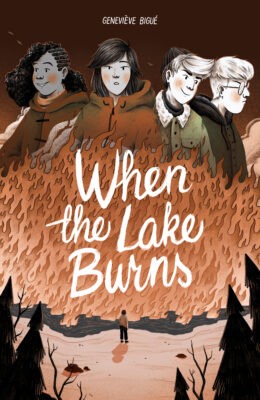

In her first solo-authored graphic novel, When the Lake Burns, illustrator Geneviève Bigué explores the precarity of both our natural and social ecosystems through the eyes of adolescent wonder and curiosity. First published in French as Parfois les lacs brûlent (2022) and translated into English by Luke Langille, the book follows four high school friends in Corbeau River, a fictional village inspired by many real ones in Abitibi-Témiscamingue, the region of northwestern Quebec where Bigué grew up. When news reaches the group that Lake Kijikone is burning, the friends set out to see for themselves and, spurred by teenage fearlessness, to test a local legend: that objects submerged into a burning lake will turn to gold.

When the Lake Burns

Geneviève Bigué

Translated by Luke Langille

Conundrum Press

$25.00

paper

192pp

9781772620979

Bigué reminds the reader of what is at stake in wordless panels dedicated to illustrations of fallen leaves, a single tree branch, or a small group of mushrooms, as the group makes their way through the forest and toward the lake. Her restrained palette of muted greens, greys, and burnt orange comes most alive when the friends leave the uniform village streets and venture into the woods.

The characters don’t dwell on why the fire started; instead, they make bets on whether the legend is true, agreeing that the loser will do the others’ homework for a month. That the cause is left ambiguous reflects the book’s attention to the adolescent perspective. For a moment, through the eyes of the characters, anything seems possible. The cause of the fire doesn’t matter, and consequences are only a vague concept on the horizon.

While the narrative world is imbued with a youthful sense of adventure, Bigué also explores the hard parts of adolescence. Len is somewhat set apart from his friends. Unlike them, he doesn’t have a phone or a bike or a skateboard. He dreams of buying these things with gold if the legend is true, while his friend Theo plans to sacrifice his skateboard to the lake as an experiment. His friends commenting on his trouble spelling English words is a reminder of the importance of language in Abitibi-Témiscamingue, where 95% of the population speaks French as their native tongue. That this dialogue was originally presented in French in Parfois les lacs brûlent calls this context to mind more directly, as well as the unique task of translating a book from French to English in a province where language politics are deeply consequential.

The group’s journey to the lake is a backdrop through which Bigué explores their social ecosystem, which becomes increasingly strained as they move closer (half of the group abandons the plan before they reach their destination). When Len and Theo arrive at the lake, the fun of their adventure melts into a horrifying new reality in the heat of the flames. Balancing fantasy and wonder with anxiety and hardship, Bigué creates a moving portrait of the time when the fearlessness of adolescence is confronted with the heartbreak and struggle of growing up.mRb

0 Comments