“Dalie Giroux is a political theorist who cares for semi-retired hens,” translator Jennifer Henderson tells us in her introduction to The Eye of the Master, a hybrid of political thought and personal essay first published to acclaim in French in 2020. The image speaks volumes: Giroux is an erudite thinker with earth on her hands. Her method is to patiently layer strata of materials ranging from historical scholarship and literature to family photos and personal memories, in a slow and organic process that fertilizes her cogent, militant thought and clear, keen prose.

As the post-referendum identitarian nationalist turn in Quebec politics has grown increasingly strident, Giroux’s voice has been one of many raised in opposition to ask uncomfortable questions, including the one central to Quebec, Canada, and other postcolonial states: By what right do we occupy, and dominate, the lands we have settled? And by what imaginative processes have we legitimated this domination?

These big questions are explored (not patly answered) in six long-form hybrid essays in two sections, “Politics” and “Narratives,” bookended by a helpful introduction and a “Conclusion in Erratic Blocs,” hopeful fragments arranged for the reader to assemble into meaning.

The Eye of the Master McGill-Queen's University Press

Figures of the Québécois Colonial Imaginary

Dalie Giroux

Translated by Jennifer Henderson

$29.95

cloth

184pp

9780228016373

One vital distinction is that, even if Quebecers might lay historical claim to the St. Lawrence Valley based on long habitation, no such claim could be made to Northern Quebec, home to the province’s hydroelectric and mineral wealth whose resource exploitation is the “linchpin” of the modern settler colonial process. Like Alberta’s oil, Québec’s hydroelectricity ushered in modernity and prosperity. But any claims to rights over northern territories are based on British constitutional law. Giroux quotes Inuk thinker and leader Zebedee Nungak:

No one would question the “masters” part of the slogan if the frontiers of Quebec delimited the places where the descendants of Champlain lived and worked the land in order to maintain and nourish their distinct French identity, their language, and culture… The problem is with the “our own house” part, which has come to encompass Eeyou Istchee (Cree territory) and Inuit Nunangat, great swathes of territory with not one ounce of French history or language or culture.

Giroux challenges the “presumption woven through the received narrative of Québécois national liberation that suggests that today’s francophone Québécois, descended from an ‘original French colonial population,’ should inherit the French colonial prerogative that was appropriated with the British ‘Conquest.’” Since the 1995 referendum defeat, stripped of the goal of independence with its lofty, hopeful grandeur, we have seen successive governments of all political parties, abetted by corporate media, exploit resentment and this “colonial presumption” to make increasingly petty and punitive policies focused on mean-spirited projects of dubious relevance, from the “Charter of Values” to banning hijab-wearing women from the public service to protecting the right of educators to voice racial slurs in the classroom.

Though these measures often seem untethered from objective reality – they respond to fabricated problems in no way apparent in the streets and workplaces of Quebec City or Montreal – they nevertheless dominate airwaves and elections while pressing concerns, from climate change to the housing crisis, are all but ignored.

To free ourselves from this vicious cycle, Dalie Giroux proposes a twofold process. “Foregrounding Indigenous territoriality” and engaging with Indigenous thought will help us understand Quebec history more honestly and fruitfully. Only then can we begin working to break the chains of “mastery” that determine relationships in every sphere in order to “live without a master, collectively, in a sustainable way.” As Richard Desjardins, who grew up in a mining town, sings poignantly in his cover of “The Ballad of the Millwheel,” “We don’t want a new master, we want all mastery ended.”

Other essays in “Politics” examine how in the 1960s and 1970s, Quebec’s ostensibly decolonial nationalist movement could have so largely ignored Indigenous claims and co-opted the discourse of Black liberation, yet stopped short of truly putting other peoples on equal footing once power was attained. Giroux quotes the ever-lucid Emilie Nicolas:

Having deployed ‘white n—’ as a figure for our own struggle and successfully advanced our cause, were we interested in the condition of those who were still racialized? (…) Once we had called ourselves colonized in our own country, stressing our political rights, what did we make of the discourse of Indigenous peoples on their stolen lands?

The personal essays in the second section, “Narratives,” weave together memories and family photos to explore how the broader movements of the time played out in individual and family lives.

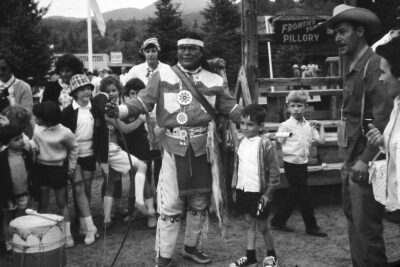

In “A Trip to Frontier Town,” Giroux conjures up the Lévis of her childhood and earlier, delving into her family’s long history in the “maritime blue-collar quarters on either side of the Saint Lawrence (…) A world of workers, artisans, hosteliers, boatmen, habitants, housewives; crocheted curtains, visits by the priest, marriages, baptisms (…) swimming on the south shore, wild strawberries and raspberries in summertime, games along the railway lines…”

A trip to Frontier Town, North Hudson, New York, 1962. Personal archives of Dalie Giroux.

Searching through family photos (reproduced in the book), Giroux lands on one depicting a vacation to “Frontier Town” in North Hudson, New York, where the settler colonial narrative of “Cowboys and Indians” was recreated for tourists – her uncle appears in the picture – much as it was re-enacted in their costumed play as children and in the political theatre of Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau.

Jean Drapeau, mayor of Montreal, greets Frontier Town performers. Photo credit: Jennifer St. Pierre and Tammy Whitty-Brown, Frontier Park Abandoned Theme Park Then and Now (2015).

Having earlier described the contours of settler colonial attitudes, Giroux here shows how settler colonial worldviews are shaped and transmitted, beginning in childhood, by everything from the games we play to the objects in our homes.

This strand is pulled further in “The Paupers of Settler Colonialism,” which retraces her long engagement with Wendat scholar Georges E. Sioui alongside the etymology and usage of a French phrase, le mauvais pauvre. She describes sitting across from Sioui, her university colleague, explaining her position:

as a white Québécoise of colonial ancestry in America (…) I rifle through the past, and I find nothing that can catalyse me: neither a native that would constitute a codex of liberty in this territory, nor a European heritage that could guide me toward a relation to the land other than commodification, expropriation, extraction, accumulation, diversion. The inheritance I need I do not have; the inheritance I have, I do not want.

Sioui’s answer – “You are realizing something important there; you must write about it one day” – makes Giroux realize that “the condition of being without an inheritance is a chance at something.”

Le mauvais pauvre (translated by Henderson as “paupers of settler colonialism”) is explored as a metaphor for the damage a colonial mindset does to its own. Giroux quotes Anishinaabe scholar Aaron Mills: “Settler people harm themselves in founding their political community upon violence, which slowly destroys it from within. So long as they maintain their earth-alienated constitutional order, which treats non-humans as resources to be exploited, there is no escape from this fate.”

What is the value of publishing in English a book written by and for francophone Quebecers to address their specific history and imaginary?

First, the issue of honestly confronting colonial histories and developing new ways of seeing and living in our postcolonial world applies equally to Canada and other states. Specific colonial processes may differ, but the outcomes of cultural erasure and unchecked extractive capitalism have been terribly consistent. Giroux’s project is largely to shout into the wind of denialism that Québec is no exception to this rule; neither is Canada.

Second, Giroux’s combination of academic rigour and probing personal narrative is original and powerful. Translator and editor Henderson deserves credit for tackling such a challenging project in which not only the text itself, but the entire body of literature and cultural reference it is built around, requires translation and explanation for the book’s new audience.

For all the scholarship it contains, this book does not feel academic. I am convinced that Dalie Giroux’s slow, organic engagement with her source materials and manner of embodying scholarly thought in lived experience is more important today than ever before, as we grapple to understand what constitutes human intelligence, what exactly A.I. cannot do. Reading widely over decades; having in-person conversations and serious dialogue based on open, honest listening; testing our ideas scrupulously against our personal experience – by doing these things, we can arrive at an honest account of our history that might one day serve as a foundation for a relationship with our world that will not literally burn it down. (Combustion is the subject of Giroux’s most recent book, Une civilisation de feu, out now in French.) The Eye of the Master is an exhilarating read that gives no easy answers, just hard questions. That’s a good start.mRb

0 Comments