MARGARET SANGER: proto-feminist, activist, loudmouth, eugenicist, racist, socialist, visionary, practitioner of free love, founder of Planned Parenthood, pro-lifer, friend to the poor immigrant and to the KKK. Some of this is true, some is half-true, some is straight slander, and all of it is just a Google search away.While Sanger’s name has come to symbolize reproductive justice and early-twentieth-century feminism, lately it has also taken on a darker gloss. She’s been posthumously accused of being a proponent of eugenics and racism, of advocating the forced sterilization of “genetically inferior” citizens, and of trying to decimate the African-American population. Most of these aspersions have been cast by anti-abortion groups who had tried to discredit Planned Parenthood by dragging its founder through the mud (rather ironically, since Sanger herself was pro-life and concentrated her efforts on preventing unwanted pregnancy). But these hatchet jobs only obscure the really troubling parts of Sanger’s era, an era whose ethics she both reflected and transformed.

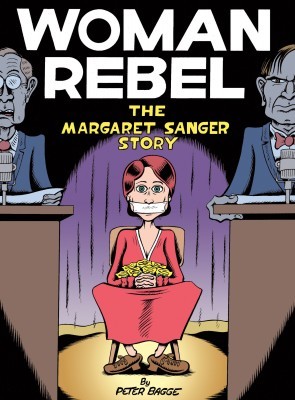

A new cartoon biography of Sanger, written and drawn by underground comics luminary Peter Bagge, attempts to rescue Sanger from the online maelstrom that has her putting the so-called undesirable and unfit under the sterilization knife. Woman Rebel:The Margaret Sanger Story breathlessly takes us from Sanger’s childhood in Corning, New York, to her death at age eighty-six; a mere seventy-two pages covers her activism, advocacy for contraception, run-ins with the law, and various love affairs, in bendy, urgent lines and funny-pages palette. Bagge states in his afterword that he wants to cut through the nonsense that surrounds Sanger to tell the story of a woman who, as he puts it, “lived the lives of ten people.”

Woman Rebel

The Margaret Sanger Story

Peter Bagge

Drawn & Quarterly

$21.95

cloth

80pp

978-1770461260

Bagge’s portrait doesn’t sanctify Sanger, nor does he shy away from her more controversial or unpleasant aspects. Sanger comes off as a bit of a harpy – shrill, single-minded, blind to anything outside her cause. Of course, these are all characteristics that in a male figure would be read as iconoclastic, straight-shooting, visionary. And that’s part of the point – that Sanger took more than her fair share of flak for being a woman, and had to be twice as loud and pushy as male activists to get her point across.

Bagge also tries to contextualize eugenics and Sanger’s involvement, noting in his afterword that it was both a popularly-held viewpoint at the time (and that Sanger’s position was likely less extreme than the majority of its followers) and that it was a response to early- twentieth-century problems the likes of which had never before been seen: overcrowding, rapid industrialization, urbanization. He points out that “eugenics” was not a specific school of thought but rather a blanket term for a variety of practices, many of which we now take for granted, such as contraception and hygiene. It’s not Sanger’s fault, he argues, that today the term evokes forced sterilization and death camps for society’s marginalized people. Bagge’s contextualization shouldn’t be read as an attempt to justify eugenics; nevertheless, the term rankles. It’s basically impossible to try to explain eugenics without sounding like a Nazi apologist, and with good reason.

Bagge only really addresses the eugenics question in the afterword; he’s reluctant to give airtime to the conspiracy theorists and mudslingers, which is fair enough, but a reader who reaches the end of the comic and skips the afterword will be left with a lot of questions. Why, in fact, have the accusations against Sanger gained so much traction? Is it because they feed into liberal guilt, as Bagge suggests? Or is it because we know tacitly that most of our institutions and figureheads are somehow tainted by imperialism and prejudice? Scratch the surface of any do-good organization and you’ll find self-interest and greed. However, that doesn’t mean these organizations don’t do actual good, or that the people who created them were monsters.

Bagge’s biography locates Sanger as a force for change within a rotten system. It doesn’t set her apart from that system. It invites us to think about how we got where we are, and what the people of the future will think of the choices we make today. mRb

0 Comments