Imeet poet Jeramy Dodds on a late summer Sunday morning at Darling, a stylish neo-Viennese café on Saint-Laurent Boulevard. Dodds, who grew up on his family’s farm near Orono, northeast of Toronto, worked as a field archaeologist for a dozen years and attended Trent as an undergraduate before publishing his first book at thirty-four. That book, Crabwise to the Hounds, became a small sensation, winning the Trillium Book Award and landing him on the shortlist of the 2009 Griffin Poetry Prize. With its linguistic flair and serious ideas, Crabwise showed a poet who seemed to have emerged fully formed, capable of almost anything.

Dodds’s poems show flashes of violent action mixed with braggadocious word-shows worthy of Cirque du Soleil – but in person, their creator could not be more different. Calm and courteous, a good listener and thoughtful speaker, Dodds possesses the unhurried manner of one versed in country things, mixed with the precise attention of a graduate student (Dodds earned a master’s degree in medieval Icelandic studies in 2011) and translator of two classics of world literature, The Poetic Edda (2014) and The Prose Edda (forthcoming 2019).

“After Crabwise, I needed time to think about what I wanted out of poetry,” says Dodds. The success of that first book “was kind of like winning the lottery. I was lucky. But if you read about people who win the lottery, it usually ruins their lives . . . people are watching you more, paying attention to you on social media. I can’t say I’ve enjoyed that process.” Translation, he says, was to some extent “a sneaky way to get back to enjoying poetry without the politics.”

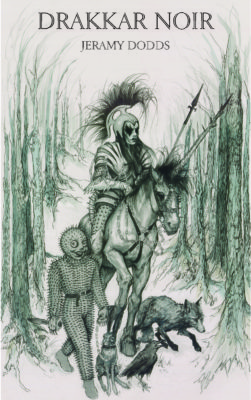

Drakkar Noir

Jeramy Dodds

Coach House Books

$19.95

88pp

paper

9781552453551

The cover image looks like The Wizard of Oz seen through a funhouse mirror, darkly: instead of Dorothy riding the Cowardly Lion, a fearsome Amazonian princess in heavy-metal makeup rides a unicorn warhorse, and the Scarecrow is now an S&M figure in a latex suit holding a chained rabbit in one hand and a dagger in the other. Definitely not Kansas. Inside, one finds decapitated swans, a carport suicide, a child’s hand bitten off by a dolphin, a reappearing psychic stand-in called “my daughter,” and homoerotic buffoons sewn into the corpse of a freshly killed donkey.

“When I was younger, I heard a story, near my hometown, Orono, where two men were ridiculed for being inside a two-man Halloween costume. So I took it one step further,” says Dodds. “If I’m not having fun doing the work, it’s lousy. I try not to be safe. There is a fine line – comedy can go horribly wrong – but talking about yourself is safe, and can never go horribly wrong. Going outside myself was a personal challenge.”

Although it feels more political than his first book, most of the poems in Drakkar Noir aren’t trying to convince the reader to believe this or do that. “Political messages are always very hard on the ears when they’re loud – though I love reading a poem like that when it’s done well. But that’s not the main concern. My main concern is music. How do these words sound next to each other?” Of course, there are pitfalls with this direction, too. Poetry that overvalues sonority and linguistic fireworks to the exclusion of other qualities often lacks the kind of implicit narrative and shades of sincerity that keep readers reading (and caring). A few poems in Drakkar Noir do lose their footing and slide down the ant-lion’s slope toward irrelevancy. But very few. The results in most cases are unique, astounding poems. “Canadæ,” for example, is certain to be an anthology piece for decades to come, and pieces like “Formica Crick,” “Oshawa Shopping Centre,” “Aruba,” “Carport,” “The Oblong Vase,” and “The Swan with Two Necks” are brilliant. Other, more lightly perfumed pieces like “Harbour Porpoise” carry the elegant apprehensions of sadder, more conventional poetry, but in language that never loses its tension:

Suturing the path to where

it was bound, it hung split seconds

in a realm unsoundable by its sonar.

Rural Canada plays a major role in the book, but as with the strangely altered world of the book’s cover, the farmland in Drakkar Noir feels like Robert Frost seen through an unbroken, never-melting pane of ice. In “Long Winter Farm,” the narrator “suction[s] a Baby on Board sign to the rear / window of a hearse” and in “The Wishing Well,” the “badminton handsome” narrator calmly mentions:

Years of tossing

slain calves, tractors, and stillborns down,

and nary a splash was heard.

“To me, rural Canada is the point of view I can speak from,” says Dodds. “It feels authentic for me … I’m not apologizing for being from a hetero white male point of view – I feel that gets checked in the book – but I can’t really write from a different point of view.”

And yet, like many artists, Dodds struggles with the painful chasm between progressive ideals and stubborn human realities. “I worked as an archaeologist for a number of years, predominantly on First Nations sites where it was always unclear which band, which past we were unearthing. White people would come up and ask questions like, ‘Did you find any Indian bones?’ or ‘What do you mean there were Indians here? There have never been Indians here,’ or ‘Are Indians going to come and shut down the town?’ Anger at that ignorance came out in ‘Canadæ.’ Every line I wrote, I felt I was getting angrier with how things are here. How we act like it’s such a great place. We look pretty good compared to the Trump administration, but still, there’s a kind of Tim Horton’s, rural ignorance in Canada that can make one angry . . . The poem became a place to be angry. One time after a reading, a guy said to me, ‘I don’t know whether I want to punch you or hug you.’ I feel the same about the poem and about myself.”

There is, in the end, something enigmatic about Dodds the poet – specifically, the gap between the voice on the page and the author of that voice. Poet-critic Jason Guriel remarked on this quality in Poetry almost a decade ago: “in Dodds’s poems, the pronoun seems both transparent and empty, the sort of sci-fi booth into which anyone could be beamed.” Drakkar Noir carries this anonymity even further, into androgyny: the book’s presiding spirit (and the figure on the cover) is an angry woman. Something about the way Dodds writes creates a breezy, performative space full of great imaginative possibilities and linguistic acuity. If the poet pays for this in self-hatred – the opening and closing poems of the book end in flourishes of self-negation and authorial death – it seems worthwhile for such good results. This book is profoundly refreshing and head-scratching – exactly what brave new art should be. mRb

0 Comments