A t age 11, Joseph walks in on his mother being raped and stabs the man to death. In true Oedipal fashion, so begins Against the Wind by Quebec writer Madeleine Gagnon who, one might add, studied psychoanalysis at university.

Romances come and go, and Joseph’s mother is indeed the woman of his life, but the fictional letters and diary entries that make up the bulk of this book are inspired by another of Joseph’s great, if fleeting, loves: a former piano prodigy named Véronique. Joseph meets her when they are both hospitalized in a mental institution where, trying to comfort her, he realizes that “you shouldn’t try to avoid pain or sadness or even stupidity, and not even madness. You [have] to go into them, go all the way through them from beginning to end to have any hope of getting over them.” The thoughts come forth with Véronique in mind, but they capture Joseph’s own journey from committing murder as a child in the 1940s to a more peaceful middle age in the 1970s. This journey has turned him into “an old-fashioned romantic for whom the desire to create and the desire to give oneself to another – and for that giving to be reciprocated – are finally the only true foundations of life.” Joseph moves from one set of extremes to another. Scarred from his early encounter with rape and death, Joseph, now a painter, heals himself with love affairs (the original novel’s subtitle is: “Journal d’un jeune homme amoureux”) and creativity.

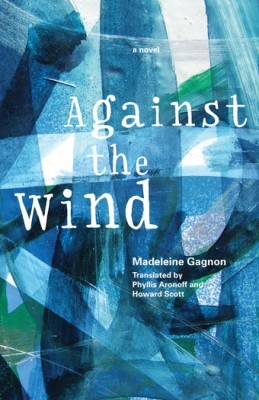

Against the Wind

Madeleine Gagnon

Translated by Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott

Talonbooks

$14.95

paper

159pp

9780889226968

Likewise, Joseph’s story parallels a larger struggle in Quebec during the same period, and the novel shows the most promise with this political parallel, but the glimpses of a Quebec in revolution are largely kept at the level of opaque allegory. Rapes, murders, and mental institutions aside, the plot is mostly preoccupied with the mundane. It recounts the upsets, insecurities, and discoveries of everyday life. Emphasis is not placed on events but rather on Joseph’s inner life. The outlook is small.

Language, and not narrative, is Gagnon’s focus. As a poet, she writes evocative, if at times flowery, lines: “I felt I needed more experience to portray that Beauty that had slipped quietly from the realm of Death into the realm of Life.” She experiments with a mixed bag of styles and moves from the first person to the third person to epistolary prose. She employs various sentence structures and effects.

Such wordplay is difficult for translators. In English, the strict facsimile of some of these effects – the overabundance of quotation marks, for example – conveys little and can be plain annoying. At other moments, liberal translation diffuses meaning. Take the title, for instance: Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott translate Le vent majeur as Against the Wind. The variety of references to wind in the book does not quite render the notion of “against,” which they decided to add.

These problems with language and translation, however, mirror Joseph’s struggle. As he writes his story through diaries and letters, Joseph believes that he’s “speaking these words knowing they’re imprecise. No word in any language will ever convey the full measure of death and loss. No combination of words either. No image or music ever created. Words, images and music are only rituals to ward off the ill fortune of death.” Writing is inadequate as a means of communication, but it is effective as an act of mourning and, ultimately, healing. mRb

0 Comments