During the 1995 referendum on Quebec sovereignty, Chantal Hébert, one of Canada’s most popular political pundits, moved her family from Ontario to Quebec. Ironically, the decision had nothing to do with politics.

“I spent the referendum taking my younger son to entrance exams for high school in Montreal,” she explains on a cold, bright January morning in Montreal, the city she continues to call home. “I didn’t want my sons to be Ottawa people. I wanted them to be in a place where there were four universities.”

For a woman who has devoted the last forty years to discussing national politics on air and in print, Hébert seems surprisingly dispassionate. The Morning After, her fascinating new book about the 1995 Quebec referendum, contains not a whisper of her own political views.

She is sixty years old, although the smiling woman sitting across the table from me seems younger. Perhaps it’s the jeans she’s wearing, or the absence of make-up. Or perhaps it’s the curiosity and the glint of humour in her eye. She belongs to the baby boomer generation, which has been the heart and soul of the Quebec sovereignty movement since the 1960s. In her approach to that issue, however, she defies generational stereotypes.

“I’ve covered a lot of constitutional stuff,” she says, “and I have to say, the bigger the story, the less I’m invested in it. That’s the way we are trained as journalists. You cover a good story, but it’s not a story in which I’m the main character.”

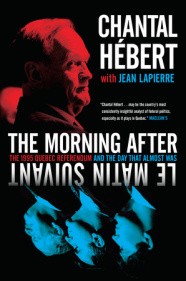

The Morning After

The 1995 Quebec Referendum and the Day that Almost Was

Chantal Hébert, with Jean Lapierre

Knopf Canada

$29.95

cloth

320pp

978-0-345-80762-5c

But here’s the kicker. Instead of requesting a rehash of actual events, Hébert (with help from former Liberal and Bloc MP Jean Lapierre) asks her subjects what they would have done had the Yes side won.

Why, I ask, did she decide to write about the referendum twenty years after the fact?

“These people have never told their story,” she replies. “There weren’t many referendum books by the main players. I thought, before they disappear and their voice becomes what other people make of them, I’m going to … ask them to tell me how they imagined the nine-o’clock news that night, if [Société Radio-Canada news anchor] Bernard Derome announced the Yes had won.”

Parizeau is eighty-four years old today; Chrétien is eighty-one, and Bouchard is in his mid-seventies. The book is a time capsule. The revelations it contains, however, puncture time-worn myths.

The No camp offered Hébert few surprises. She had expected divergent views concerning what to do in the event of a Yes victory. She had also guessed correctly that the people in Quebec would be at loggerheads with Jean Chrétien in Ottawa, and that the rest of Canada would skirmish over conflicting local interests.

What Hébert found astonishing was the level of chaos in the Yes camp. It was common knowledge that Bloc Québécois leader Lucien Bouchard was more cautious about secession than Premier Parizeau. Even so, Hébert was surprised at how fundamentally they disagreed about what a Yes victory would have actually meant. Even more disconcerting was that the two Yes leaders showed so “little inclination to talk to each other about the way forward.” On the day of the referendum, Parizeau refused to take any of Bouchard’s calls and left his so-called “Negotiator-in-Chief” on his own to watch the results come in. Bouchard admits that when the final result was announced, he was completely in the dark as to Parizeau’s plans.

Yet, according to Hébert, Parizeau was “possibly the only adult in the room.” He was, she says, the only one in the Yes camp “who seemed to have been thinking about the reality of creating a country.”

Unlike Bouchard, whom Hébert refers to in the book as a “paper tiger,” and youthful Mario Dumont, Parizeau had tried to imagine the reactions of the rest of Canada after a Yes victory. He foresaw (rightly, in Hébert’s view) that the other provinces would be disinclined to negotiate with Quebec beyond the barest minimum. Bouchard, with his visions of deals and partnerships between the provinces, was dreaming in colour.

One of the most compelling sections of the book features interviews with political figures from outside Quebec and Ottawa – Roy Romanow and Preston Manning from the West; Frank McKenna from the East. The ballots may have been cast in Quebec, but Hébert reminds us that lives outside its borders would have been affected.

By including these stories, Hébert takes a swing at a misconception she’s fought against all her life as a journalist: “that the Rest of Canada is a monolith.”

Hébert’s openness to the full spectrum of opinion in this country permeates The Morning After. Perhaps her training as a journalist explains this openness. Or perhaps it’s the result of the many years she lived, studied, and worked outside Quebec. When I ask her to describe her own identity, her answer is an eye-opener: “I’m a Montrealer. I’m an Ontarian.”

She seems at ease with the contradiction, belonging to the minority of her generation who straddle Canada’s official languages. She may live in Montreal, but her principal employer is the Toronto Star, for which she writes a weekly column in English. She’s a national affairs panellist on CBC television with Peter Mansbridge. She also writes guest columns for L’actualité and is heard five days a week on French-language radio in Montreal.

Canada did, in the end, survive the referendum of October 30, 1995. But it was not a happy ending for anyone involved. The Yes side, which lost by only 0.58% of the total vote, was devastated. Premier Parizeau, whose lifelong dream had been to create a sovereign Quebec, resigned the morning after. But the No side did not celebrate either. “There was no embrace of Canada in that result,” Hébert remembers. “It wasn’t a commitment.”

Much has changed since 1995, and even since 2012 when Hébert conducted the interviews for the book. In last spring’s election, the Parti Québécois under Pauline Marois suffered such a spectacular rout that people wondered if the sovereignty issue was dead.

Hébert pauses when I put the question to her. “Sovereignty is a powerful idea,” she says at last. “I am not someone who believes the end of history is the end of my own era. I would find it very presumptuous to say that in twenty years, in some landscape that I can’t imagine, this idea won’t come back. But I believe that as we have known it, and for my generation, we are not going to be revisiting the issue of Quebec’s future within Canada unless there is a dramatic change.”

It’s a careful answer. I press further, inquiring what Hébert herself would have done the morning after a Yes win in Quebec. I’m angling here, still trying to get at her politics, at the sensibility under the journalist’s skin.

She refuses the bait. “I would have covered the biggest story of my life,” she says, smiling. “It’s probably why I wrote the book. It’s the big fish that got away.” mRb

0 Comments