For Montreal writer Chris Bergeron, our city is “a transgender city.” Bergeron is the author of the novel Valid – Valide in its original French version, which has been translated into English by Natalia Hero. “There is a form of non-binariness to Montreal,” Bergeron tells me as we video-chat one afternoon in late summer. “It’s always changing identities and languages – nobody can agree on what Montreal is. It’s a French city, no it’s bilingual; it’s old-timey and racist, no it’s very open-minded and friendly; it’s bad for business, no it’s a tech hub.”

Bergeron herself has lived many lives here over the decades – in the ’90s, she was a nightlife reporter, writing for the now-defunct Chart magazine as well as La Presse, working at CKUT, then eventually moving to Voir, where she stayed for many years. Now a fiction writer, she makes a living working for an ad agency. When she walks around the city, she is aware of the palimpsest of past identities of the buildings she passes – this one used to be a music venue, that one used to be a dive bar. She is perfectly placed to write a book like Valid, a “dystopian autofiction” novel that mines elements of Bergeron’s own past and present in order to project trans lives into an unstable and all-too-familiar-sounding future.

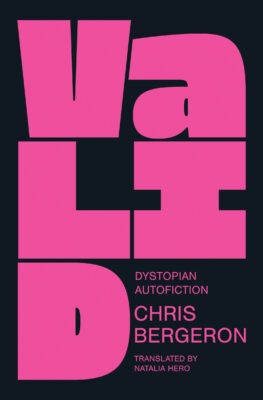

Valid

Chris Bergeron

Translated by Natalia Hero

House of Anansi Press

$22.99

paper

248pp

9781487011130

Valid was also an attempt at exorcism – she hoped that by writing the ominous future that trans people fear, she would be able to ward it off. But unfortunately, even within the time that’s elapsed between Bergeron writing the novel in French and the publication of its English translation, there has been a frightening escalation of anti-trans legislation across the U.S., and recently in Canada as well.

Valid is the story of Christelle, a seventy-year-old trans woman living a materially comfortable, but closeted and isolated, life in a near-future Montreal, whose social, political, and legal structures are controlled by a powerful algorithm called David. Christelle, over the course of a day, tells her life story to a local David network, which has been disconnected from the larger Total David network for a limited time by trans and queer activists. David is a mash-up of Alexa and Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Big Brother: he is in turns obedient and willing to please, and also severe, surveillant, and prohibitive. Hero’s translation is confident for the most part, navigating both Christelle’s human and David’s AI diction smoothly, though occasionally the original French grammatical structures are too apparent.

Bergeron tells me that she wrote David as a clever and therefore sometimes tyrannical child. “But there is no good or evil in David,” she reminds me. “David follows a protocol. The good or the evil of David is what the system, created by people, has decided he will be.” David watches and records; he controls entertainment, archives, architecture, and the police; and he makes sure that anyone not conforming to a productive, cis-heteronormative life is removed from the comfortable city centre, where greenery is abundant and freedom is not.

In the novel’s present, queerness and transness are outlawed: “It’s been years since gay, trans, queer and other folks marched under the rainbow flag … Today you call us ‘the 5%’ and our flag is the colour of fog.” Though Christelle came out as trans in her forties, she has since resumed living as a man, out of fear, and in order to keep the semblance of a peaceful existence. Of course, living as a man is anything but peaceful for her – she reverts to her birth name to escape detection by David, and relates the psychological pain of having to detransition and of being separated from everyone she used to know. Now, along with countless other closeted members of the 5%, she has been tasked by an underground resistance group to narrate her real memories and thoughts to the algorithm, which will then, they hope, crash under the pressure of having to “validate” all of the data at once – data that goes against what it has been programmed to accept.

The relationship between Christelle and David is ambivalent, at least on Christelle’s end. David represents repression, and yet he is the only “person” she can talk to in this bleak future. Bergeron says that in writing Christelle’s isolation, in which the only entity willing to listen to her story is an algorithm, she sought to recreate the loneliness that can come with being an elder trans person, without any in-person community: “You spend a lot of time interacting with machines – hopefully with people behind them. Everyone talks about queer chosen family, but especially for elder trans people, it can be an experience of isolation and years of loneliness.” David, on his end, feeds on the memories and stories of humans like Christelle, in order to learn and grow as an algorithm.

Christelle’s reliance on David means that she is not in the right mind to lead a revolution. Other trans people, many of them from the ballroom scene – which has gone underground – are the ones who plot the rebellion. An old lover of Christelle’s, Yukio, contacts her through a messenger, and Christelle decides to follow their lead and join the movement. “Christelle is a variation of me,” says Bergeron, “and I wasn’t about to write myself as a hero; I was doomed to write myself as a coward.” She wanted to be realistic about her own ways of being, she says, and she also wanted to write against the static notion of the trans woman as “courageous.” Bergeron continues: “I wanted to show a trans person who isn’t an activist, who is just trying to live her life. And then, I wanted to show some of the weaknesses that come from that, from cozying up to power.”

In writing the relationship between Christelle and David, Bergeron was also inspired by the nineteenth-century epistolary novels she grew up reading – novels by writers like Laclos and de Sade in which power hierarchies are laid bare through correspondence between people of different classes. As Christelle narrates her memories to David, the algorithm often interjects with “awful despotic platitudes,” using the banal language of power. But Christelle, finally voicing her own story, is not so easily deterred.

“When you’ve been born as many times as I have, you don’t die so easily,” Christelle tells David. For her part, Bergeron has already added more lives to the world of Valid – the sequel, Vandales, is out in French this November. Meanwhile, a film based on Valide is in its production phase. Bergeron’s dream is to write many more books that take place in the “Validverse,” as she calls it – books that follow other side characters, that take place only in the past, or in the very far-off future – but that are all connected by an overarching trans consciousness.

Bergeron continues to write against the tropes of trans people as “devils or martyrs.” “Where are the real people in that?” she asks. Valid draws a canny portrait of one very real trans woman in a world full of compromise, punctuated by energizing moments of corporate-algorithm-busting truth.mRb

Photo by Cosette

This article paints a vivid picture of Montreal as a city of fluid identities, perfectly mirroring the themes in Bergeron’s Valid. I find it compelling how Bergeron links personal history with broader dystopian fears, showing that for marginalized communities, the “dystopia” isn’t only in the future—it’s lived daily. How does the novel explore this tension between past and imagined futures?