In her memoir, In Search of Pure Lust, Lise Weil shares a history of self-discovery, led primarily by her lesbian identity, and paints a constellation lit up by a life lived relationally. Weil’s reflections reminded me of Carol Gilligan, a feminist ethicist and psychologist known for her ethics of care – a theory which argues that moral action ought to be centred around interpersonal relationships. Gilligan identifies three stages of female moral development, with the third stage involving the making of moral choices while considering the effects these choices have on others as well as the self. Instead of seeing actions as right or wrong, women ask, “What does this mean for you and I?” This, Gilligan suggests, and I happen to agree, is a type of behaviour at which women excel. Weil exemplifies these ethics while embracing lesbianism as a uniquely transformative experience – an exhilarating, brave, and feminine life lived relationally – and investigates what love and intimacy mean to her.

Weil comes to redefine her understanding of heartbreak after partaking in a Zen Buddhist retreat where she is humbled to discover the beauty in her perceived turmoil, learning to succumb to the present moment and live in the centre of intimacy. This is a valuable lesson after years of running away from lovers in fear of this intimacy. Local readers will also delight in the joy and freedom Weil discovers in her move to Montreal, where she paints a poetic picture of the city at the peak of its vibrant feminist culture.

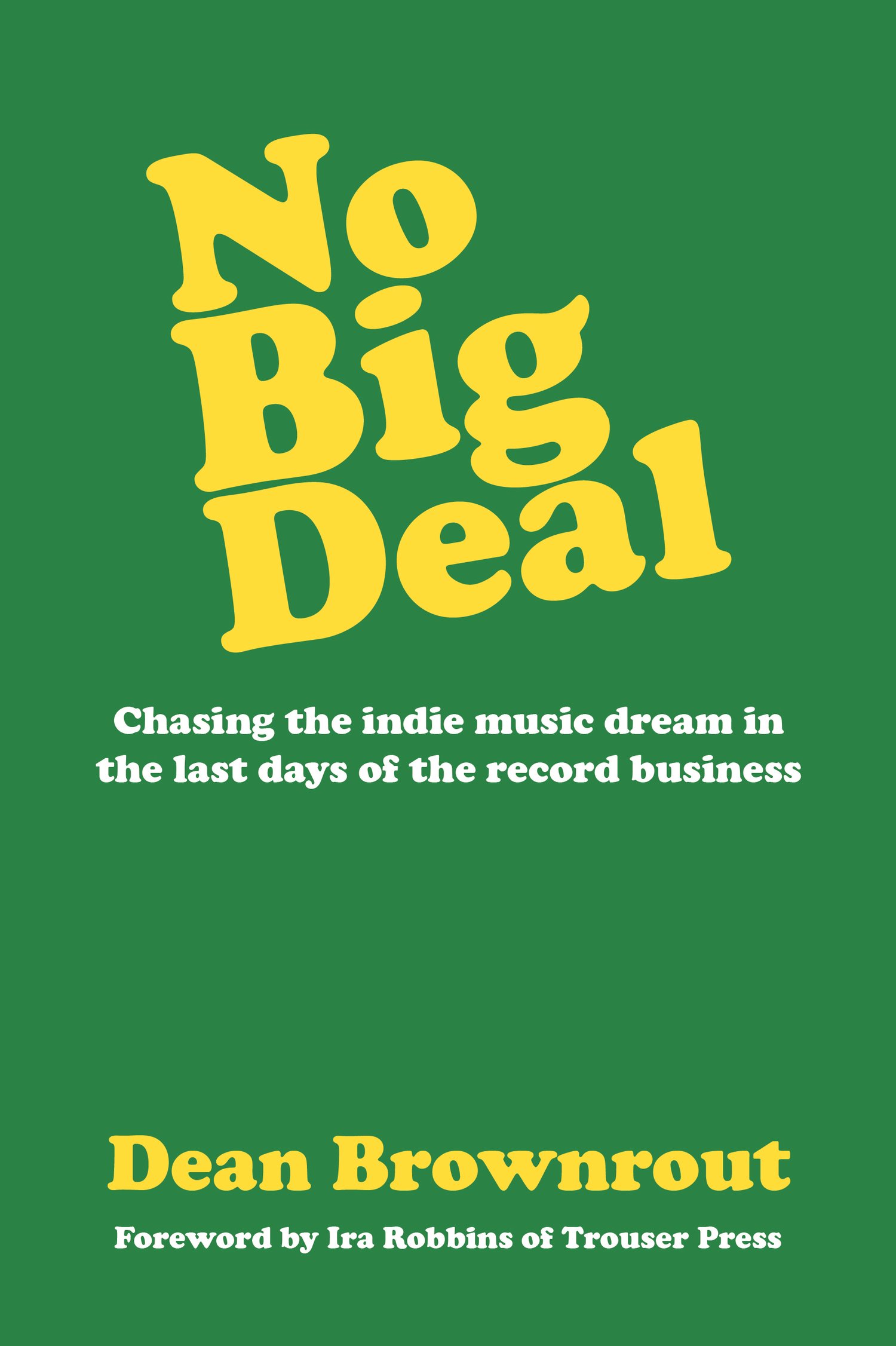

In Search of Pure Lust

A Memoir

Lise Weil

Inanna Publications

$22.95

paper

300pp

9781771334976

Yet the intersection of intellect and matters of the heart quickly proves to be a challenge. Weil finds joy in her collective experience of feminism, often recounting how electrified and inspired she feels after a nourishing group debate. But politics, like relationships, do not function as an autocratic structure – differences are sure to occur. Weil refreshingly makes note of the role of intersectional feminism in the rhetoric of the time, often identifying Audre Lorde as an electric force who continuously brought to light the failures of white feminism. However, these political conflicts shake Weil in all her naiveté and challenges the unifying quality of the politics she initially embraced. Ruptures occur in her female friendships – this, even before love comes to challenge her as well.

Weil finds love in a variety of different women over the course of the book, all of whom thrill her and open her up to expansive new possibilities. She repeatedly speaks of the peak of these relations as “openings” and reveals a tender heart to the reader in the process. This tender heart, however, is only visible to the reader. In her relationships, Weil continuously builds emotional barriers against her various lovers, ultimately pushing everyone away in fear of love. In fact, after presenting a defining lecture at a feminist conference, where Weil states that, “Lesbian is for me as much a moral and political as it is a sexual orientation,” it occurs to her just how far her beliefs have been challenged – in all the relational lessons of her life, both political and personal. How so, the audience asks? “In terms of what is possible between women. Of what is made possible by love and women,” she answers. mRb

0 Comments