“Daughters, wives, mothers, French Canadians, Roman Catholics, workers.” The millions of women who worked in Quebec’s textile industry for more than a hundred years were sometimes all of these things, sometimes only one. Their bodies were the backbone of Quebec’s industrialization, enlisted in the national project both at home and in the factory. This new study brings them and their voices to light.

Through the Mill: Girls and Women in the Quebec Cotton Textile Industry,1881–1951 focuses on seventy years of women’s work in the textile industry. Structured in two eras (pre- and post- World War I), each era is divided into thematic areas, exploring gender roles, child labour, working conditions, and labour activism over those seven decades. Archival research is punctuated with testimony from a group of eighty-four oral history interviews that Gail Cuthbert Brandt conducted in 1980 with women who worked in the mills as far back as 1906.

In her introduction, Cuthbert Brandt explains that this general-interest book was initially intended for an academic audience. That structure – and, to some extent, tone – has remained, which means the book is exceedingly easy to navigate. It will be a valuable resource for both students learning about early twentieth-century labour history and Quebecers seeking to understand the working world so many of our ancestors participated in.

Through the Mill

Girls and Women in the Quebec Cotton Textile Industry, 1881–1951

Gail Cuthbert Brandt

Baraka Books

$29.95

paper

324pp

9781771861502

Through the Mill comes alive in the moments – unfortunately too rare – where Cuthbert Brandt lets the workers speak. The limited space given to these workers’ voices feels almost old- fashioned, resisting the focus on emotional experience that’s central to most modern oral history. Instead, the interviews are mostly used as fact confirmation. One wishes to have been privy to some of the tangential discussions – about “jam-making, child-rearing practices, and Quebec nationalism” – that she says she had with them. How did these women feel about coming home at the end of a ten-hour shift to face a second shift of domestic labour? We don’t know. The introduction claims to be looking at how these women constructed their identities, but we barely get to meet them.

Even so, a few personalities shine through. Reine says – I can only assume with a laugh – that everyone recognized the night shift spinners because “we were pale, we didn’t have time to see the sun.” There’s a feeling of triumph when, discussing a foreman’s harassment, Zoé declares that, “I told him that if he fired me, I’d smash his face in.” Ten pages about working conditions are brought to life in a few sentences by Flore: “We left [the mill] each day with completely white hair [from the cotton in the air]…. When I arrived home, I wrung out my clothing, winter and summer. I ask myself how it is that we are still alive.”

It’s in those moments that the importance of this book becomes clear, even in its limitations. The women of Through the Mill were long silenced: by their bosses, the Church, and even their families. This study, and their voices, force us to reckon with them not as archetypes but as individuals; not as abstract martyrs, but as clever acrobats, juggling oft-irreconcilable expectations.

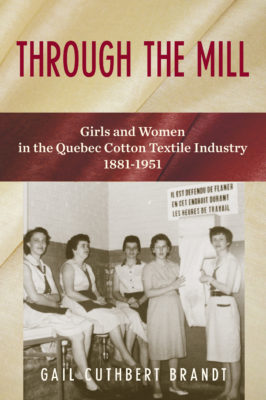

Interspersed throughout the narrative are pictures, some taken by the workers themselves. My favourite is towards the end. Three women sit on the sinks in the factory lavatory; two more stand next to the towel dispenser. Over their heads, a sign: “Il est défendu de flâner en cet endroit durant les heures de travail” (It is forbidden to loiter in this area during work hours). The woman sitting closest to the viewer looks straight into the camera. She smiles. mRb

0 Comments