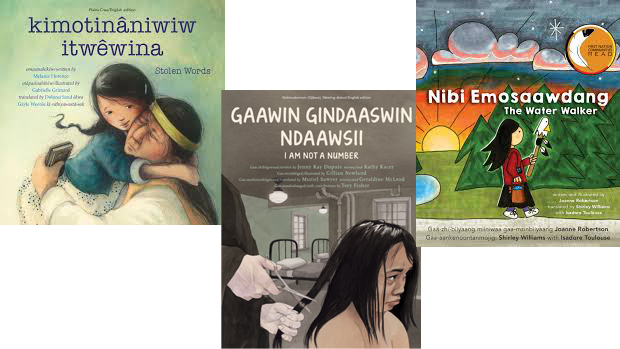

I flip through the pages of three children’s books on my kitchen table. Kimotinâniwiw Itwêwina (Stolen Words) is in néhiyawêwin (y-dialect Plains Cree), Gaawin Gindaaswin Ndaawsii (I Am Not a Number) and Nibi Emosaawdang (The Water Walker) are both in anishnaabemowin (Ojibway). I can only try to explain how amazing it feels for me to write a sentence like that. Or why it’s so important to do so.

Kimotinâniwiw Itwêwina (Stolen Words) is what I call a “wish” story about a young girl who asks her grandfather to say something in their Cree language. He can’t, explaining that teachers at a Prairie residential school had “stolen” it. She decides to help him find his language again with the gift of a found dictionary in Cree.

Gaawin Gindaaswin Ndaawsii (I Am Not a Number) is a true story about a young girl’s experiences at another residential school, this time in Northern Ontario. Jenny Kay Dupuis co-writes this story with Kathy Kacer. Jenny’s Ojibway grandmother, Irene, was eight years old when an Indian agent took her and her two brothers to residential school. They return after a year to their parents with stories of abuse and neglect. Teachers punished them for speaking their language and replaced their names with numbers. Irene’s number was “759.” The parents refused to surrender their children to the Indian agent ever again in this touching tale of resistance and resilience.

Nibi Emosaawdang (The Water Walker) is written by Joanne Robertson. It’s about an Ojibway woman who decided to do something to protect a necessity of life – water. Nokomis Josephine Mandamin sets out on annual walks along streams, rivers, and finally around the Great Lakes to warn people that water – life itself – needs protection from polluters. It’s the story of one woman’s environmental activism and the birth of a political movement.

All three books are examples of a relatively new effort to publish children’s books in dual languages. But the stories they tell are just as important. These are stories about Canada and its history, stories about Indigenous peoples that were buried, suppressed, and denied – but now these stories are finally being told and taught in schools across Canada.

Stores that hit home

Until grade four, I attended the day school at Kanehsatake, near the town of Oka. In all that time, I never saw a word in my own language. In fact, we were punished for speaking Mohawk at school. Like many Indigenous peoples my age, I never learned my own language or my own story. The only book I remember reading at the day school was Fun with Dick and Jane, which was as foreign to me as anything in Mandarin.

I spoke English. With endless repetition, I learned to read “Run Dick run.” I also remember my friends in class laughing at this and other books with their illustrated characters because they looked, dressed, and acted like nothing in our lives. Much later, I learned these books were designed to impress upon our young minds an idealized model that we were expected to adopt so we might assimilate into Canadian society.

Of course, we never could or would because – if we were very lucky – we learned to accept our differences, learn our own history, and be proud of our own heritage. If we weren’t lucky, we lost our identities and wandered without hope as cultural refugees in our own lands.

We had other children’s books at school, of course, but if they portrayed Indigenous peoples at all, they were written, illustrated, and published by people with little or no real knowledge of Indigenous peoples who seemed disinterested in cultural accuracy. Few questioned the familiar colonial myths. Every Canadian child was raised on similar “cowboys and Indians” tropes found in virtually every playground at the time.

Even if there were children’s books that told stories closer to my reality, I doubt we would have been able or allowed to read them in school. But the fact is, books like that just weren’t around. This was a time before terms like multiculturalism or diversity entered public conversation and long before Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission pointed a stern finger at teachers and publishers for excluding Indigenous realities from children’s education:

- Residential Schools constituted an assault on Aboriginal children, families, self-governing Aboriginal nations and culture. The impacts of the Residential School system were immediate, and have been ongoing since the earliest years of the schools.

- Canadians have been denied a full and proper education as to the nature of Aboriginal societies, and the history of the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples.1

Children’s books of the day called Indigenous peoples “Indians” and “Eskimos.” Métis didn’t even appear. We lived in tipis or igloos, rode horses and dogsleds, lived exoticized lives. Colonial myths erased the great diversity of Indigenous languages and cultures and replaced their differences with cartoonish stereotypes. Canadian children’s books portrayed Indigenous peoples more like characters from Disneyland.

A new page

Second Story Press in Toronto published these and other books, written by Indigenous women, in both English and an Indigenous language. Emma Rodgers, manager of marketing and promotions, tells me it seemed a logical if uncertain next step. They had already published Indigenous writers, but only in English. After Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission published its report recommending that books, and especially children’s books, be published in Indigenous languages such as Plains Cree and Ojibway as well, they decided that this dual-language publishing was the right thing. But would it cover costs?

“Initially we thought this would be a small print run, that the majority of readers would be in the (Indigenous) communities where these languages were spoken,” Rodgers explained. “Over the past several years, our sales representatives saw a growing interest among non-Indigenous readers, especially in education and libraries. The further along we got in the process, the more confident we felt there would be a wide audience for these books.”

“We can assume the majority of readers will have no experience with these languages so they will be able to see these printed languages, have a little interaction with them for the very first time,” says Rodgers.

The point is to make Indigenous languages and cultures in Canada, bizarrely, less foreign and more familiar to young readers. It’s part of a global movement to save Indigenous languages from extinction, an effort that’s having a bit of a moment: The United Nations has declared 2019 “the Year of Indigenous Languages.” But part of this means encouraging governments and their agencies to understand that it’s about more than language: it’s about the cultural rights of Indigenous peoples, too.

UNESCO, the UN’s social and cultural arm, says “indigenous peoples are often isolated both politically and socially in the countries they live in, by the geographical location of their communities, their separate histories, cultures, languages and traditions. And yet, they are not only leaders in protecting the environment, but their languages represent complex systems of knowledge and communication and should be recognized as a strategic national resource for development, peace building and reconciliation.”2

An online search shows that this movement is truly global. Orca Books publishes and distributes books in English and West Coast Indigenous languages in both Canada and the United States. Second Story Press works with Orca to reach American readers with its Indigenous-language titles in states such as North Dakota, Minnesota, and as far away as California. Sari-Sari books in Manila, the Philippines, publishes books in regional Indigenous languages like Cebuan (Cebu), Chavacano (Zamboanga), and Ivatan (Batanes), and these are distributed to readers in Canada and the United States as well.

“The stories are based on core Filipino values,” writes a reviewer for Smart Parenting, a US-based organization, “such as Bayanihan, humor, resilience, and respect for elders. More than just physical books, Sari- Sari Storybooks has put the beating hearts of Filipinos onto its pages.”

What strikes me as amazing, however, is that it’s much more than printing and publishing children’s books in Indigenous languages. It’s that these books are written by Indigenous people, telling their own stories in their own way to teach children about their cultures, values, and other ways of viewing the world. They’ve helped broaden and expand the narrow and monochromatic view of the world that had been taught to every child of my generation.

I wanted to know what other Indigenous readers thought about the books, and if anyone else felt the way I did about them. I spoke to Shirley Williams, one of the anishnaabemowin (Ojibway) translators of Nibi Emosaawdang (The Water Walker). She showed this book to some of the students she works with in Indigenous studies at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario.

“People have told me that this is wonderful,” she says. “This is very good. It’s really needed. PhD students, for instance. People who knew Josephine say the book touched them. She was a well-known person because of her walks around the Great Lakes.”

It’s those personal connections to the stories, written and translated by Indigenous people who knew the writers or shared the same experiences, that makes books like these popular among non-Indigenous readers, too. They certainly speak to me in a way that I can relate to even if I don’t understand Plains Cree or Ojibway.

Maybe they will to you too. mRb

0 Comments