“All the battlements are empty/And the moon is laying low/Yellow roses in the graveyard/Have no time to watch them grow,” croons singer-songwriter Beck in a tune so deliciously dark it makes grieving sound good. Consistent with the rest of his Sea Change album, “Guess I’m Doing Fine” signals the end of a relationship; “the yellow roses” evoke death – or dying love.

The significance of yellow roses is much more hybrid in Greek-Montreal writer Pan Bouyoucas’s latest novel, The Tattoo. When twentysomething-year-old Zoe and her two girlfriends decide to get matching yellow roses tattooed just above their bikini bottoms, their interpretation of the symbol is modern and lighthearted. These young Montrealers see it as a cheery sign of friendship and freedom: “We’ll be the sisterhood of the Yellow Rose—for life.”

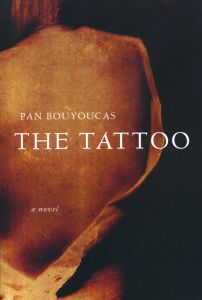

The Tattoo

Pan Bouyoucas

Cormorant Books

$21.00

Paper

240pp

9781897151990

Zoe secretly wishes for a less clichéd tattoo, but she goes along with her girlfriends’ whims, not wanting to offend – a decision she later questions when her bohemian boyfriend teases her for choosing such a “pedestrian” or “conformist” design.

But, one must be careful of what one wishes for. Soon Zoe’s desire for something exotic manifests, but not in a way she ever could have expected – or wanted. She is seriously alarmed when her tattoo magically begins to grow, sprouting magnificently luminous buds. Originally intended to seal a friendship pact, now, much like in Victorian floriography, her yellow rose inspires nothing but jealousy. Suddenly her tattoo is a thorny source of alienation; her friends accuse her of trying to outdo them, and her boyfriend suspects infidelity: “The artist must’ve been quite smitten with you for him to put so much work and love into it,” says Daniel.

Desperate to dwarf her budding bush, Zoe frantically sets out to find help, yet a series of synchronistic events cause her to collide with a myriad of worshippers, all of whom wish to exploit the miracle of her tattoo for their own cause. Each group is convinced that Zoe’s tattoo is the answer to their prayers, a potential solution to major global crises, such as war and climate change. Women living in a feminist colony, for example, are excited about “giving the planet’s unarmed forces the flag they needed to finally overthrow the masculine order that ruled the world.” Consequently, Zoe too begins to believe that her tattoo might be calling her to fulfill a higher destiny.

While skimming serious issues, The Tattoo remains a relatively light, and often humorous, read. Playfully cynical, Bouyoucas pokes fun at the self-serving side of social activism: Zoe is constantly disillusioned when supposedly well-intentioned humanitarians manipulate the media to meet their own selfish demands.

Also mocked is the whole notion of free will. Each time Zoe starts to take her mission seriously, an absurd shift in circumstances sends her plans belly up. Her life resembles a Tarot reading in which the Wheel of Fortune pops up in every hand; thus, potentially profound topics – like memory and dreams – are never thoroughly explored.

Flirting with moral and supernatural themes, the novel has a vaguely mythological feel. Yet Bouyoucas offers none of the obvious moral-of-the-story conclusions of the traditional fable. His cliffhanger ending leaves readers wondering: Are Zoe’s close encounters with death tragic or empowering? And should one, as in Beck’s song, see the yellow rose as a symbol of grief, or, like the activists, as a promise of peace?

Given the general levity of the novel, readers turning the last page may also simply choose not to dig too deeply. For when all is said and done, “a rose is a rose is a rose.” mRb

0 Comments