If The Seated Woman, Clémence Dumas-Côté’s third work of poetry – which takes the form of a stage play – is described on the dust jacket as a “competitive dialogue,” it’s only because its actors can’t seem to agree on their roles. While “the seated woman” wants to get her stage partner, “the poems,” to speak to her, they don’t easily comply. The muse, it seems, has finally refused the conditions of its labour.

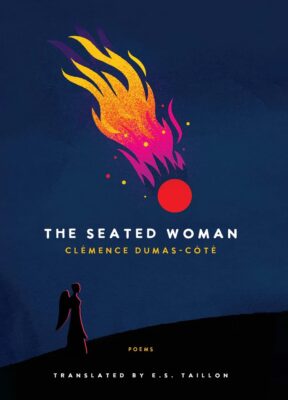

The Seated Woman House of Anansi

Clémence Dumas-Côté

Translated by E.S. Taillon

$22.99

paper

72pp

9781487013295

What makes this a fresh and frankly inspired collection is its unusual, and sometimes surreal use of imagery. Over the span of a few pages, the reader encounters “trampoline rhythms,” “Christmas runoff,” “my irises / and a pile of chewed wrists.” At one point, “the poems” tell the seated woman that “we make love to you, slow like the plague.” The more the poems treat the worn or disgusting areas of bodily and industrial life, the more the concept of poetry comes to resemble them. “On the ground,” observes “the poems” at one point, apparently listing the detritus that surrounds them, “residue of a couplet, origami.”

In The Seated Woman, just as the poems infect the woman’s body, different art forms end up leaching into one another. From theatre to the art of folded paper, the poems show the reader a more porous boundary between poetry and other forms of expression. Perhaps the work’s title is a riposte to anyone foolish enough to call themselves a poet. After all, as the poems remind the seated woman, “You use me to make beehive calligraphy / but what I do is just ventriloquism. / Here, an earthenware vestibule.”mRb

0 Comments