The one thing that stands out when you read Carolyn Marie Souaid’s This Side of Light: Selected Poems (1995-2020) is that she has been resonating for 25 years. Poems from her first collection, Swimming into the Light (1995), have as much power as those from her last collection, The Eleventh Hour (2020). Indeed, she has different concerns, different areas of focus, but the writing is consistent, as is her ability to move – and sometimes unsettle – her reader.

This Side of Light, which includes a selection of poems from each of her seven collections, begins with a useful and complete overview of Souaid’s writing career by Arleen Paré, also an acclaimed poet. Beginning with Souaid’s having been given a diary at the age of six – the catalyst for her writing life – Paré walks us through Souaid’s university studies, her poetic inspirations and influences, and the kind of poetry she writes: “heart-stoppingly intimate and revealing.” She claims, “From the publication of her first collection, she has allowed readers access into the most personal parts of her life, close to the bone, where she holds them… her literary encounter with Charles Bukowski in her twenties gave her the licence she needed to write poems that are not only personal, but are also, appropriately, unabashedly lusty and raw.”

I would agree with this and note, as Paré does, that Souaid is willing to take on the hard topics with a certain fearlessness. Witness specifically her interpretation of the 1970 October Crisis, explored in her second collection, October (1999), and her sensitive exploration of the lives and traditions of Indigenous people in northern Quebec, now a lightning rod subject, in her 2002 collection Snow Formations.

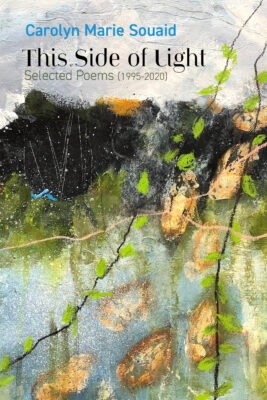

This Side of Light

Selected Poems (1995-2020)

Carolyn Marie Souaid

Signature Editions

$19.95

paper

140pp

9781773241173

The poems from October add a new dimension to any political leanings: with deep compassion, Souaid attempts, in “Last Thoughts of Pierre Laporte, Stuffed and Left in a Car Trunk at St-Hubert Airbase,” to capture the thoughts that might have resided in Laporte’s post-death consciousness following his murder by members of the FLQ. “Thursday Night” explores the far-reaching fingers of political will when a father driving a group of young girls insists “Everybody speaks White in this car!” This calls up the derogatory expression used by English-speaking Canadians towards francophones, cited as far back as 1889 and explored in the 1968 poem “Speak White” by Michèle Lalonde. As an anglophone poet, Souaid is taking on big issues in these poems, demonstrating the fearlessness mentioned earlier.

The poems from Snow Formations, inspired by her time teaching in Northern Quebec, examine Inuit culture and, according to Paré’s introduction, “aspects of colonial culture there” as well as “her emotional, cultural, physical and sexual experiences in the North.” The section’s opening poem, “Sedna, Revised,” introduces the reader to the goddess of the sea and marine animals in Inuit mythology – from Souaid’s viewpoint. “Baggage” considers the lack of words for “forecast” and “certainty” in Inuit culture, while “Dinner at Annie’s” probes the tastes and sounds of this culture with a revelation and respect. This section, the longest in the collection, parses out Souaid’s experiences of snow, sex and death – the “salted particulars” of another life, “the Earth’s exquisite intricacies” that we need to stop and enjoy.

The most powerful poem in the section collecting Satie’s Sad Piano (2005) is the final one, “Letters, 3,” in which Souaid ponders the divinity of menstruation, “the wet knot of heaven between my thighs.” This deep sensuality continues in “Forty Thousand Wishes on Your Birthday,” in the Paper Oranges (2008) section, where Souaid uses words such as “exploded pollen,” “grenadine moon” and “velvet, vulva harps” to explore the intense beauty of female sexuality. And in contrast, in the title poem, Souaid gets philosophical, pondering the what-is-the-point-of-it-all big picture with:

You’re desperate to believe in God

but what inhabits you, locked

behind a chain-link fence

is the blinkety-blank road,

the same slovenly dog

mutating into something bigger

and uglier each day

hoarding the inadequate light.

Souaid is a master at telling us what’s good, what’s different, what’s worthy – but she is also skilled at telling us what is ugly, what keeps us from being better: the pitfalls of human folly. “Scale” from This World We Invented (2005), suggests her goals in more certain terms: “…it’s the layers/ of human thought that append themselves to an idea/ and set its entire life course.”

In this collection, the stand-out piece among so many fine pieces is “The Holocaust Tower,” in which Souaid describes the speaker’s partner losing a pair of glasses while visiting the titular site at Berlin’s Jewish Museum – a site where things are too painfully clear for glasses to even be necessary. When a new pair is procured at the end, we understand all that was truly seen, despite any vision impairment. This is what Souaid excels at: revealing the unavoidable, the inevitable, the ugly – under terms we can accept.

The pieces included from her latest collection, The Eleventh Hour, surf the debt to family that we are always paying – but that we pay with reverence. In “Autobiography,” the speaker imagines her ancestors fleeing Ottoman Turks, their new dawn as “they docked in America” – a homage to their struggles that she might one day honour. In “Timelines,” Souaid takes this yet further, the speaker now paying homage to a father who gave the skin off his back, refuting his own artistic abilities, skimping on electricity so his children could graduate.

But in The Eleventh Hour, Souaid also acknowledges the fierceness of nature, the power of duende within the things we don’t control, the “taking flight along the path of the stars” amid lavender hilltops and chittering birds. For all the ugliness of crashing planes, of war, of pain, Souaid reminds us of the beauty that gets us through.

This Side of Light is a stunning volume of poems that surveys the brilliant career of a Montreal poet. Souaid’s fearlessness is unapologetic, and offers a courageous worldview, one that doesn’t hide from the truth. This frankness, achieved over 25 years, gets new life breathed into it in this curated collection – adorned with cover art fittingly created by Souaid herself. Indeed, in a distinctly tangible way, her fearlessness goes beyond the art of words on the page.mRb

0 Comments