge, but, on his first visit, Nile witnesses an unidentifiable object being dumped in the cemetery next door. On further investigation, he discovers the wounded body of Céleste Jonquères, the teenaged activist. From that moment on, Nile is sucked into a world of poachers who will do anything to be rid of people who get in the way of their business: selling parts of bears and other endangered animals. What ensues is a funny adventure about the screwed-up Nile Nightingale and Celeste J. who team up to try to outwit these shotgun-toting goons.

The wacky Québécois setting in which these characters doggedly pursue the bad guys allows Moore to combine humour with menace. But the author’s political agenda is a distraction: many of the sections narrated by Céleste read less like a novel than a pamphlet for PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals). This message is present in Nile’s chapters too.

For example, as Nile sneaks across the Canadian border, he meets up with two illegal Chinese immigrants. They walk together for a while, conversing in Mandarin (which Nile learned during the year he spent in Shanghai – of course). This chance encounter and the intimacy that creeps into the strangers’ conversation as they walk along a dark country road is mysterious and evocative. Yet the mood quickly shifts from the personal to the political when Moore suggests that Nile’s new acquaintances are really entering the country to work in the bear-poaching industry. Moore creates a plausible human interaction – the pleasure to be had in a surprise meeting between strangers in an unlikely place – and then hijacks the scene with his political message.

The plight of endangered animals that are being poached to extinction is an important issue, and Moore’s cause is a good one, but it’s out of place in a novel. By forcing his message into his characters’ every thought and encounter, Moore makes too clear a distinction between good and evil.

In interviews, Moore has listed Philip Roth and J.M. Coetzee as two of his favourite writers, but the moral and emotional ambiguity that characterizes their writing is nowhere to be found here. The Extinction Club is a fun romp in the Laurentians – and surely a distracting summer read by the lake. But despite the colourful universe he creates, Moore introduces the interesting conjunction between species extinction and insanity without doing justice to either one. mRb

0 Comments