Walter Scott has grown quite attached to Wendy.

You can hear it in the way the cartoonist talks about the artist heroine of his critically acclaimed, cultishly popular series of semi-autobiographical graphic novels, of which the new The Wendy Award is the fourth.

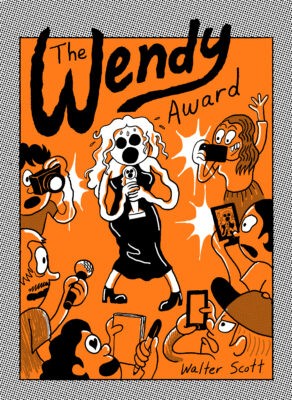

The Wendy Award

Walter Scott

Drawn & Quarterly

$29.95

paper

200pp

9781770467415

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that Scott remembers Wendy’s origin moment clearly and with fondness. It was 2011; the Kahnawá:ke-raised Scott, twenty-six at the time, was a habitué of the Montreal punk scene, a lifestyle that involved a lot of late nights.

“I first drew her on a placemat in a pizza restaurant,” says Scott, “It was in Saint-Henri, across from the IGA on Nôtre-Dame. It’s been replaced by something else since then, like so many other things in Saint-Henri have.”

When the subject of his historical cartooning lineage comes up, Scott heads straight for a bookshelf in his living room and pulls out a volume of Matt Groening’s Life in Hell cartoon series.

“The dry, repetitive, conceptual quality of Groening’s humour is something I was really drawn to as a child,” says Scott, flipping through the book with obvious affection. “He’s not afraid of being dark, and there was no sign of self-awareness that he should be more light. But the subject of influence is interesting, because I don’t actually read a lot of graphic novels. I never have. And I think that’s what has allowed the comic to look the way it does. When I began Wendy, I allowed myself to draw in a crude way.”

That same deceptively simple visual language has occasionally triggered people who are given to saying things like, “My four-year-old can draw better than that!”

“They’re probably right,” Scott deadpans. “Four-year-olds aren’t shackled to the insecurities of adulthood. But I do think I’m better than a four-year-old in every other aspect. And anyway, people who say those sorts of things probably aren’t much interested in art in the first place.”

The new book can stand alone but is probably best read as a continuation of a series that has shone an unsparing light on the contemporary art world. Wendy and a group of fellow artists have been named finalists for a lucrative fictional art prize sponsored by an equally fictional chain called Foodhut. (Their motto: “Because You’ve Got to Eat Sometime.”) The premise is a gateway into a milieu where wildly varying worlds are thrown together, where artists who barely manage to avoid homelessness can end up head-to-head with those who inhabit the international sales stratosphere.

In a trend sure to induce a certain wistfulness in many readers, the new book sees Wendy and longtime best friend Screamo having drifted apart: Wendy is proceeding into adult responsibility and maturity, however fitfully, while Screamo looks to have been left behind. Happily for readers who’ve grown fond of, even protective of him, he finds his way into the new book, albeit in small, self-contained narratives that don’t overlap with the larger plot.

“What’s happened to Wendy and Screamo is something that happens in real life,” says Scott. “But I still want to follow what he’s up to. His life is so different from Wendy’s. She operates in a world of white privilege and pretension, with its own protocol, where he’s navigating this broke, queer, under-represented, druggy world where peoples’ lives are harder and more real. I wanted to maintain that as part of the Wendy-verse.”

It’s been widely assumed that Screamo is named and depicted in honour of the titular figure in Edvard Munch’s 1893 expressionist painting The Scream, but Scott reveals otherwise.

“It’s a comic book series about the art world, so people assume it’s a very direct art reference. I was actually thinking of (Wes Craven’s) Scream films. But so many people have said Screamo comes from Munch that I think I’ll just go with the flow and start telling them they’re right. And I do admire Munch a lot. I’m moved by his unabashed desire to create images of jealousy and rage that are also quite funny.”

A counterintuitive strong point of Scott’s work is its emotional complexity and capacity for delicacy. When it’s suggested that, for all the wild behaviour and dissipation on display, his satire is ultimately rather affectionate and gentle, he agrees. But with a proviso.

“I’ve looked back at a few Wendy stories and been surprised at how angry she allows herself to be,” he says. “It makes me wonder, ‘Does that come from me?’ The line between us gets blurred sometimes. Am I wish-fulfilling through her? Or am I expressing a part of myself that already exists?”

While Scott is at pains to say that The Wendy Award is not a pandemic novel and that he hopes it won’t be received as such, nevertheless there are markers of 2020–22 all through the book: masks, short tempers, contagion paranoia. It’s a reminder of one of the Wendy books’ many layers: its close observation, knife-sharp dialogue, trenchant identity politics, and accretion of detail effectively comprise an ongoing social history. Future generations will get as good an idea of the tenor of North American urban life in the COVID epoch from The Wendy Award as they would from any number of more earnest studies.

Many Wendy fans may be only dimly aware that the books comprise only one part of Scott’s bigger artistic vocation involving many media. While the breadth and variety of that output – encompassing sculpture, installation, and video work, with combinations and permutations thereof – is probably a subject for a different magazine, the question of where it all fits into Scott’s working life leads to a bombshell announcement.

“The pace and the workflow required to make Wendy… it’s demanding,” he says. “I never say never, but my plan is to write another Wendy book in ten years. She will have aged in real time. It’s the only way to write in a way that’s truthful to my experience. Another good reason [for a break] is that I don’t know how accurately I can continue to write a story about a party girl.”

What Scott is saying makes artistic sense. Without giving any spoilers, suffice to say the new book’s conclusion finds Wendy at a crossroads, and she appears to have the wherewithal to make the choices best suited to her self-preservation and general well-being. Probably. It seems only fair to give her the time and space to work out her destiny.

“I do feel her character arc has reached a point where we can put her aside for a while,” says Scott.

In the meantime, will the creator miss his creation?

“Sure, I’ll miss Wendy. But we’ll always have a thread between us.”mRb

0 Comments