In 2011, during the Montreal Jazz Festival, Diana Krall had a solo show. Alone with her grand piano – sans bass, drums, or guitar as backup – she discussed the different songs and musicians that inspired her in her youth and played some of these songs to the attentive audience. It felt as though we were sitting in Krall’s parents’ living room, watching her flip through her dad’s old music sheets, and listening to her revive these old tunes. It was intimate, seemingly spontaneous, and thoroughly enjoyable. The same can be said of Julija Šukys’s second book, Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė.

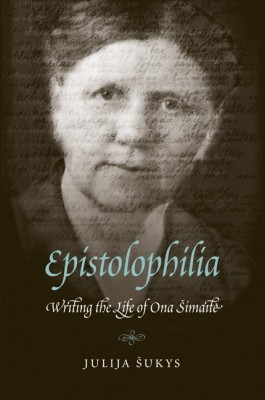

Epistolophilia

Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė

Julija Šukys

University of Nebraska PRess

US $24.95

cloth

217pp

978-0-8032-3632-5

At first I really wanted to write a straight biography, but it didn’t work. Everything I wrote ‘traditionally’ was just flat. One of the reasons for this was that there’s a lot we don’t know in this story, so I had to address silences, the questions we didn’t have the answers to. For example, we don’t know how many people she saved exactly. She never told anybody. And there were problems with the archives themselves. I have this huge collection of letters, but a lot of it is the kind of writing that is repetitive: it talks about everyday activities: floor washing, debts, physical pain – the lives of women. I had to figure out how to tease a story out of this and how to make it readable. I was really quite desperate about it at a certain point.

Luckily, her editor told her to write the book in any way she saw fit. “Essentially, once I started to allow the first-person voice into the text and stopped censoring myself, once I started accepting that a major part of the story was the writing of her life, once I decided that it didn’t have to be chronological, which was incredibly liberating, that’s when the book started to come together.”

At times, Epistolophilia can feel like a stream-of-consciousness biography where Šukys takes you from one facet, or sphere as she calls them, of Šimaitė’s life to the next. We encounter her as the Lithuanian librarian who smuggled letters, documents, and Jews out of the Vilna ghetto; the “criminal” who was arrested, tortured and sent to Dachau; the atheist; the aunt who worried about her schizophrenic niece; the old woman who got up at the crack of dawn to work and write all the letters she promised to write. “The activity of letter writing is deeply, deeply connected to this way of life where she gave herself up to others constantly and in extreme ways.” Šukys says. “Eventually it became a burden, but that’s who she was.”

This way of approaching a biography may be jarring at first, especially for those used to reading straight biographies, but if readers let themselves go and follow the flow of this intimate story, they will find that everything falls into place. “As I work,” Šukys explains, “there are questions that arise and sometimes they’re questions that arise out of my own experience. I tend to follow trajectories and that’s what gave birth to this sort of nodal writing. I also think that other lives were embedded within Šimaitė’s and that each offshoot represents a whole other life story.”

A mosaic of Šimaitė’s life, Epistolophilia enables readers to create a three-dimensional person with the little information available. “All of these spheres were somehow touched by her years in Vilna. Her experience and the decisions she made to save lives somehow came into every one of these spheres, these relationships, whether it was her family correspondence or the postwar letters she was writing to survivors and to the families of survivors.”

Šukys’s great respect for her subject inspires respect for her own book. “When I read [the letters]” Šukys writes, “I feel as though she is speaking to me directly…” And that’s also how readers of Epistolophilia feel, as though Šukys is personally telling us the story of this incredible, and incredibly important, woman over a cup of tea.

0 Comments