Readers make good detectives. Reading always involves finding clues and solving riddles. The detective-protagonist of Cathon’s graphic novel The Pineapples of Wrath is a bibliophile named Marie-Plum Porter. A young woman who lives alone with her goldfish Poopsi, she tends bar by day. By night, she reads pulp fiction to escape her humdrum life. When her neighbour is found dead from what seems to be an overdose of piña coladas, Marie-Plum puts the sleuthing skills she gleaned from devouring crime novels to use solving a string of murders in her town of Trois-Rivières, Quebec.

In this tongue-in-cheek black comedy, reading is a matter of life or death. In one gag, a soon-to-be murder victim calls Marie-Plum for help. His emergency turns out to be his desperation to borrow the next book in a series of detective novels; he’s dying to know what happens next. Another running joke is that Marie-Plum’s mundane surroundings are actually stranger than fiction. She finds it perfectly boring that she lives in an alternate-reality Trois-Rivières that’s home to “the world’s largest Hawaiian neighbourhood.” In this universe, hippie surfers, grinning beluga whales, and even a Loch Ness Monster frolic in the waters of a beach-lined St. Lawrence River.

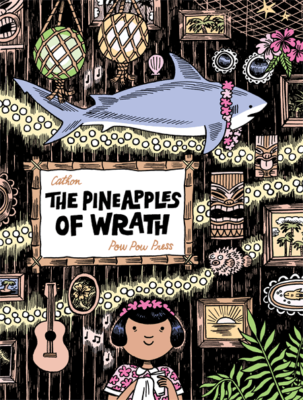

The Pineapples of Wrath

Cathon

Translated by Robin Land and Helge Dascher

Pow Pow Press

$22.96

paper

136pp

9782924049518

Born in Quebec City, Catherine Lamontagne-Drolet moved to Montreal in2010 to study visual arts at the Université du Québec à Montréal. “Trois-Rivières is halfway between those two cities,” she says. “I’ve been driving past it without ever visiting it for a while. I wanted a mix between a real city and an imaginary city.”

It was in Montreal that Lamontagne-Drolet was inspired by a workshop with graphic novelist Jimmy Beaulieu to begin writing illustrated children’s books and graphic novels under the pen name of Cathon. Like The Pineapples of Wrath, many of her other books are unconventional mysteries. With her frequent collaborator Iris, she investigated the mystery of everyday objects in La liste des choses qui existent and its sequel. Her Poppy and Sam series stars a girl-and-panda detective duo.

Cathon employs a range of techniques, from colourful drawings to shaded pencil illustrations. “My style changes a lot from one project to another. My illustration style does not change that much, but the tools I use, yes. That’s what makes a big difference. I like to change technique to vary the moods and the final look of a book,” she says. Panel by panel, Cathon’s visual echoes read like clues. Or are they red herrings? It’s easy to imagine you’re watching a hard-boiled film noir, where the sunset over the St. Lawrence in one panel dissolves into the painting of a sunset hanging in a tiki lounge in the next. Later, the sunset reappears in the form of a hula dancer, haloed by the glow of a log fire. The moody black-and-white graphics allow elements to be reincarnated in other visuals. “For The Pineapples of Wrath, I wanted to become better with pen and India ink, which was relatively new to me, and to learn to create nuanced atmospheres using only black fills and strokes. I thought I would put the comic in colour, but in the end I liked the ‘film noir’ look of the black-and-white pages.”

What film noir, detective novels, and comic books have in common is that they have long been considered low-brow trash. The Pineapples of Wrath is both a fun whodunit comic book and an interrogation of the genre. “I have a fascination for everything kitsch, and that includes tiki. I really like to interest myself in populist places and clichés that everyone knows, to better shift and reinterpret them and do something new. In this case, I wanted to use the tiki culture, but try as much as possible to eliminate the sometimes objectifying and racist aspects of this culture, and to do something more empowering. For example, the only hula dancers in my book do not dance for anyone. They bowl and smoke cigarettes.” Cathon wants to reclaim comic book and genre fiction, too long venues for sexism and racism, of masculine heroes for boys and men. She joins a long line of female crime writers, from Agatha Christie and P.D. James to Quebec’s Louise Penny. She also presents female heroines, villains, victims, and sidekicks. “There must be all kinds, as in real life. We have missed interesting female characters in books and culture in general for so long, and I want to do my little bit to try to compensate for that as much as I can.” The Pineapples of Wrath features a family tree for Marie-Plum that is matrilineal, showing family names passed down through the women.

Translators Helge Dascher and Robin Lang retain this matriarchy in the English-language edition. They even conducted historical research. The protagonist in the original French version is named Marie-Pomme Plourde. “We wanted her name to be as endearing and accessible in English as it is in French, so she became Marie-Plum Porter, with an adapted family tree,” says Dascher. “Trois-Rivières has always been predominantly French, but it has also had an English-speaking population, and Marie-Plum’s hybrid name is a reflection of that history. Robin looked at old census records and made her a descendant of the Porter, Bourassa, and Lapierre families – in the French edition, those names are Plourde, Baril, and Lalancette.”

“I think that the humour of this book is very much based on references,” says Cathon. “References to old detective novels, references to tiki culture and Quebec culture, and references to other kitsch or funny elements, such as the idea of becoming a professional limbo athlete or surfing on the St. Lawrence River.”

Dascher and Lang note “that some of the book’s key references are English (e.g., Agatha Christie, Steinbeck), so there was less bridging to do. Instead, the challenge was to keep the zany feeling of the original. If the book feels a bit off-kilter and endearingly joyful, then it’s true to the French version.”

The title’s nod to Steinbeck was inspired by Working Days, a journal that Steinbeck kept to track and plan his progress as he drafted The Grapes of Wrath. Cathon read it while labouring on her fruit. (This is the kind of goofy, eye-roll-inducing pun you’ll find throughout The Pineapples of Wrath, and that Dascher and Lang were able to retain. For example, a beer named Trois-Ribières becomes Trois-Ribeers.)

Steinbeck’s disciplined writing process was an inspiration. Cathon has long learned her craft by reading books. “I studied visual arts at CEGEP and university, but mostly learned to draw by reading a lot of comics.” She especially loves classics like Peanuts or Moominthat attract adult and young readers alike. And she learned from her beloved Agatha Christie to apply the art of detective work to the art of creation.

“To write a graphic detective novel, I find you have to put yourself into the role of detective,” says Cathon. “You must sprinkle clues here and there throughout the story, then develop how the characters will find these clues during their investigation. When writing my story, I often found I had led myself into a kind of narrative cul-de-sac and had to find a way out. A bit like a detective.” mRb

0 Comments