What is happening now, here, to us? The question recurs throughout Melissa Bull’s first collection of short fiction, The Knockoff Eclipse, which could double as an index of quotidian humiliations and indignities. The answer, it seems, requires that we learn to recognize and name injustice where and when it occurs.

Alluringly spare (160 pages contain twenty-three stories), this book doesn’t warn you before it jabs you with a lucid emotional cocktail. Like the nurses in “Number 42” – a story about a pharmaceutical test subject that answered all of my questions about those Medieval Times-themed ads on the metro – this is the kind of fiction that will drive a malleable hose up your arm and get exasperated if your blood coagulates disobediently. What should be a simple procedure – a road trip, a weekend at the lake with family, a conference – becomes chaotic, upsetting, gross.

Take the title character in “Chez Serge,” one half of a depressingly familiar modern non-couple:

He tells her she’s more beautiful in the morning; he coughs phlegm into some toilet paper and roots deep into his nose for a load of dried-up skin and snot. He tells her that one day his nose will rot off his face. He says they should have breakfast. “Did you want to borrow my toothbrush? I promise no other woman has used it.”

Bull takes grim delight in moments like this: normal, though they shouldn’t be; disgusting both emotionally and materially; liable to leave characters and readers both at a loss for the appropriate reaction. Bafflement? Outrage? Should a person shrug it off, or walk out? Should a character quit their job in a boutique where everything is “singularly beautiful” and “a Stelton jug in burnt orange melamine expresses like no other thing the quiddity of the cylinder”? No, quitting doesn’t even occur to them, because they can’t afford an umbrella and their shoes are falling apart as they walk home through a rainstorm. Likewise, will a character listen to the Italian countess slumming in her apartment during the ice storm when she tells her, “It is essential to find your signature scent”? No, because she knows how much a can of spaghetti sauce costs and the countess is decked out in “haphazardly worn Yves Saint Laurent.”

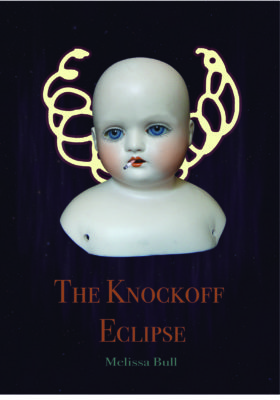

The Knockoff Eclipse

Melissa Bull

Anvil Press

$18.00

paper

160pp

9781772141207

Bull’s eye is unfailingly precise, and the best of these stories distill warped vectors of humanity into dry-ice absurdity and pitiful rawness. This knack for cataloguing unfairness and grubby immobility on every scale, from the macroeconomic to the domestic, makes for addictive reading. Bull’s demotic, unpretentious sentences provoke the simultaneous adrenaline high and depressant low of a drunken argument on the street in front of a pseudo-Irish sports bar with an unmemorable boyfriend. A fight like the one in “Stations of the Cross,” where a young woman takes an inadvertent nostalgia-turned-shame tour of the city she came of age in:

She had no recollection of any words she and her then-boyfriend had exchanged in their clash, she could only recall how she’d felt. And she felt it, palpably, immediately, right now.

This could just as easily describe good fiction’s job: not to express emotion but to evoke it. Or provoke it – if anything, Bull is a master provocateur, working through subtle, overlooked shades of experience to find some new level of exactitude in emotional injury. Like the experience of walking, as a tourist, to sit in a famous square in an unfamiliar city:

You know when you have been had. When you see that you’ve been childish and for a while you just feel shitty about not knowing that you were so stupid—you don’t want to think yourself capable of being so stupid. I don’t want to throw around a word like shame. It’s too punishing. Regret is too nostalgic. I sat there thinking neither of those words, just—I am such an asshole.

“I see a scene and I feel something acutely,” Bull says of her process for writing emotion. “Usually some level of discomfort, either from having to write something new and exploratory, or from whatever situation I’m investigating. I feel the characters’ emotions sharply but prefer to not over-explain them. Their gestures, the things they notice, already feel loaded to me.”

Bull’s debut poetry collection, Rue, came out with Anvil in 2015, and was shortlisted for the Robert Kroetsch Award. She translated Nelly Arcan’s essays Burqa de chair in 2014, and is a prolific French-to-English translator for theatre and print. She says some of the stories in The Knockoff Eclipse were written in internet cafés along Mont-Royal Avenue a decade ago, while others were written as recently as last year.

While the stories aren’t exclusively set in Montreal, many are, and the book is threaded with the city’s idiosyncrasies. As a translator writing bilingual characters in a bilingual city, Bull slips back and forth between francophone and anglophone lenses, often in the same sentence, leaving coded clues for the initiated. Tanks on the street, ice storms (the ice storm), deliberately tired quips about tea and oranges, “Laval-pretty” and “Hochelaga-poor.” Montreal has been inspiring an extensive literary cartography for decades, but Bull’s linguistic overlay refers to a data set many readers in Vancouver, New York, Copenhagen, or Mile End might not otherwise encounter. Her cryptographic details recount the alienating, pleasurable friction of living here, where linguistic or empathetic ambitions never guarantee comprehension.

“I’ve often wished I could write in French, but I don’t think I can,” Bull says. “Yeats said, ‘English is my native language but not my mother tongue.’ French is my mother tongue. For a variety of reasons, my education was primarily conducted in English, and this, added to the fact that my anglophone father had custody of me and was also a writer, and the high-stakes politics in Quebec at the time of my adolescence, probably all acted to shape my writing in English rather than French. So I don’t write in French, and now feel that it would embarrass me to try. And yet I am also a francophone. The words and accents of this place are my home. In my mind, many of these characters are French-speaking, and I am translating their words into English.”

“I think in both languages. I live in both languages. I happen to write in English, but I don’t want to censor myself. I also want to share with English-speaking people a little bit of how things are, here. How things sound to us in French.”

I suspect Bull’s eye for injustice is part of this broader act of translation: even as she generously relays culture and language, she also translates our own gut-level reactions into something recognizable. But, as with all translation projects, there are limits. Certain facets remain unknowable. In “Illumination,” for instance, a youthful road trip would be satisfying for its social intricacies alone, but the plot takes a breathless, bizarre turn that leaves the characters unable to process it. “What happened to us last night?” asks Geneviève. “It wasn’t anything,” Malik responds. The reader might take a guess – I won’t spoil it here – but the story turns the question into an act of necessary resistance. What is happening here, now, to us? Even when the answer eludes translation or transcends comprehension, The Knockoff Eclipse reminds us to keep asking, naming, and affirming our presence. mRb

0 Comments