Judith Cowan is a nationally recognized translator and writer. Not only was she a finalist for the John Glassco Translation Prize in 1988, and her book of short stories, More Than Life Itself, shortlisted for the QWF First Book Award in 1998, but she also won the Governor General’s Award for translation in 2004.

Her memoir, The Permanent Nature of Everything, is a reflection on her early years from birth until her first year of high school. It also involves a great deal of historical excavation, an attempt at uncovering the lives of her parents and grandparents. The epigraph on the book’s flyleaf, an excerpt from a poem by Yves Boisvert, speaks of life’s curves and their effect on making us who we are. It is revealed early on that the most significant curves in the writer’s life were her mother’s struggles with her father and with the world. In fact, they were so significant that Cowan couldn’t write her memoir until her mother, Alice, had passed away.

The Permanent Nature of Everything

A Memoir

Judith Cowan

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$34.95

cloth

340 pp

9780773543997

Overall, The Permanent Nature of Everything describes neither a life experience that is representative of her generation, nor one that is so much at odds with the norms and values of her society that readers would feel compelled to turn the pages just to find out what else could possibly happen to the narrator.

Cowan’s upbringing was unconventional and unpredictably quirky, but not because of anything Cowan herself did. Her father Bert – his children never called him Daddy – worked the night shift at the CBC and was rarely awake when the children were. Housework was unheard of, and clothes were left in dirty piles wherever they fell. When the young Judith Cowan had tantrums, Alice would press her hand over her daughter’s mouth until the child turned purple.

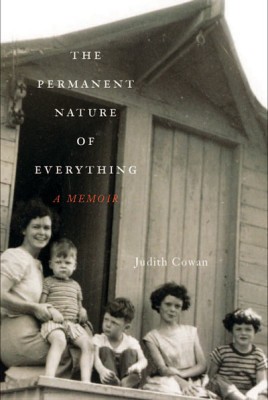

There is a compelling narrative here, but ultimately it is not the story of Judith Cowan’s life that holds the reader’s attention. Instead it is the story of her mother’s life that leaps off the page and captures the imagination. Born in China to shamed missionaries, Alice Cowan (née Leonard) was a strong and self-sufficient woman who neglected her children and didn’t apologize for it. Throughout the memoir, and in the photographs included in the book, Cowan’s mother pulls us in. Beautiful, accomplished, cruel, and demanding, a renegade and a bohemian in an age when most housewives were encouraged to be seen and not heard, Alice Cowan, as well as her battles with her parents, her husband, and the world at large, keep the reader enthralled from beginning to end.

Perhaps one day Judith Cowan will turn the spotlight on her mother’s life and fully explore the history of the maternal curve that formed her. That is a story that deserves a memoir of its own. mRb

0 Comments