In the village of Malabourg, girlhood is a difficult, even dangerous time. This fictional town on the Baie des Chaleurs, the setting of Perrine Leblanc’s second novel, is a place out of time, inhabited by generations of lantern-jawed fishermen and run by local gossips. The Lake, translated into English by Lazer Lederhendler, seems at first glance to promise a kind of thriller, but its village setting is the stuff of contes or legends.

The girls of Malabourg become women under the eyes of the village patriarchs, who are apparently, to a man, intoxicated by their developing forms. “The men of the village, with their fishermen’s faces and ageless palms, are driven to distraction by the girls of the new generation.” Here, a body is something thrust upon a girl; her “precocious fertility [drops] like a guillotine blade on her little girl’s neck.” And the men are not to be held responsible for their desires: “in Malabourg, it’s always the girls’ fault.” But when a young woman goes missing and turns up dead, discovered at the bottom of the lake that the children of the village will later dub “the Tomb,” only to be followed by two more girls, the village is shaken. These events would seem to set us off on the trail of a mystery, but this is a crime all too quickly solved, the answers brutally ordinary. It will later be referred to in the village histories as a “calamity,” a “small hurricane,” something wrought upon the passive community rather than deliberate violence enacted by one man.

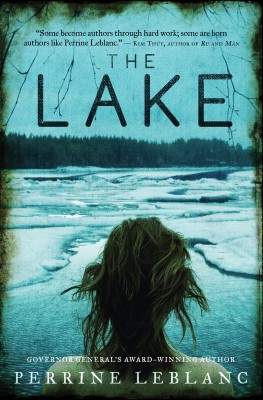

The Lake

Perrine Leblanc

Translated by Lazer Lederhendler

House of Anansi Press

$22.95

paper

208pp

9781487000202

The novel is at its best in the sections set in Malabourg, where the narrative meanders through a cast of small-town characters: Madame Ka, an “amiable old whore”; Barry O’Reilly, a Frenglish-speaking, easy-going drunk; and Cécile, Mina’s Mi’kmaq grandmother, who concocts herbal teas and remedies. Later sections of the novel, in which Mina and Alexis meet again in Montreal in the midst of the 2012 printemps érable, are an abrupt, even jarring return to reality. There still seems to be so much more to say back in the village. As a contrast, I was reminded of Elisabeth de Mariaffi’s excellent and sensitive exploration in The Devil You Know of the way one continues to live in the aftermath of this kind of violence, even after the crime has been “solved.” Mina and Alexis have good reason to move on, but by now the village itself is perhaps the character with which we are most engaged. What does a changed Malabourg look like? When will its women stop looking over their shoulders?

Leblanc’s sensual language is beautifully rendered in Lederhendler’s translation, though I did wonder at the choice to “translate” the title – the original title, Malabourg, could work in English too, and is far more evocative of the world of Leblanc’s story than the starker The Lake. As Cécile tells her granddaughter, urging her to leave, “the malady is in the name of the place.” mRb

0 Comments