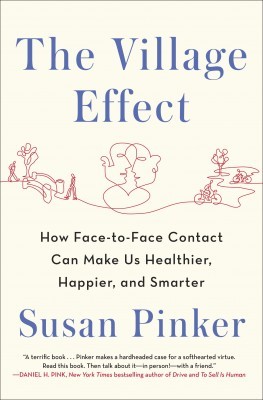

Psychology is something of an anomaly in pop science, inclined as it is to pander to neurotic North American readers hungry for personal solutions. More than a few of its superstar academics are guilty of encouraging the self-help epidemic we’re currently struggling to stave off, and what is occasionally lost in the overzealously prescriptive approach is a scientific appreciation for nuance. Susan Pinker’s The Village Effect: How Face-to-Face Contact Can Make Us Healthier, Happier, and Smarter integrates research about human community and social interaction in a perceptive and timely study. But in Pinker’s impulse to serve readers straightforward prescriptions for this troublesome human condition in which we flail about, she occasionally neglects to balance her thesis with more subtle insights into our minds and bodies.

“Social contact and the drive to belong is a powerful physiological appetite, like hunger,” Pinker argues. A renowned Montreal-based social psychologist, Pinker was awarded the William James Book Award in 2009 for her bestselling title The Sexual Paradox: Men, Women, and the Real Gender Gap. In her new book, she writes that “neglecting to keep in close contact with people who are important to you is at least as dangerous to your health as a pack-a-day cigarette habit, hypertension, or obesity.” According to Pinker, if your spouse is your only confidante – often the case among Americans, apparently – then you are perilously close to having no security at all: “Immunologically speaking, you’re almost naked.”

The Village Effect

How Face-to-Face Contact Can Make Us Healthier, Happier, and Smarter

Susan Pinker

Random House

$32.00

cloth

384pp

978-1-4000-6957-8

I struggle to wrap my head around the implications of what Pinker calls the “Female Effect” – the oft-replicated finding that women’s behaviours spread more readily through their social networks than do men’s. What accounts for this bizarre reality? Pinker has a well-established predilection for distinguishing the sexes neurologically, though it’s a practice I’ve always met with skepticism: where does the “hard-wiring” of gender end and learned behaviour begin? Is the spread of female behaviours simply a result of the biology of human beings who have a surfeit of estrogen coursing through their brains – or is it a cultural thing? These questions go unaddressed.

This skepticism, however, doesn’t take away from the strength of Pinker’s thesis that we silly technology-consumed humans would do well to spend more time with each other in the flesh. The takeaway is that maintaining an integrated social network is currently the single most powerful predictor of a person’s life span. Pinker applies this principle in her own life by consciously pursuing face-to-face social contact every day. She argues that technology, while no doubt a blessing, is also a curse – a false connector that fails to provide the face-to-face rapport our psyches need and a time-sucking device in an already temporally-challenged culture. Among the most convincing arguments, Pinker explores how technology can compromise education. It’s a courageous stance to take in an age when “Educational Technology” is a bona fide college degree, but Pinker’s call to return to the basic values of face-to-face education proves hard to rebut.

It’s unfortunate that Pinker only cursorily acknowledges that people differ in the degree of their need for social contact, and her blanket treatment of the words “happiness” and “health” overlooks what variations on those words might mean. But that’s enough neurotic deconstruction for one day. The Village Effect provides endless fodder for amusing party anecdotes – Strippers earn half as much when menstruating? Some parents in China pay teachers to hug their children? – so quit analyzing and get thee to a party, friends. It’s good for you. mRb

0 Comments