When confronted with trauma, a common contemporary response is “no words.” Yet, “words unspoken fester inside us,” said Goliarda Sapienza, the author of L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy), a novel that depicts a woman unconstrained by conventional feminine roles. Though the book was completed in the late 1970s, it was repeatedly rejected by publishers, only coming to light after Sapienza’s death. Her words on the damage of silence are the perfect epigraph to This Woman’s Work, the raw and powerful graphic narrative by the talented Julie Delporte.

In This Woman’s Work, which exists in the liminal space between autofiction and memoir, Delporte finds the words and draws the images to evoke the struggles of women as they navigate assumptions about gender, femininity, and creativity. The book is both deeply intimate and also emblematic of women who are at a time of crisis, opportunity, and, hopefully, progress.

I met Delporte at her studio in Villeray following a weekend blizzard that meteorologists believe may have been the coldest snowstorm experienced by Montrealers in a century. We chat over a warming pot of tea as snow swirls continuously outside the large windows.

Delporte grew up in Saint-Malo, France, and came to Montreal at eighteen to study journalism and cinema. During a difficult period when reading longer texts was untenable, she immersed herself in comics. “I discovered comics could be literary,” she explains, of finding her métier. I’m particularly interested in her process and ask which comes first, text or image.

“I don’t work in a linear way,” she answers. “My book is a collage.”

The process of creating This Woman’s Work took Delporte four years. Initially, she travelled to Helsinki to focus on the Finnish author and painter Tove Jansson, fascinated with the Moomins – a family of trolls and their friends, some of whom exist beyond gender. Before Delporte encountered Jansson’s work, all her role models were men, she tells me, but Jansson was more than a role model. “I wanted to be her,” Delporte emphasizes. “Historically, there were fewer women doing comics. My book is about finding female role models. I realized I could be a role model, too.”

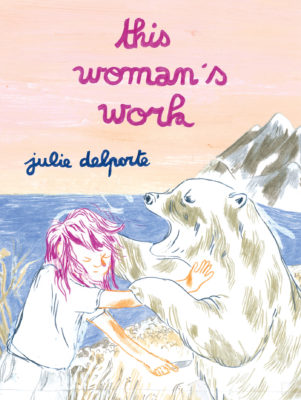

This Woman’s Work

Julie Delporte

Translated by Aleshia Jensen and Helge Dascher

Drawn & Quarterly

$29.95

paper

256pp

9781770463455

The lean, non-linear journal entries juxtaposed with richly detailed coloured pencil drawings are at once fresh and haunting, capable of embodying complex emotions and ideas. The fact that this work is not chronological, and without overt connections between entries and drawings, transports the reader inside Delporte’s mind. As in the best fiction, readers must do the work of interpreting the story.

The narrative opens with a female character engaged in some kind of handiwork, and Delporte tells me she based the drawing on a friend weaving a tapestry. She is facing away from the reader so we cannot see her expression. The text says, “Whenever anything was poorly done, my father would joke: ‘must be a woman’s handiwork.’” And beneath the faceless image, Delporte writes, “Claire, overwhelmed by the immensity of the task ahead.” The narrative then switches into first person as Delporte asks herself, “Why even bother writing this book?”

Delporte is obsessed with women’s bodies: their beauty, but also their objectification. She is troubled by the fact that she will be devalued because her breasts are sagging in her thirties. While swimming naked in a women’s pool in Helsinki, Delporte marvels at a stranger with one breast gliding gracefully through the water and remarks, “who decided that one body is more beautiful than that?”

Struggling to depict her vagina in a variety of drawings that look alternately like a rose, a many-tentacled plant, and a sea creature, Delporte notes that the crux of her problem is that she has lived her whole life without an accurate image of female genitalia.

Though she longs for a child, a girl in particular, Delporte worries about how motherhood will affect her ability to create art, as so many mothers care for a baby solo, while the father is absent or otherwise engaged.

At the core of This Woman’s Work is Delporte’s unburied memory of being sexually abused as a child. “I got my lesson in sex the year I learned to read,” she writes with harrowing directness. The drawing accompanying this entry depicts an outsized wolf with gold, glowing eyes and what looks like a pool of scarlet blood, but on closer inspection, is actually a prostrate little girl. Delporte feels that she is still “carrying the weight of this trauma” and that it is “the story of all women.”

Underlining this theme is the array of female characters who share experiences of sexism. As Delporte writes, “The grammar I was taught still hurts,” because in the French language, the masculine takes precedence.

In This Woman’s Work, there is a palpable tension between inside and outside. While inside, traumatic memories can surface and Delporte may find herself isolated and blocked creatively, even feeling “like an imposter.” But outside she reinhabits herself, as the natural world offers sustenance and strength, whether Delporte is alone or with women friends, whether she is in Finland, France, or Canada. While mushroom picking, she marvels at the pine trees with outward-growing branches and the abundant chanterelles. She loves animals in part because of their “adaptive intelligence.”

When I ask what is up next for her creatively, Delporte tells me about the poetry book illustrated with etchings that she is working on, evolving from her project at Dare-Dare, the artist-run centre located in a construction trailer and dedicated to public art. Entitled Décroissance sexuelle, the exhibit confronts our culture’s attitudes toward sexuality. Each week, Delporte met in a private session with a person who had experienced sexual abuse and they talked and drew together. She also composed one new sentence inspired by the meeting with each person, which were displayed like signage. “I want to put the private conversation about trauma into the public space,” she says. “I’m fed up with dealing with sexual abuse as a solitary, shameful secret. It is so much a part of our culture.”

“As an artist, what are your goals and dreams for the future?” I ask.

“It’s so painful sometimes, making art,” she confides. “The struggle is finding a way to find joy in the process.”

I don’t want to leave yet, but the snow is changing to freezing rain and travel warnings are insistent. Delporte gives me a parting cadeau of a signed, hand-drawn card with an image that looks an awful lot like my Brittany Spaniel, Xeno, whom she hopes to meet. I know our conversation, as well as the one between Delporte and her readers, will continue. mRb

0 Comments