Back in 2016, I spent several hours every night going through the social media posts of a far-right Facebook group called Never Again Canada. I published the names of people who made violent threats against politicians on an anonymous website. After a few months, I lost the password to the website and, relieved, I walked away and never looked back at the thousands of posts I had saved.

While this work was far from mainstream, I wasn’t alone in doing it. There were other digital activists, journalists, and academics doing similar work. But nowhere was there a static reference that researchers could rely on to help keep track of the ever-changing universe of far-right groups.

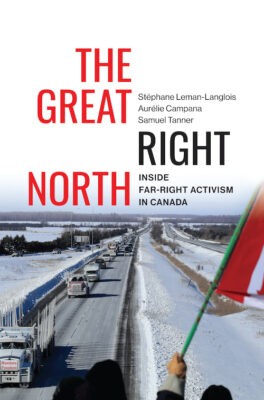

The Great Right North

Inside Far-Right Activism in Canada

Stéphane Leman-Langlois, Aurélie Campana, and Samuel Tanner

McGill-Queen's University Press

$29.95

paper

288pp

9780228022848

Leman-Langlois, Campana, and Tanner dive deep into the far right through a mix of research and interviews with far-right activists. Part encyclopedia, part field guide, the book is academic rather than narrative, and each chapter could be a book all on its own. The interviews give insight into the motivation and choices of those who have chosen to become far-right activists, and a catalogue of active far-right groups explains the difference between Atalante, The Base, Soldiers of Odin, and others.

Crucially, the authors try to answer the million-dollar question: what is to be done about the far right in Canada? They trace the history of policing what Canada considered to be terrorist threats, from state policing agencies’ focus moving from communists to Muslims, and explain that even as the far right has posed a clear threat to Canadians, police have not figured out how to interact with these groups. One issue poses a particularly difficult problem: many of these groups have allies within the police.

The authors admit that there are few options that are known to work to neutralize the far right. They argue that a strong media ecosystem is crucial to grapple with disinformation, something that is basically on the verge of collapse. They warn that the far right will grow in power and influence as mainstream media continues to decline.

The book is dense, and incontournable for understanding the far right as it was in the 2010s. However, the authors don’t try to link the operation of these groups to current affairs. In the absence of talking about broader political forces, especially related to white supremacy and colonization, the authors miss the opportunity to imagine where current far-right rhetoric will lead in mainstream politics.

For example, the connections between the far right’s prominence and the xenophobia of François Legault’s government through various laws since 2018, or before that, with Phillippe Couillard’s obsession with Muslim women, need to be further explored. The far right’s political confidence grew in each of these moments, reminding us that far-right groups rise and fall along with the motions of mainstream politics and economic conditions. After all, it was a tweet from Justin Trudeau welcoming Syrian immigrants to Canada that convinced the Quebec City mosque shooter to abandon his plans to shoot up a mall in Sainte-Foy and instead target the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec.

As academics, the authors try to be as neutral as possible in assessing these groups, a luxury that is only available to white scholars. If there is a flaw in this book, it’s that the perspective of the people who are most harmed by the rise of the far right is absent. Even still, The Great Right North is a vital contribution to our collective understanding of Canada’s far-right ecosystem.mRb

0 Comments