The Size of a Bird begins with an imperative. “Write a Place for the Pain” is affirmation as much as it is invocation. The muses being called forth are “the things that didn’t fit into the narrative, that didn’t quite make sense.” Clementine Morrigan continues to write directly about trauma, toxic relationships, sex, queer desire, and the attempt to accept one’s own memories.

Morrigan alternates between forms for each section of the book. The prose sections are immediate, often written in the present tense, and musical. In “Dead Raccoon on the Highway,” they contemplate their body next to another on a park bench and “sounds of shimmering sentences fill the space between silences.” Language hisses; the speaker is distracted by their own mind and the title image interrupts the present moment. This is how time and memory work in The Size of a Bird. The speaker occupies two realities simultaneously. One on the park bench and another in which her “body is not a dead raccoon.” This tension wavers throughout the collection and makes the reader a witness to the ways in which memories cannot be contained by past tense.

The Size Of A Bird

Clementine Morrigan

Inanna Publications

$18.95

paper

102pp

9781771334570

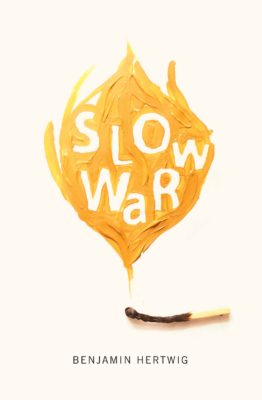

Slow War, Benjamin Hertwig’s debut collection of poetry, addresses the many ways in which war warps youth, hope, and desire. The soldier speaker considers how “war fucks with geography,” which is to say, war fucks with the way we position ourselves in the world. The gaze of the soldier is particular, different from the civilian, or the journalist, or the politician. In this collection, Hertwig remembers, in lyrical detail, moments of violence, fear, and respite. He traces violence from the schoolyard to war, and its aftermath for the soldier.

Slow War

Benjamin Hertwig

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$16.95

paper

134pp

9780773551428

simile and metaphor –

tracks to get around

the fact

that the suicide bomber

was effective

that coyotes eat what they can,

that a man’s head was split

bright like a persimmon and

a foot was resting on the road

like a bird with a broken

…………..wing.

The consequences of the indiscriminate violence of war are made delicate in spite of an uneasiness with making poetry of it.

In “iconoclast,” “the war is over / and we are still // here.” Of course, the war is not over, even if it has been declared as such. This fact is demonstrated in the way the line breaks. Hertwig uses “and” to connect declaratives so there is a moment of stillness, but it is undercut by that devastating “here.” And even if the soldier leaves the front, the war is not over. This is especially true in the last quarter of the book. In “sunday mornings,” the violence of war becomes inseparable from literature:

you start to think: the man in Kafka’s

metamorphosis must have been a soldier with his legs

blown off. how else could he hate himself so much?

(TL)

In Excitement Tax, John Emil Vincent has written a collection of prose poems with complex skeletons, each phrase connected to its context. He manages tone shifts precisely. Poems follow through on such premises as inventing an instrument “inspired by my daycare choir, that sort of presses, almost steps on, children,” dialogue between Walter Wimple Weaselbird (one of the book’s characters) and Socrates, and a child who “never wanted to rehear a single story.”

Excitement Tax

John Emil Vincent

DC Books

$18.95

paper

94pp

9781927599440

“The Wild Hunt” displays Vincent’s skill with mixing registers: “The huntsmen in full cry would set upon any spirits whatever and devour them. And woe unto the living people in the road. It was kind of funny.” Then a “salted, cured human leg” is bestowed upon the “you” of the poem, and the relationship with the leg is lived through. About change, the possibility of abandoning the leg, the narrator says, “it is what makes the world the stinking pile of shit that it is, but you temper your language a bit, since seriously this is your life and your love and your leg.”

Through these tone shifts, seeming non sequiturs, absurd situations, and syntax variation that will hold the interest of anyone who likes being led down the garden path, these poems enact the very excitements and disappointments they describe. (TL)

Bothism is Tanya Evanson’s debut poetry collection, but it is by no means Tanya Evanson’s debut; she has been a cornerstone of the spoken word community for years, a musician, a teacher, and even a whirling dervish. Her background as a performer is evident here – the dynamic wordplay, the dips into concrete poetry, the visual movement in the layout – these poems ache to be read aloud. And yet there is a soft introspection to them; solitude hides in plain sight, but Evanson is never locking us out. Rather, she invites us to the festivities.

Bothism

Tanya Evanson

Ekstasis Editions

$23.95

paper

52pp

9781771712194

Fresh tomato, olive oil, broken bread and Turkish tea beneath the Bozcaada sycamore

Even the deepest losses bring wholeness, a sense of a journey completed or about to begin.

A student of Buddhism and Sufism, Evanson imbues her work with inquisitive spirituality. Whether it’s through literal inquiry, as with “75 Questions,” or an observational visit to a sheikh in Istanbul, she finds a tender playfulness with language that recalls the minimalism of divine texts: “an exit without exit,” and leaves that “drop loud.”

While Bothism is focused on the presentation of contradiction – “the truth and its opposite” – there is no sense of distance between them. Rather than posing contradictions as a way of showing difference, she is posing them as a way of showing harmony, as with “the reverence of abandonment.” Instead of two points on a line, Evanson shows us two points on a circle, and spins us until they come together. (MH)

There is a shimmering layer of violence in Jim Johnstone’s fifth poetry collection that serves as connective tissue for the very dark introspection that occurs throughout. We see this violence in the natural world (“Birds sucked into engines / and gorged by blades”) and used against others:

Glory,

or as near I know it,

is bloodshed

after an attack

The Chemical Life

Jim Johnstone

Signal Editions

$17.95

paper

88pp

9781550654820

That fascination with the self, and the abuses a body can sustain – whether from the world, from mental illness, or from one’s own hand – gives The Chemical Life its hypnotic quality. Bodies are constantly surprising, the impacts of suffering reaching new heights, and all the while “mania splits / the mind’s roof.” The juxtaposition of a body and mind in discord is built into the structure of the book; one’s embodied reality is always in conflict with one’s perceptions. This contrast finds its expression in a “second state,” as shown by the “tinted eye,” or the fish “fighting its reflection / in two- / way glass.”

Johnstone is at his most heartbreaking when he speaks on masculinity and on relationships between men, looking at the emotional distance between fathers and sons, the way they “hardly know each other, have never shown / weakness— not convinced of its existence.” The scorpion’s venom that hides a deeper, more permanent anguish:

If you think I’m ungrateful, try being betrayed

by the orthodoxy, your children……………………………………..and everyone else

………………………….who doubts the scorpion’s malice

After the fact.

The Chemical Life is a painful read, with images so visceral, primal – yet controlled – that they leave us disoriented, seeing double. This bold and self-reflexive collection allows us to experience a personal history as a slow release of pain, felt over the course of a lifetime. (MH) mRb

0 Comments