A Page from the Wonders of Life on Earth

Stephanie Bolster

Brick Books

$19.00

Paper

9781926829708

Wildlife inhabits much of Stephanie Bolster’s A Page from the Wonders of Life on Earth, which meanders through gardens, orchards, museums, and other landscapes to explore how nature is interpreted and transformed through the human gaze. From topiaries to taxidermy, we frame our experiences with nature in order to exert control, impose distance, or make our awe feel somehow more manageable.

Bolster, who co-edited a 2010 anthology of zoo poems entitled Penned, seems to have taken inspiration from that volume. Many of the poems focus on zoos and contemplate how we keep animals in order to keep our own animal nature at arm’s length. “Not me not me not me,” says the zoo-goer in “Hello, You.” And since many of the poems are also about the decline of such places – derelict zoos, neglected urban gardens, a collapsing Crystal Palace – we are often led to wonder what the distance is between a meadow and a lawn? A lion and a house cat? Life and still life?

Although there is an implicit suggestion here that we are nature’s most destructive force, this is not a polemic on our treatment of animals or the environment. Rather, the poems capture and sometimes lament our fascination with the wild and our paradoxical, insatiable desire to tame it. Bolster’s real moments of brilliance are when she seems to suggest that the poem itself is such a process, with the poet ordering the chaos of experience in order to make it seem more meaningful than it really is. Her spare diction and carefully wrought lines are the poetic equivalent of an English garden, with not a blossom out of place. At times the meaning of words is transformed, but methodically, not playfully, as an insect is pinned to a board with its wings unfurled.

The Flower of Youth

Pier Paolo Pasolini Poems

Mary di Michele

ECW Press

$18.95

Paper

96pp

9781770410480

In Mary di Michele’s new collection, an artist comes of age during a time of war. Italian poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini spent World War II in a small village, teaching local boys at a school he ran with his mother. With The Flower of Youth, di Michele at first set out to explore the development of the artist at a tumultuous historical moment, but found that the war was only a distant backdrop for the internal turmoil of a young gay man coming to terms with his sexuality.

Di Michele calls the book “a kind of novel in verse,” perhaps because the arc of the book is more emotional than narrative. Working from Pasolini’s memoirs, she has preserved the limitations of autobiography, focusing on how he judged himself rather than how history has judged him. We discover Pasolini through the countryside he loved (“a grove of acacias to kiss / unseen, safely to kiss.”) and the rural youths after which he lusted, all distilled through di Michele’s lyrical sensibility.

The collection opens with a prologue detailing di Michele’s travel to northern Italy, where she visits Pasolini’s home and grave. The poems that follow, in Pasolini’s voice, explore his life during the war and focus on his passionate encounters with other young men. Those relationships ultimately led to a scandal that forced him to leave the mountain village where the poems are set, but di Michele focuses on the period prior to his discovery, imagining his romantic and sexual desires, and the spiritual anguish they must have inspired in that time and place. “There were / sins I dare not divulge / to this day,” he confesses in “My False Faith,” which explores the collapse of his Catholicism in the face of his budding homosexuality. The book concludes with three translations of a single Pasolini poem in which he imagines the day of his death. Only in the third version does di Michele elaborate on the original enough to hint at the violent nature of Pasolini’s 1975 murder. Indeed, biographical facts are secondary to di Michele’s larger project. Most of the background material comes at the tail end of the collection, in the epilogue. Pasolini is at the centre of the book more as inspiration than subject, a stand-in for the adolescent every-person coming into his own under less than hospitable circumstances.

Li’l Bastard

David McGimpsey

Coach House Books

$17.95

Paper

152pp

9781552452486

Consisting of 128 “chubby sonnets,” David McGimpsey’s latest collection, Li’l Bastard, is what The Dream Songs might have been if John Berryman had been drunk on McDo milkshakes instead of alcohol. Alternately sardonic, silly, and crotchety, these sixteen-line poems are disillusioned but unsentimental pop culture postcards from an avowed but likable bullshitter.

The book chronicles a road trip across North America by a trickster poet in the throes of a mid-life crisis. The speaker of these poems is a tourist/pilgrim in search of a solace that can’t be found on the road, or quite possibly anywhere else. Raging against the indignities of aging, he writes from Nashville, “When I was thirty-five I had a small stroke / and for a brief time dollar signs / appeared to me as question marks — / so I thought you had won the lottery.” The real rage – and punchline – is in the poem’s title: “Song for the Power that Watches over Us and also Reminds Us, from Now On, To Celebrate Milestone Birthdays with a Series of Invasive and Humiliating Medical Exams.” The levity is partly a pose, a lament in funny glasses. Our hero loves, yet seeks deliverance from the vapid flash of pop culture. He walks the Place Versailles shopping centre in east-end Montreal with the same reverence one might feel visiting Versailles itself. “You can’t buy Wrangler jeans at Versailles,” he either complains or boasts.

McGimpsey is the master of effortless irreverence. Where other poets exert themselves looking for ways to innovate, he skewers lyrical earnestness on the one hand and high-brow reinvention of the wheel on the other, while still responding to poetic tradition and forging his own path away from the mainstream. He drives poetry forward by taking the air out of it: “‘Nobody, / not even the rain, has such a hairy back.’”

Echoic Mimic

Lesley Trites

Snare Books

$12.00

Paper

88pp

9780986576522

Also something of a road trip collection, Lesley Trites’ debut, Echoic Mimic, is a “mixed-genre long poem” that follows Ada’s flight from a sleepy hometown and philandering boyfriend to Toronto, where she discovers the bittersweet joys of urban anonymity and the limits of geographic solutions to romantic problems.

Written partly in short lyric verses and partly as a play with dialogue and stage directions, the collection is imaginative and playful in form, and Ada’s ferocity sometimes feels worth applauding: “I will not stick my head in the oven. / I’ll see my poems published before I die.” But Trites’ narrative and language sometimes veer into the too familiar, as when the couple in “Our First Date” exchange an ice cube in an open-mouthed kiss, or Ada lies awake in “Urban Lullaby,” her apartment littered with “unwashed wine glasses / with lipstick imprints / and the grounds / from last Saturday’s coffee.” These feel more like stock images than finely observed details. Such false notes are somewhat fitting for a coming-of-age tale; they can feel a bit like rereading one’s own teenage diaries, filled with over-wrought emotion, unoriginally expressed.

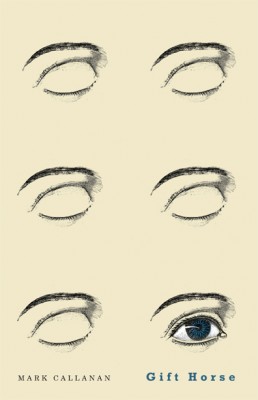

Gift Horse

Mark Callanan

Signal Editions

$18.00

Paper

72pp

9781550653229

It’s a dirty little secret among survivors of plane crashes, shipwrecks, and deadly diseases that life’s fragility, when not a source of wonder, can be the source of some disappointment. After all, survival is really only temporary reprieve, and anyone who lives to tell the tale is starkly aware of the wolves just beyond the forest’s edge. Written largely in the wake of a serious illness, poet Mark Callanan’s second full-length collection, Gift Horse, captures the ambivalence of one delivered from death’s clutches. “There’s something to be said for vetting presents,” he suggests in the title poem, pointing out that the fall of Troy could have been prevented if someone had taken the time to look in the mouth of that well-known horse.

Despite the ambivalence, Callanan doesn’t sound bitter. His poems have the delicate hope and cautious hunger of a convalescent, grateful for the gifts of being, but eager to accept them on his own terms. “These days I would rather haul / myself apart than have it done / without my consent,” declares the speaker of “Butchering Crabs,” which opens the book. Yet for the most part the poems are only obliquely confessional. Callanan’s precision with language and skill with slant rhyme give his poems music, while images of the natural world ground the collection with a bracing chill. Often animals, real or mythical, stand in for the vulnerability, loneliness, or rage of the wounded human. In “Off the Boat,” stowaway rats “risk electrocution / just to raid / the black- ened crumbs / from your toaster tray. / Now tell me / you wouldn’t do the same.” Mortality becomes a bond between the species. The survivor understands why people sometimes act like animals, and why animals act in their own self-interest: life’s brevity is palpable when you know you’re being hunted. mRb

0 Comments