Friedrich Nietzsche once famously wrote, “Without music, life would be a mistake,” and Harry Abley – organist, choirmaster, conductor, and music teacher – might agree. The Organist: Fugues, Fatherhood, and a Fragile Mind, written by Mark Abley, his son, is a love letter, a eulogy of sorts, to a misunderstood musician, and a valedictory tribute to a bygone era. It’s also a history lesson on a supreme form of music aligned with J. S. Bach and the greatest cathedrals of the Romantic era.

In writing The Organist, Abley has opened a window into a musical instrument most of us know little about, and I came away from it with the urge to watch an organ recital up close instead of in a church pew, removed from the physicality of the performance. The sophisticated coordination of the brain, both hands, both feet, and a balanced torso must align to achieve acoustic perfection. An organist in the thrall of performance can feel the vibrations in his entire body. The gift is in communicating those vibrations to the audience.

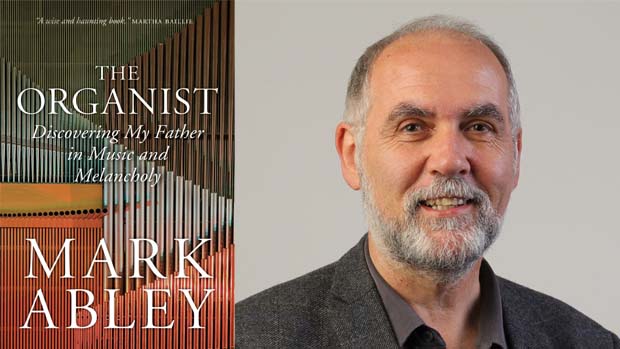

This book, which reads like the very best narrative non-fiction, is brave and heartfelt, surely written from a corner of the soul that demands brutal honesty. Abley, a masterful writer and storyteller, a Guggenheim Fellow, and a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University, rendered this memoir with concise prose, a testament to his first literary love: poetry. Abley is a prolific journalist and writer of non-fiction, children’s books, poetry, and essays, but The Organist is his most finely wrought, a camera lens in sharp focus that dares to unveil the truth about a man who remained a stranger to his son until the day of his death in1994, in Montreal. He writes, “As my father lay dying, I found myself consciously storing up memories, adding to them almost obsessively in the certain knowledge that the subtraction would soon begin.”

The Organist

Fugues, Fatherhood, and a Fragile Mind

Mark Abley

University of Regina Press

$24.95

cloth

312pp

9780889775817

The book unfurls like a flower that blooms by day and shuts down in the night. A dark discontent was at the heart of Harry, who also had two versions of himself. Hidden behind the life of an accomplished musician – whose language of love was composition and performance – was anger, gruffness, depression, and tortured silence. To his young son, that dichotomy created an ocean of distance spawning feelings of injustice. For five decades, his father inched up the ladder as a performer, composer, and teacher, never aiming for riches; instead, he clambered for recognition. Abley’s powerful prose shows how a dearth of praise sent his father’s mind to the dark depths of despair, despite a wealth of talent. Ironically, it was his humility, a quiet ego that refused to trumpet personal success, that converted disappointment into the black coal of inner conflict.

The Ableys criss-crossed the Atlantic four times so Harry could find an elixir that would flesh out his purpose and keep the black dog of depression from finding his way home. He worked the longest at St. John’s Cathedral in Saskatoon, but travelled overseas for gigs in Berlin, Stuttgart, and Bremen, world-class cities that attracted big-name musicians. Music was the salve to every wound, a fail-safe against flagging morale.

On an icy January afternoon, Abley and I sit near the window in a quiet café close to the offices of McGill-Queen’s University Press, where he works as an acquisitions editor. He has a penetrating gaze, as though he has seen too much, and he has certainly inherited his father’s humility. Over a cup of coffee, he tells me about Mary, his mother.

Mary kept two letters in an inner compartment of her purse for sixty- seven years, both written in 1945, weeks after her and Harry’s wedding. “Darling,” they began. His father was, to Abley’s amazement, desperately in love. Perhaps his mother read them when overt expressions of endearment were harder to come by. When Abley came upon those poignant love letters and found testimonials from students expressing their gratitude, he found himself confounded by the contradiction. Who was this man who had profoundly influenced the careers of other musicians? Who was this sentimental person who had saved a white license plate with three green letters and three green numbers, indicating his appreciation for the province of Saskatchewan, yet who often grieved at home, sullen and torn apart by not reaching his self-defined personal heights? “My father dealt with grudges by nursing them tenderly, and venting them bitterly,” Abley writes, later adding that, “The shadow that my father cast was one of misery and frustration.” Always, his father’s face-off was with himself.

Abley told me that writing the memoir was therapeutic, and went a great distance in relieving a life-long burden: “I had a painful childhood, but I no longer feel bruised.” He confesses that aspects of this book – his father’s anti-Semitism, the toll on mother and son, Harry’s mental anguish – would have mortified his mother. If she were alive, she would view Abley’s honesty as an act of betrayal. “Her tribute would have been sanitized.”

When I point out what I saw as the only flaw in the book, that his mother was overly idealized, rendered too perfectly, Abley countered. At age nine or ten, after his father walked out on his family, his mother, desperate and afraid, said to her sensitive son, “You’re more of a man now than he’ll ever be.” The couple reconciled, but as Abley told me, her chilling words signified a shift in duty. From that moment on, he was to walk in his father’s shoes, an unbearable weight for an only child. “I felt responsible for my mother’s happiness,” he says.

The thesis of this finely tuned narrative is that music is redemption from times of great distress. “I’m sure my father loved his family. But love can’t always overcome despair,” Abley writes. Music was the sole source of Harry’s tenacity, a solitary pursuit tinged with self-absorption. Abley would not follow his father into a career as a musician. The intersection of father and son seemed not to have a bridge. Or so Abley thought. Both men have created great works from the end of a pen, albeit with different results: music composition and literature. How did they only see their differences? In the writing, Abley took his time to unveil his father’s mental illness, first establishing the music that fueled a lifetime of passion for Harry. Perhaps it’s a metaphor for the author’s own late understanding of his father’s true nature.

It has taken the author twenty-five years to write this book, although he wrote the first 20,000 words in 1997, at a writer’s retreat in Banff, three years after his father’s death, when raw memories were fuel for interpretation and introspection.

It is a book that is poignant for its truth telling. Anyone interested in the juncture of mental illness and the healing powers of music will find this book irresistible. I can’t tip my hand about the ending other than to say that I lay about for hours with tears streaming down my cheeks, wishing to have known this man called Henry T. Abley. This book is a profound family legacy, for Harry loved Bach, he loved Mary, and he loved his only son. Music is an act of listening. It took hindsight, but Abley now hears his father’s song. mRb

0 Comments