Carmine Starnino may be a tough critic, but he’s definitely no “lazy bastard.” I didn’t inquire directly during our recent email interview, but I suspect he’s no nervous Nellie either. How daunting is it to criticize one of CanLit’s stars? I asked instead, referring to his review of Margaret Atwood’s The Door, a particularly feisty piece in his latest collection of critical prose. “At this point, not that daunting. Over the last 15 years, I’ve gone after many of the darlings of Canadian poetry: Tim Lilburn, Susan Musgrave, Christopher Dewdney, Christian Bök, Anne Carson, Michael Ondaatje. These are all poets whose reputations, I argue, depend on an overly enthusiastic, ultimately lazy reading of their work – another kind of lazy bastardism.” (The first kind is explained below.) While admitting he’s “been pilloried for speaking so honestly,” Starnino still believes in “disagreement, debate, controversy,” contending that “a literary scene afraid of these things is not healthy – it promotes lying, dissembling, self-censorship.”

There is nothing slipshod about Starnino’s own relationship to literature. In fact, the very nature – and scope – of his career suggest a tireless penchant for precision. An experienced editor as well as reviewer, in 2011, he left his job as editor-in-chief at Maisonneuve magazine for a senior editor position at Reader’s Digest. Today, he continues on as editor at Signal Editions (the poetry imprint of Véhicule Press), where, in 2005, he published The New Canon: An Anthology of Canadian Poetry.

With his fingers in so many poetic pies, it’s a wonder Starnino also managed to publish four books of his own poetry before the age of 40, the most recent of which, This Way Out (2009), won the A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry and was nominated for a Governor General’s Literary Award.

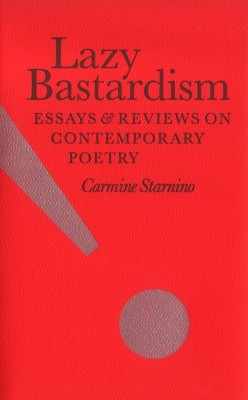

Lazy Bastardism

Essays & Reviews on Contemporary Poetry

Carmine Starnino

Gaspereau Press

$27.95

paper

272pp

9781554471188

Woven throughout his reviews of famous and not-so-famous poets (Starnino has a soft spot for the underdog), are two underlying themes: the status of poetry itself, and the role of criticism in relation to poetry. “And the tradition would not exist – poetry itself would not exist – if those conversations did not happen,” argues Starnino in his prologue, again defending debate.

And yet, as a critic, Starnino has mellowed over the years. Though he can still pack a poetic punch, his latest publication is less aggressive than some of his earlier work. Asked what caused this transition, he replies:

Age. I was younger then, and angrier. I was burning to change everything around me. I’ve since grown older, and realize that it’s harder – and more effective, in terms of the long game – to write essays and reviews that can so persuasively advocate their bias they’re able to change a reader’s mind about a poet, or cause readers to second-guess their assumptions. I now want to be in the persuasion business, not the pissing-off business. Though I do recognize that, sometimes, it’s impossible to do the former without the latter.

Changes in the poetic scenery have also informed the critic’s views. “There’s been a sea change over the last decade toward more formally intelligent, sonorous poetry, something which I tried to track in my anthology The New Canon, ” he emails. “A young poet writing today inhabits a very different context.” Starnino also addresses this shift in Lazy Bastardism, perhaps most notably in his “Steampunk Zone” essay, where he reports “more is going on in Canadian poetry than ever before.”

“More going on” is not to be confused with “more of a market share,” however. In Lazy Bastardism, poetry’s waning popularity is in fact a recurring theme, upon which Starnino elaborates during our interview: “How well does poetry stack up against its competitors – other art forms?” he asks. “The answer is: it doesn’t. Poetry is, at best, seen as a high-prestige niche activity that doesn’t take up any space in the public imagination. Gifted writers who dream of making their mark don’t go into poetry. They become screenwriters or novelists or magazine writers or journalists.”

Starnino doesn’t claim to know all the reasons for poetry’s plunge, though he doesn’t blame the poets themselves. In Lazy Bastardism, he argues: “There is no once-popular style and subject that, if brought back, will stop poetry’s sliding poll numbers.” Nor does he see boosting poetry’s accessibility as the solution. “Poets who … claim to heed the wishes of the common reader out of populist duty, are lazy bastards,” he declares in his opening essay, revealing his title’s intent.

“Contemporary poetry seems afflicted by self-loathing,” he clarifies during our interview. “That’s part of where the lazy bastardism comes from. As poets, we hate what we’re told we’ve become – obscure, difficult, incomprehensible – and some of us turn to the only medicine we believe will lick the problem: anti-intellectualism, fear of elitism, hatred of form. We need poets who recognize, without embarrassment or apology, that poetry is a contrived product, that all of poetry’s ‘instinctive’ properties – sincerity, spontaneity – are fabricated. And we need readers able to admire a poem not only for the seriousness of its content or emotion, but for the achievement of its structure and diction. We have to trust that these readers exist.”

Similarly, in his Eric Ormsby chapter, Starnino claims “A good poet … will help a reader grow up,” and argues: “We are coddled enough by a vapid, linguistically slack media (who have done their part to make us more intimidated, less resourceful readers than we used to be).” And in his review of Jay Parini’s Why Poetry Matters, he contends that poetry critics must also hold the linguistic bar high: “A critic who wants to excite readers about poetry must lead by example …. A critic’s main hold over readers is through words, not ideas. How you say it counts for everything.”

In this regard, Starnino leads well. His own language is typically high-heeled – his essays dressy, like well-tailored suits with sharp linings. Whether or not you share his opinions, it’s hard not to admire his poetic prowess. He requires attentive readers, appreciative of detail, patient enough to peel through layers of intellectual fabric. Stated simply: Starnino does not accommodate lazy bastards.

And what is the purpose of all this toil, one might wonder? Does Starnino wish to win poetry converts? Though he hopes his work will be of use to others, his motives are in fact mainly personal: “I don’t write 5000-word reviews out of some mission, I write them because I can’t help it: I’m driven to do it. I basically write these pieces for myself – to parse my own pleasures and investigate my irritations.”

Pleasure, Starnino later suggests, is also an underlying motive for poets – which might partly explain poetry’s persistence, despite society’s apparent indifference. When I ask about poetry’s purpose, and whether it needs to be rescued, his reply reassures. “What’s the purpose of a sport like hockey or a video game like Halo 3?” he muses, reminding me of the obvious – for poets, there is no such thing as “all work and no play”:

Poetry exists because it gives pleasure to those who write it and those who read it. It exists because whatever you say in a poem sounds better and means more. So poetry isn’t something society “keeps alive.” It’s wired into the very fabric of our language: how we speak and sing. It’s virtually unkillable. As long as words exist, someone somewhere will assemble them into poems. mRb

0 Comments