The Armenian genocide garnered ample press attention at the beginning of 2015. The fervour was not, however, on account of the impending centennial anniversary of the deportation and massacre of approximately 1.5 million Armenians during the Ottoman Empire’s final years; rather, it was due to the involvement in a European Court of Human Rights case of one Amal Clooney, human rights lawyer and wife of George.

Notwithstanding the spotlight Ms. Clooney brings to the case, the timing of Doğu Perinçek’s trial – coinciding with the hundred-year anniversary of the devastating events of 1915 – is poignant to be sure. But beyond easy symbolism, the case against the Turkish politician accused of denying the Armenian genocide is noteworthy for highlighting one of the broader consequences, and enduring dilemmas, of the genocide: What is to be done when a state that perpetrated crimes against humanity refuses to acknowledge the events, let alone take responsibility for them? As the April 24 commemoration approaches, a witches’ brew of domestic and international political machinations, racism, nationalism, and historical revisionism is boiling to the surface. But how is one to make sense of it all?

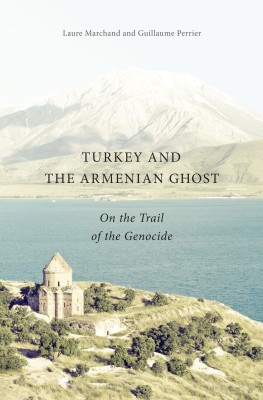

Turkey and the Armenian Ghost

On the Trail of the Genocide

Laure Marchand and Guillaume Perrier

Translated by Debbie Blythe

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$32.95

cloth

232pp

978-0-7735-4549-6

The book pointedly begins not in Turkey but in France, among the sizable Armenian diaspora unofficially headquartered in Marseille. From the outset, the authors’ express interest is in the political and cultural legacies of the genocide, as opposed to the chronology of events (which, they note, is extensively documented elsewhere). “We were there not as archeologists to dig up the past,” they write, “but to learn more about the heirs to the legacy of the genocide and the contemporary manifestations of memory.”

Having originated in a series of previously published articles, Turkey and the Armenian Ghost moves at a clip and switches gears quickly and often, yet it also manages to build a cohesive narrative. Marchand and Perrier showcase an artful and commendable restraint with detail; they clearly draw on a wealth of knowledge, but they don’t make the mistake of attempting to pack everything into these succinct, meticulously curated 200-odd pages.

Organized thematically, the history, interviews, and anecdotes are neatly parcelled out into eighteen short chapters, tackling a wide array of concerns: the diaspora, Turkey’s state-sanctioned “official version of history,” hate speech laws, etc. The most gratifying takeaway for readers – particularly for those who are new to the topic – is the nuanced, multifaceted, and deeply intricate web that the authors have spun, linking the forgotten (or intentionally disappeared) past to the ever-evolving present. Marchand and Perrier’s scrupulous work enables readers, academic and general-interest alike, to contextualize the current contentious debates in Europe.

Regardless of one’s position on whether or not genocide denial should be a punishable crime, Turkey offers perhaps the most compelling argument for such a law; the historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet called it “the very exemplar of a historiography of denial.” As Marchand and Perrier’s text demonstrates, state-propagated historical revisionism, in conjunction with laws that prohibit or severely constrain challenges to that historiography (e.g., Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, criminalizing “denigration of Turkishness”), produces an especially toxic environment for an oppressed minority group whose continued marginalization is directly rooted in that very mythology.

In the words of one survivor, born in 1923, the same year as the Turkish Republic: “Nothing’s finished. The genocide is not over. The state continues to persecute Armenians. And Armenians continue to curse the Turkish government.” mRb

0 Comments