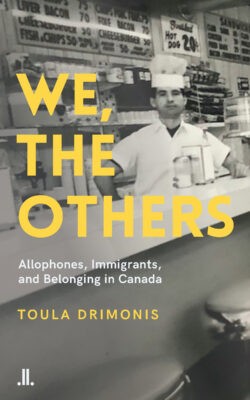

Toula Drimonis is a veteran journalist, freelancer, and opinion columnist whose first book, We, the Others, is a memoir of her parents’ immigration and an exploration of allophone’s political place in Quebec. The book’s purpose is to resist the Coalition Avenir Québéc’s framing of the supposed decline of French in Quebec as a problem caused by immigrants, in which the proposed solution is a vote for the CAQ, reduced immigration, Bill 21, Bill 96, and Quebec’s taking authority over immigration from the federal government. The book begins with descriptions of her parents’ struggles and sacrifices, coming to Canada and settling in Montreal, in order to give readers an emotional connection to her story.

We, the Others Linda Leith Publishing

Allophones, Immigrants, and Belonging in Canada

Toula Drimonis

$22.95

paper

224

9781773901213

Describing these incidents of immigrant groups on equal terms in her book, Drimonis portrays the problem as one of bias, which is a personal attitude, rather than white supremacy, the ideology behind systemic racism, genocidal colonial settlement, and exploitation of resources and labour, which continue today. Not naming white supremacy – by not placing this history in its ideological context – allows those who seek to evoke xenophobic sentiments to hide how dangerous the claim they make is, namely, that immigrants are a threat to the social fabric. As Drimonis knows, electioneering on xenophobia is a tactic of the extreme right across the world. I was disappointed that, while Drimonis appears to be aware of the role of white supremacy in current political discussion, the book presents xenophobia as simply a problem of sentiment. Naming white supremacy need not be an accusation. It’s a call to take up responsibility for one’s role in history.

In the book, Drimonis discusses what she sees as the roots of xenophobia, “Through the prism of Quebec history and nationalism, many Quebecers have somehow managed to divorce French settlement from colonial violence, conquest, and dispossession. Quebec nationalists do not see themselves as being a position of power within the Canadian federation and therefore are never guilty of holding the upper hand in any possible system of discrimination.”

Not only do Quebec nationalists not see themselves as having the upper hand, but Drimonis suggests that they also feel a sense of cultural insecurity. Discussing her book, she tells me, “I do understand linguistic and cultural insecurity. There are legitimate reasons for a lot of that. But a lot of it is so exaggerated and taken out of context. If you get people riled up, if you get people feeling disrespected; these are really easy buttons to push.”

Drimonis is clear about the fact that the CAQ has been drumming up anti-immigration sentiment, for votes. In her columns for Cult MTL, she’s called the tactic a dog-whistle. She writes, “Since its election in 2018, the CAQ has worked hard to play up the need for ‘social cohesion’ by promoting a uniform national agenda and an extremely limited and singular identity that excludes minorities and diverging points of view. This insistence on a singular ethnocentric vision leaves the rest of us with only two options: we either remove all markers of our identity, or we remain excluded. Allophones, through no fault of our own, are the enemy, the ones who dilute French identity”.

Unsurprisingly, Drimonis rejects the CAQ’s xenophobia: “Homogeneity or even consensus cannot be requirements for belonging in a society. We need to leave room for difference and for dissent.”

The later chapters of the book centre on specific media and political controversies over integration. Drimonis reframes these discussions to focus on the feelings of those being told they don’t belong in this society. She also points out that these stories often lack journalistic integrity – one scandal she cites, about Petit Maghreb cafés refusing to serve women, turned out to have no factual basis. “Quebecor doesn’t even care if some of these pundits are literally coming out there and spewing xenophobia and divisive conversation,” she says. “It really deteriorates the social fabric; it’s super negative stuff.”

Drimonis is wary of taking a more confrontational stance, though she sees the connection between Quebec’s colonial mentality and Legault’s xenophobia. When asked about the role of whiteness as a political coalition in the racist and xenophobic events she writes about, she says, “It’s so hard to broach issues of systemic racism and racism and discrimination here, or even Indigenous genocide and everything that took place, with Indigenous communities and Reconciliation. Every time you have these conversations, you constantly get attacked as being a Quebec-basher, and it’s because for so many decades francophone Quebecers have been told that they are this powerless minority. Which they were at some point, and you could say, in some ways, they still are, because they’re still a minority within the majority of Canada, fighting hard to preserve their language and their culture.”

She went on to describe the backlash she receives online. On Twitter, she often discusses interpretations of data on language use, whether Bill 21 infringes on human rights, and other policy questions that are salient to language and immigration laws, with strangers who disagree, not always respectfully. “I get a lot of backlash and it’s consistently the same. It’s always people who will come at you–and I recognize that it’s a small, vocal minority. The average Quebecer is more than capable of understanding the importance of immigration. It’s an open and kind society”.

In the book, she presents alternative views of integration, as, in Legault’s disingenuous words, “une richesse.” We, the Others’ strengths are in Drimonis’ willingness to dive into the history of xenophobia in Canada, and current controversies around immigration and language in Quebec. It is a very necessary, eloquent book, representing the allophone perspective, and an alternative view of immigrants’ contributions to a modern, cosmopolitan society. She defends immigrants, anglophones, and allophones’ right to have political and cultural differences from the white francophone majority.

Immigrants don’t have the opportunity to plead their humanity on an equal basis. In fact, they shouldn’t have to plead their humanity to have a place in this society. We, the Others is a declaration, with evidence, that allophones and immigrants do belong here, coming out in an election cycle that puts that belonging in question.mRb

This book is what is missing from Quebec history specifically, Montréal history .. My opinion; it should be mandatory reading in high school education , used in classrooms to promote safe and intelligent discussions about immigrants and Quebec society .. Thank you to it’s author ; Ms .Drimonis , for having the courage to write this meaningful piece of work !

Our ancestors who came to Quebec as immigrants deserve to be remembered and praised.. and the future generations need to continue their legacy !

in 1953, my Slovene Family immigrated here, via Belgium, where we lived for 5 yrs… My parents chose Quebec, because French was spoken here…. BUT as young children… like all the other immigrants, Caughnawa , included we were NOT allowed to go to French schools… in Lachine, & elsewhere in Quebec… we were called Maudit DP (deported people).. and that is WHY immigrants learned how to Speak English…my parents included…..FYI i did not show my maiden name..since there are only 2 of us in Quebec with that surname…. i used my married name.