Poetic language that is dense and rich can be like fruitcake: a fingerling or two is nice with tea, but the going gets rough after the fifth or sixth slice. The Traymore Rooms, a first novel by Montreal poet Norm Sibum, is almost 700 pages. That’s a lot of fruitcake.

Randall Q. Calhoun is an expat American draft-dodger who rents an apartment somewhere in Montreal. The novel is a celebration of the simple yet hyperbolic interactions Q has with neighbours in his humble apartment block and at the nearby café where they all meet to drink. Steinbeck used such everyday settings for simple yet dynamic stories. This novel is about the daily interactions between five to seven people in one of two settings. It certainly emphasizes quotidian complexity, but it lacks motion or motive and so, during the month and a half it takes to be read, it risks recreating daily tedium.

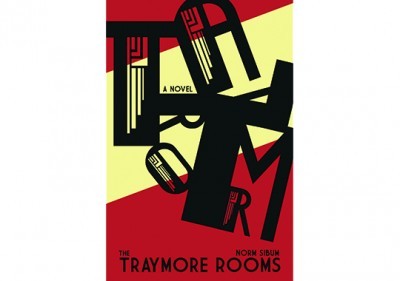

The Traymore Rooms

Norm Sibum

Biblioasis

$24.95

paper

696pp

978-1-92742-822-1

The novel is perhaps attempting to be a literary version of cinéma-vérité – its commitment to the real patterns of language emphasizes authenticity as its guiding value. However, the repetition is often needless: The café is referred to by both its current and previous name, a riff on neighbourhood continuity, but there are only two settings in the novel – the author doesn’t need to remind readers what the café is called every time, nor use both of its names. Q’s crush rolls her eyes up and to the side in almost every interaction. His friend Eggy says “Hoo” hundreds of times – maybe not as bad as it sounds since he always utters it in pairs (“Hoo hoo”). The book faithfully recreates language rhythms, but there are cases where it’s okay to tell rather than show.

The Traymore Rooms feels at times like Sherbrooke Street’s answer to Steinbeck’s Cannery Row, but the work is cluttered with patterns that are more significant to the author than they were to this reader. The nice turns of phrase get lost in the reverb. Sibum picked the cherries and nuts out of life, baked ’em up together with rum and brown sugar, but he needed to offer either more or less of these to get the reading commitment he requests when presenting a 700-page novel.

@RobSherren reviews fiction for the mRb, builds wind farms, and is editing his novel Fastback Barracuda.

0 Comments