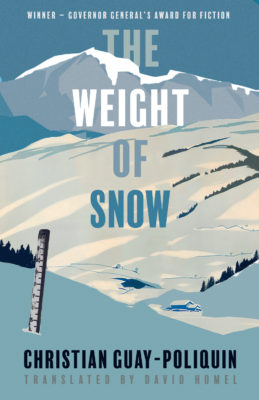

Christian Guay-Poliquin’s second novel The Weight of Snow, winner of the Governor General’s Award as well as three Quebec literary prizes after it was published in French in 2016, has just appeared in English, translated by David Homel. Part dystopian survival tale, part existentialist character study, it’s a compelling read with a minimalist style that masks some heavy-duty themes.

The novel takes place in a northern village during a vaguely defined, possibly apocalyptic scenario in which electricity and communications are permanently down, and the nearest city is under military control. On his return to the village where he grew up, the nameless narrator is seriously injured in a car crash. With nurse Maria, the town’s only medical caregiver, overwhelmed, the village authorities assign an older man, Matthias, to take care of our protagonist during his recovery.

A few other characters float in and out of the story, contextualizing the main narrative with some drama from the village and a few tantalizing details about the overall social break- down. Presumably intentionally, Guay-Poliquin makes the men nearly interchangeable with their very similar names (Joseph, Jonas, José); Maria, the only female character, has a saintly aura befitting her name.

The Weight of Snow

Christian Guay-Poliquin

Translated by David Homel

Talonbooks

$19.95

paper

240pp

9781772012224

Fitting the stoicism of the two characters, the language is minimal, at times evoking the style of a hard-boiled detective novel. Guay-Poliquin devotes much space to the description of snow, sometimes with poetic flourishes – “Outside, the snow is reaching hungrily for the earth” – and at other times simply capturing the hopelessly bleak feeling of the dead of winter all too familiar to Montrealers (I found myself relieved to be reading it in the relative comfort of spring).

There are subtle elements of science fiction in the novel’s world, but Guay- Poliquin stops short of painting any kind of big picture, occasionally teasing out a detail only to retreat into the novel’s self-enclosed main setting. Similarly, with its rugged characters taking on the elements, the story at times evokes an old-fashioned wilderness adventure yarn, but the author invariably pulls back just at the point of action. Section breaks alluding to the Icarus myth are sprinkled throughout, hinting at deep mythological underpinnings that are never explicitly fleshed out. While at times frustrating, in the end this “leave ’em wanting more” approach gives a more complete portrait of his setting, a microcosm of the uneasy social atmosphere in which the story is set.

As you read through and begin to realize just how austere the setting and style really are, a kind of claustrophobia sets in, but Guay-Poliquin keeps it engaging – and the brevity of his chapters nicely breaks up what otherwise could have been a slog. Throughout, he offers intriguing hints that he could have painted a much broader canvas or expanded his focus considerably in any number of directions, but simply chose to do less: the mark of a clever writer. It’s not easy to make such a simple story both profound and compulsively readable, but Guay-Poliquin pulls it off in this literary page-turner. mRb

0 Comments