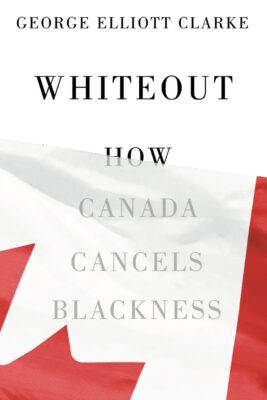

Whiteout anthologizes nearly twenty-five years of selected criticism by George Elliott Clarke, past Parliamentary Poet Laureate and celebrated bard of Afro-Canadiana, on the cultural production of the Afro-diaspora in Canadian history, and its place – or its constant displacement – in national heritage. The essays argue a persistent erasure of over three centuries of Black life and its evidence in Canada.

For Clarke, this erasure is no slip-up, but is symptomatic of this country’s inheritance as European colonies which asserted absolute white domination. One of the few agreements on Canada’s muddled national identity is that Black people are “too polar to the white majority to ever be dubbed ‘Canadian,’” and its institutions act accordingly, through archival neglect or outright annihilation.

Whiteout Véhicule Press

How Canada Cancels Blackness

George Elliott Clarke

$24.95

paper

300pp

9781550656077

The lack of revision, however, in Whiteout’s older essays betrays a disconnection from how the language and visibility of African-Canadian life has transformed in a quarter century, and Clarke’s present-day postscripts are too brief to support how he’s changed with the times. The datedness of his subject matter prepares his pupils for a national context that no longer exists. White supremacy is a term that today appears in CBC headlines and in mandatory HR seminars in the workplace; no longer “seldom heard beyond freak news events of a cross-burning here.” But the essays seem to assume that, for the reader, Canadian anti-Blackness must be a revelation.

I won’t be coy, trying to pull a rabbit everyone can already see out of the hat. Writing “for white people” is perhaps the oldest shame of a Black writer – a claim easily launched but difficult to dispute, or to exactly explain what it entails. It doesn’t, however, inherently detract from writing’s quality or its political service, if it’s clear about its intentions. Clarke is a teacher, after all, and in a nation that relies on systemic forgetfulness as a means of exclusionary violence, informative writing is useful to build political solidarity, which he argues should be a primary goal for African-Canadian communities.

I can understand why: Clarke’s earliest essay dates to 1996, published amid attitudes in the Canadian press, academia, and cultural institutions that fiercely maintained that Black life is rarely sighted in the Great White North. These first audiences were, in fact, mostly white moderates, whether he liked it or not. He has spent much of his career not only helping to found this scholarly field, but defending its once-fledgling existence from eager detractors. A risk of trying to cure racial amnesia is that we can seal ourselves into a cycle of insistent repetition, while time moves on without us.

Whiteout can certainly serve as a time capsule of valuable criticism. Yet the collection also emits a frozenness since the essays, minimally edited for 2023’s readers, retread arguments on African-Canadian presence as if they’re still revelatory. For that reason, it often feels as if Clarke is talking about African-Canadians while talking past them. What could this collection have been if mostly addressed to an audience that already believes him, for whom proof of racist violence is written on their bodies, and who live, each day, the realities that he seeks to theorize? Many of us are already rallied, can already see ourselves clearly: a flourishing African-Canadian literature scene in the last decade says such. What is this Black Canada in need of rescue from “obscurantist insularity” (obscure to whom)? Pull off the cloak. It’s disappeared.mRb

0 Comments