Anumber of words come to mind while reading Bertrand Laverdure’s newest novel in English translation, The Neptune Room: beautiful, messy, morbid, poetic, and, at times, problematic. Like the two other Laverdure novels released by Book*hug, Universal Bureau of Copyrights (2014) and Readopolis (2017), The Neptune Room is a frenetic read, bursting with cultural, political, and philosophical references. Unlike these other works, a veil of devastation enshrouds nearly every character populating its world. Ninelle Côté, Eric Berthiaume, and their young daughter, Sandrine, form the familial nucleus of the novel, torn apart by an unrelenting series of tragedies. And while the plot follows a fragmented course, jumping decades into the past and future from one chapter to the next, Laverdure’s thematic fixations progress in an arrow-straight trajectory, eventually overwhelming the narrative in a baffling, surrealistic finale.

This is a novel of ideas. Big ideas. Ideas that jostle together and build upon one another, forming the patchwork edifice of what could be called an atheistic spirit-vision of existence. What this vision lacks in coherence, it makes up for in scope. Obsessed with death, identity, free will, and evolution, the (never-identified) narrator delves ever deeper into the dynamic interconnection between the body, mind and emotions, peppering the text with profound statements, such as “We don’t have any brilliant answers to a reason for life, and our inner theatre imagines a choreography of loopholes that drug our perception,” or, “As soon as we have the idea that we will decide what will happen, our body has already beaten us to it.” Laverdure’s sprawling theory of being, although resolutely anti-capitalist, is not bound to any political affiliation. This is especially true with regard to notions of identity, expressed by such pronouncements as: “Our acute desire to determine who we are prevents us from truly seeing life,” and, “to live first means to see, not to define oneself.”

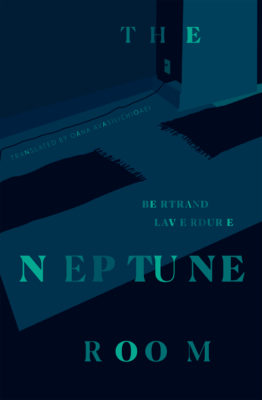

The Neptune Room

Bertrand Laverdure

Translated by Oana Avasilichioaei

Book*hug Press

$20.00

paper

214pp

9781771665810

Oana Avasilichioaei does a masterful job of translating the poetic language and tone of the text. Her creative use of the of the pronouns s/he, hir, hirself, e, em, and eir when representing Tiresias while in a state of flux is especially inspired. Regardless of the novel’s elevated language, reading a book so steeped in suffering and death during a global pandemic, when one’s demise could be a single human interaction away, can make The Neptune Room even more emotionally taxing than it already is. Not everyone will have the fortitude to descend to the harrowing depths to which Laverdure wishes to take them. But the frequent moments of beauty and insight should be more than capable of illuminating the way. mRb

Exceptional review; enticing me to read this novel.