Photo: Alan Lissner

Let’s begin with a crucial equation: land theft is the principal issue at the root of Indigenous people’s struggles in Canada, and land retribution is the major solution. Everything else – monetary compensations, land acknowledgements, empty talk about improving the nation-to-nation relationship – is fluff.

As Mohawk activist and artist Katsi’tsakwas Ellen Gabriel tells me in a Zoom interview about When the Pine Needles Fall, her newly published book – co-authored with Sean Carleton, settler scholar of Canadian history and Indigenous studies – anything short of returning the land is an “intentional strategy by government and corporations to continue land dispossession, to tell their constituents that everything has been settled – ‘We don’t know what they [Indigenous communities] are still complaining about.’”

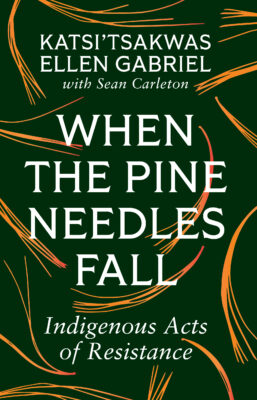

When the Pine Needles Fall

Indigenous Acts of Resistance

Katsi’tsakwas Ellen Gabriel with Sean Carleton

Between the Lines

$32.95

paper

280pp

9781771136501

Which explains why, in March 1990, when the Municipality of Oka decided to allow the expansion of a golf course into sacred Mohawk territory (specifically an ancestral cemetery and a historical place of refuge called “The Pines”), Gabriel and others from the Mohawk community of Kanesatake put their collective foot down, erecting a small and peaceful barricade to stop the developers from defiling their land. What happened next was the gross escalation of events that has come to be widely known as the Oka Crisis, or, as Carleton clarifies in the book, “more correctly, the siege of Kanehsatà:ke and Kahnawà:ke by the Sûreté du Québec (or SQ, the provincial police).”

This included an armed confrontation on July 11, the accidental death of Corporal Marcel Lemay, the Mercier Bridge Blockade, the unbelievable involvement of the Canadian military (who sent 4,500 soldiers, more than were sent at any one time to Kuwait during the Gulf War), and finally, the eventual dismantling of the barricade on September 26, led by the Mohawks and met violently by the army, resulting in (among other acts of brutalization) the stabbing of fourteen-year-old Waneek Horn-Miller. As Gabriel puts it in the book, “all this [i.e., countless acts of violence against Indigenous peoples] for a golf course and condos?”

While Mohawk resistance resulted in an end to the golf course expansion project, and the events of 1990 became an emblem of solidarity and inspiration for Indigenous communities and allies, Gabriel tells Carleton in When the Pine Needles Fall that she sees the outcome of the crisis as a “mixed bag” – for the most part because the “land struggle became lost in the narrative of 1990 Mohawk siege.” Media coverage focused on “images of Mohawk men with masks and weapons facing off against a barrage of Canadian Army personnel.” Land defenders were painted as radical “thugs,” and the “win” that Mohawks achieved did not, it seems, halt the awful march of land dispossession today. The siege was written off as a one-time thing, when actually, as Audra Simpson aptly writes in the book’s afterword, “one might wonder, was that even a crisis at all, or rather a logical manifestation of how things were going – they take, we resist.”

Part of what makes When the Pine Needles Fall resonate so powerfully is that readers can learn about the events of 1990 directly from Gabriel, whose personal involvement as leader in the Mohawk resistance during the crisis was invaluable, and whose vast knowledge and attention to detail is formidable to say the least. The point is to “cut through all the myth and lie,” says Carleton during our interview, “and hear from Ellen directly. In this way we can get to the root of the issue.” Which, it begs repeating, is land dispossession.

But Gabriel does more than just shed light on the events of 1990; she contextualizes the moment within the constellation of history, linking land theft by the Seminary of St. Sulpice in the 1700s to the Oka crisis and the damaging pipeline projects, land grabs, and displacement of today. Colonialism is intersectional; sexist and racist acts of human degradation are enmeshed and inseparable from the pillaging and tarnishing of the earth. She reminds me (resolutely, even via Zoom) that “the whole history of Canada is violent,” that racist pieces of the constitution like the Indian Act continue to exist, and that the earth is still drained and stripped of its resources daily.

Gabriel also alerts readers early on in the book that Indigenous communities will “fight as long as we have to. We’re going to win. There is no other choice but to fight and win our land back.” Further, that a better future is always about living in relation with others, human as well as non. As Simpson writes, “if we are to survive this world, we have to not only live in defiance of colonialism and capitalism. We have to live in a posture of active care for one another.”

It’s fitting, then, that the book opens with a chapter titled “Ohén:ton Karihwatékhwa (The Words That Come Before All Else),” an acknowledgement that is generally used at the beginning of Indigenous meetings, which serve, Gabriel asserts in the chapter, as a “a reminder that we are a part of the natural world, not separate from it.” These words of “gratitude and reciprocity” are woven throughout the conversations and might strike one as a stark departure from the land acknowledgements generally spoken at meetings that take place in settler establishments.

Sean Carleton (photo: Jared Sych)

When we discuss this during our call, Carleton points out that contrary to the “empty and performative” land acknowledgements, “the words that come before all else” explain “the relationship of the collective, which is so different to how settler organization basically acknowledge that they are not indigenous to this land and then move on.” He goes on, “It’s about an entirely different relationship to the land and to the world. Settler governments don’t think about all the relations in the decisions they make. They are just looking for money and power. And that hurts Indigenous people. But it actually hurts everybody and everything. If we can change the way we think about who we are responsible to, that’s a paradigm shift that is beneficial for everyone.”

To get there, Canadians need to know more about the violence of Canada’s history as it pertains to the Indigenous population, and they need to have access to Indigenous knowledge. The way to embark on a new and more relational future is through education and solidarity, and the conversations between Gabriel and Carleton embody both. “This book is an example of a partnership,” Gabriel firmly tells me. “Sean calls himself a settler, but I see him as a friend and colleague.” Not only is When the Pine Needles Fall a behemoth of historical facts and Indigenous knowledge, but it also embodies a friendship, and the care poured into it is certainly felt within its pages.mRb

0 Comments