In #HashtagRelief, Blossom Thom responds to news items on social media. Turning to much publicized violence towards people of colour in recent years, these poems are constructed around figures and events such as filmmaker and activist Bree Newsome and the massacre at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston. #HashtagRelief calls for respite from the barrage of information on social platforms and, ultimately, an end to violence stemming from systemic racism and hate. In “No Justice No Peace,” Thom writes:

Again.

Another bloody body another child dying

…

So tired of untruth.

So tired of vigilantes.

So tired of wrongful deaths.

#Hashtagrelief

Blossom Thom

Gaspereau Press

$4.95

paper

32pp

9781554471720

But the collection is not weighed down by despair. A native of Guyana, Thom projects herself into the future in “Love Letter to the Last Black Man,” and adopts a maternal voice. The poetic missive is instructional, the tone stirring and tenacious:

Your opinion

is worth something and

something more. Raise your voice

my Obsidian King!

#HashtagRelief considers the tweet in relation to grief, the brevity of life, and the limits of language in the face of brutality. At thirty-two pages, this slim chapbook offers a great deal of heft.

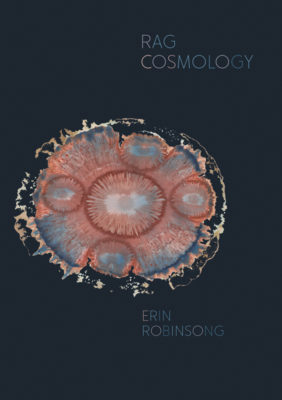

Erin Robinsong’s debut, Rag Cosmology, is a celebration of the natural world, the body, and language. Beginning with Heraclitus’ Fragments (“Souls take pleasure in becoming moist”), Robinsong invites us into a teeming, erotic, and communal world: “look at this brown day / hosted by beauty.”

Rag Cosmology

Erin Robinsong

BookThug

$18.00

paper

104pp

9781771663144

I’m a fold

of it, I’ve never left atmospheric

borders I engorge to the point of

enfolded, I’m a pleat, a pore, a breather, a yellow

drape of it

runs through me violently

Similarly, in “Autobiography,” there is no escape from this condition of rapture. The speaker’s desire is conveyed through nature, punning with the line “pines, firs, yews.” Reminiscent of Susan Howe’s word images, Robinsong subverts the typographical line so the phrase “pine fir yew” is repeated and superimposed. Longing scatters across the paper and touches the division between sense and nonsense, landscape and soulscape:

wood

always

long fir

all

…..ways

bank in,

would always

…..pine fir

…………………….yew

Gratifying and bold, Robinsong’s poems vibrate as the reader is implicated in the lushness of the cosmos, nature, and the self.

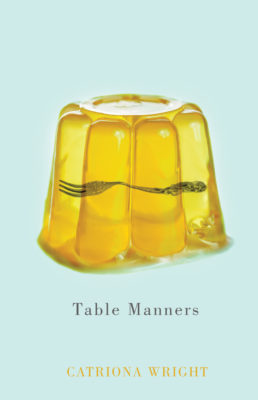

“I’ve been binging / like a magpie, on every glint and texture,” Catriona Wright writes in her epicurean debut, Table Manners. Everything is meaningful as the poet explores the cultural, social, historical, and political facets of food. Ranging from the edible to the inedible, guilty pleasures to all-natural health kicks, dinner parties to lonely meals, Wright uncovers the “glint and texture” of consumption. Her opening poem, “Gastronaut,” is a feast in itself as the speaker reveals the pleasure and intensity with which she hungers, devours, and rejoices in an array of real and imaginary dishes. Gastronomy is a source of joy. No longer mere sustenance, food is a way of being – creative, impossible, rare, and surprising:

My life is now

tuned to bone marrow donuts and chef gossip, I’m useless

at any other frequency.

Table Manners

Catriona Wright

Signal Poetry

$17.95

paper

88pp

9781550654677

Wright reveals how food defines culture, lifestyle, and class difference. Dietary habits, judgement, and expectations are illustrated in poems such as “Groceries,” in which the speaker’s hidden cravings clash with her desire for the cashier’s approval of her health-conscious purchases. Even poems such as “Talking to my Father,” “Lineage,” and “Bridesmaids” show parent-child relationships and female bonds through food. Tightly woven and elaborate in its conceit, the poems in Table Manners linger both on the mind and palate.

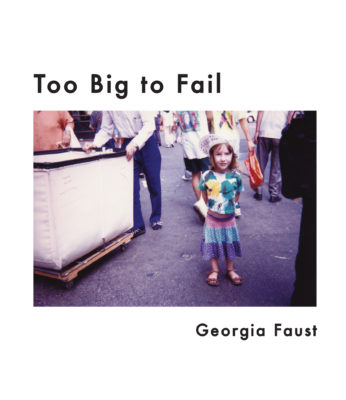

Georgia Faust’s Too Big to Fail is set in American crisis, grit, and debris. Faust transfers the inane capitalist logic behind the phrase “too big to fail” to cultural structures that surround us. As she writes, “[A] sense of disappointment and defeat is the essential state of mind for creative work.” A quick glance at the list of contents reveals a state of demolition: among the titles are “Disaster Event,” “Destruction Architecture,” and “Later Debris.” Embedded in the urban landscape, we find ourselves on the subway, the bus, an elevator, a particular street. We peer through windows, doors, and crevices. But our surroundings are never stable. “Vocabulary controls violence,” she writes, and this sense of violence is both literary and architectural:

Eye contacts speech patterns or

when words form inside the threshold

do I step in new rules to the game.

Too Big to Fail

Georgia Faust

Metatron

$15.00

paper

104pp

9781988355054

In the concluding piece, Faust states, “I am in pursuit of absolute fluency in poetry.” The line recalls the “flow” of an earlier image of the river: “The Mississippi / for example / Goes where it’s supposed to go.” In writing about “the now,” Faust’s words – difficult, estranged, and defamiliarized – reflect a pervasive state of financial and political disaster.

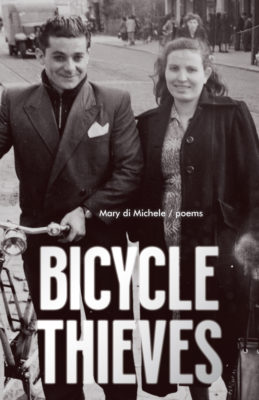

Mary di Michele tells us that “she wants something / that’s gone.” Bicycle Thieves, her latest book, is about precisely this yearning. Imbued with loss and the wisdom of death, di Michele reflects on personal history, immigration, her late parents, and aging. Divided into three sections, she burrows through strata of memories, places, and languages, all the while drawing on literary and cinematic sources. One of the many successes of the collection is how di Michele entwines the personal and the public, exhibiting a private grief that pleads for a witness. Both mourning and reading, as she shows us, are communal acts.

Bicycle Thieves

Mary di Michele

ECW Press

$18.95

paper

96pp

9781770413702

…if I could see

into the darkness and find my father,

if he were still living

……………………………there in Lanciano.…

If I call him

by his true name, Vincenzo, not Vincent,

will he recall then his life in Italian,

through eyes still clear,

……………………………..through hopes undimmed?

Spanning a lifetime, we find consolation in the final image of the father who, in death, rises from his wheelchair in Toronto and finds himself younger, riding his childhood bicycle back in Lanciano.

Bicycle Thieves seeks out what is left after a life is gone. A memory is reduced to a brief sentence, as in the section “Life Sentences.” The dead return unseen, like a cold wind on New Year’s Day. The final section emphasizes this void: “life is a rose – then nothingness.” Di Michele’s voice is intimate and generous, even as her speaker foresees her own future: “The sun was low but I cast no shadow.” These poems contain an insistent beauty that is both sorrowful and exquisite.mRb

0 Comments